Reflecting on Lyme disease, 30 years after writing “Dead End Host”

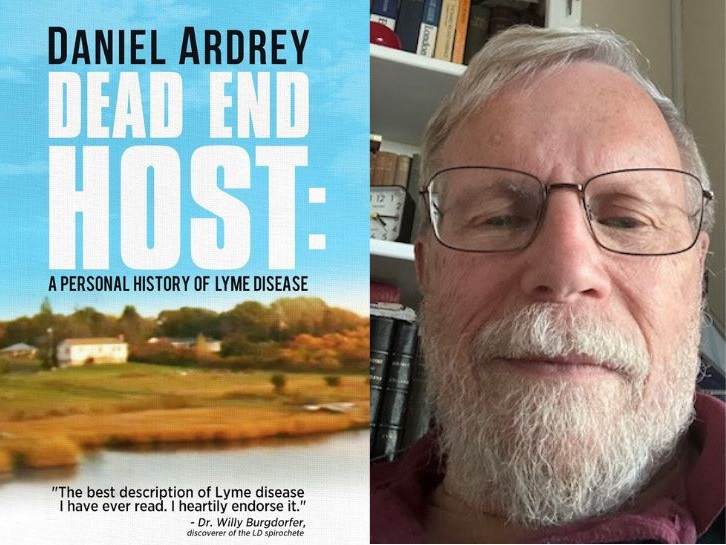

There were few books about Lyme disease when author Danial Ardrey wrote DEAD END HOST in 1996. Now, upon the book’s re-publication, he reflects on his personal experience with the illness and what’s happened since those early days.

By Daniel Ardrey

It’s like another world, going back into it, the world of Lyme disease in the mid-1990s when I wrote my book about it, DEAD END HOST.

I’d gotten sick camping with my young family in New York’s Hudson River Valley, in August of 1991. As is typical with Lyme, this was a sickness of many strange symptoms – especially in my case vertigo, exhaustion, paresthesia (tingling), and diarrhea – in the fall when I was traveling by myself in Europe.

Over the next two years, before I got treated intravenously in the spring of 1993, I had the typical Lyme experience, as described in detail in the book, which I came to think of as medical journey where the patient didn’t go anywhere, the doctors didn’t really believe him, and he had to find his way through the good will and lives of other sick patients.

In rereading DEAD END HOST, I’m struck by how many newsletters from this era I quoted from, including patients from all over the country, their experiences, their symptoms and their insights. They go back in time to the 1960s and reach west to California, up to the Midwest, especially Wisconsin, and south to the Ozarks, Tennessee and along the Mississippi river, and a small town on it, Cape Girardeau, Missouri.

Wide geographical range

In no way is Lyme only a disease of the Northeast, as it was originally proclaimed. In retrospect, this range in geography and time is invaluable, because the newsletters have vanished, but the issues in the patients’ lives are as vivid as ever. Medical papers go into medical journals, many of which I consulted later in the book, but newsletters can simply disappear.

In my life, in 1991-1992, there were the usual “Lyme” suspects, including MS and a spinal tap (which gave me the worst migraine of my life, and I’d had many). I got saved in the end by a doctor who had the guts to treat me intravenously for three months with ceftriaxone against the advice of his colleagues in Boston.

I got better erratically over the next few years, while at the same time I discovered through contacts and medical research at Harvard’s Countway Library that Lyme disease wasn’t what it was supposed to be.

It wasn’t easily curable and could even be fatal. It had a long history in the rest of the world under other names, and there were other similar diseases that were hard to treat and diagnose. The organism that caused it was discovered in the early 1980s by the Swiss tick specialist Willy Burgdorfer, and it was named after him, Borrelia burgdorferi.

Since then, many other similar pathogens have been discovered in a range of ticks, which has added to the medical complexity of Lyme and made life more difficult for the patients.

The nether world of Lyme

Along the way – I’m now 77 and I was 44 in 1991 – I’ve made many fascinating friends in what I think of as the “nether world of Lyme,” and I’ve lost a few as well.

One reason I think the disease can be fatal is because of what happened to my friend Ron Ferris, whom I write about in the book. Ron lived in Calgary and got sick in the 1980s. Eventually, he was diagnosed with relapsing fever (also a Borrelia and carried by ticks) and treated by the path-breaking doctor, Paul Lavoie, in San Francisco, who subsequently died of cancer.

Ron and I were often in touch during the early 2000s – long after my book was written, so this part isn’t in it – and then, out of the blue, I got a letter from his sister saying he had died.

It was the way he died that told me it could be Lyme or a related spirochete. She described a month in the hospital, and nothing could be diagnosed to explain his eventual system failure and death. His body had simply shut down. I don’t have his medical records. I can’t prove a thing.

Invisible tracks

But many of the tracks of Lyme disease are invisible, as recounted in detail in DEAD END HOST. Willy Burgdorfer knew this, and that’s why he described my book as the best book on Lyme disease he’d ever read. God bless him.

He lived to age 89 in Hamilton, Montana, where the NIH lab for tick-borne diseases was located. Why? Because this was where Rocky Mountain spotted fever was most prevalent (also carried by a tick). He was there studying it when Lyme disease showed up to become the next tick-borne pathogen that turned out to be truly dangerous, worldwide, and a voice from the past.

It was a Borrelia, an organism nobody had studied much, that was hard to culture, hard to diagnose, and turned out to be even harder to treat. It was also neurotropic, meaning it was attracted to nervous tissue. This explained some of the weird nervous system symptoms afflicting many Lyme patients.

Going back into the history of similar diseases like relapsing fever (also caused by a Borrelia, carried by ticks and lice, and epidemic during the unsanitary conditions of wartime) and syphilis, I explored in an appendix to the book the similarities and differences between syphilis and Lyme disease.

So it continues

When I talked recently to my friend, Dr. Ken Liegner, who has treated many patients that other doctors had turned away, we spoke of how the Lyme disease controversy has continued.

In his book IN THE CRUCIBLE OF CHRONIC LYME DISEASE, Dr. Liegner reproduced many of the documents from the 1990s and subsequent decades, so readers of DEAD END HOST can turn to him and see how the story continued, as the cast of characters got larger and larger.

Daniel Ardrey lives in Massachusetts. DEAD END HOST: A PERSONAL HISTORY OF LYME DISEASE is available on Amazon as an e-book.

We invite you to comment on our Facebook page.

Visit LymeDisease.org Facebook Page