Previous studies have shown that patients who have persistent or chronic Lyme disease (PLD/ CLD) have a hard time obtaining the medical care they need to get well (Johnson 2011). A new study has found that clinicians who treat this population face significant challenges in providing patients care that is local, timely, and affordable (Johnson 2022).

Between September 23 and December 1, 2021, LymeDisease.org conducted a survey of U.S. clinicians who treat PLD/CLD patients. One hundred and fifty-five clinicians from 30 states responded to the survey and 45 provided comments in the open text survey item. The results of this survey were published this week: Access to Care in Lyme Disease: Clinician Barriers to Providing Care. The primary goal of this survey was to identify the difficulties that clinicians face when caring for patients with PLD/CLD.

We are pleased to present the Clinician Barriers to Providing Care Chartbook summarizing key points from the published study.

Download Your full color

2022 MyLymeData Chart Book

Clinician Barriers to Providing Care: Why Patients Can’t Get the Care They Need

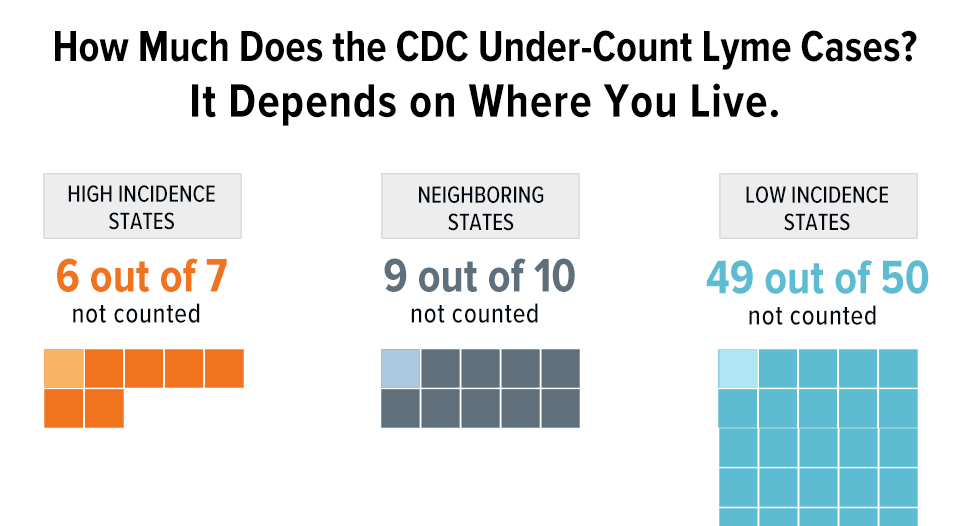

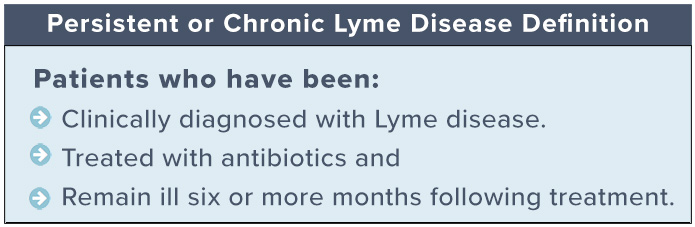

The CDC estimates that 476,000 cases of Lyme disease occur annually (Kugeler 2021). Even when diagnosed and treated early, up to 44% of patients fail treatment, with only 56% considered to have returned to health (Aucott 2022). In later disease, treatment failure rates are higher. Lyme disease patients who remain ill after antibiotic treatment are regarded as having persistent or chronic Lyme disease. These patients may have been diagnosed early or late.

Clinicians who treat PLD/CLD

Clinicians treating patients with PLD/CLD have developed significant clinical expertise. Most clinicians (55%) are medical doctors (MD) or doctors of osteopathy (DO); the remainder are naturopaths with prescription privileges (15%), nurse practitioners (12%) or physician assistants (6%).

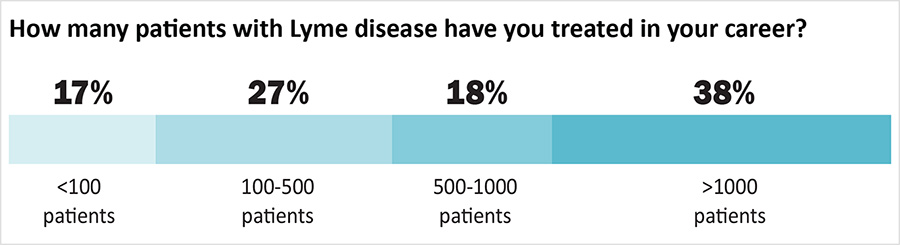

Over half of the clinicians (56%) have treated more than 500 patients and 38% have treated more than 1000 patients. Most (57%) dedicate more than half of their practice treating Lyme disease. Almost all (98%) have taken continued medical education for Lyme disease treatment. Eighty-nine percent belong to the International Lyme and Associated Diseases Society (ILADS) and most belong to other medical societies as well.

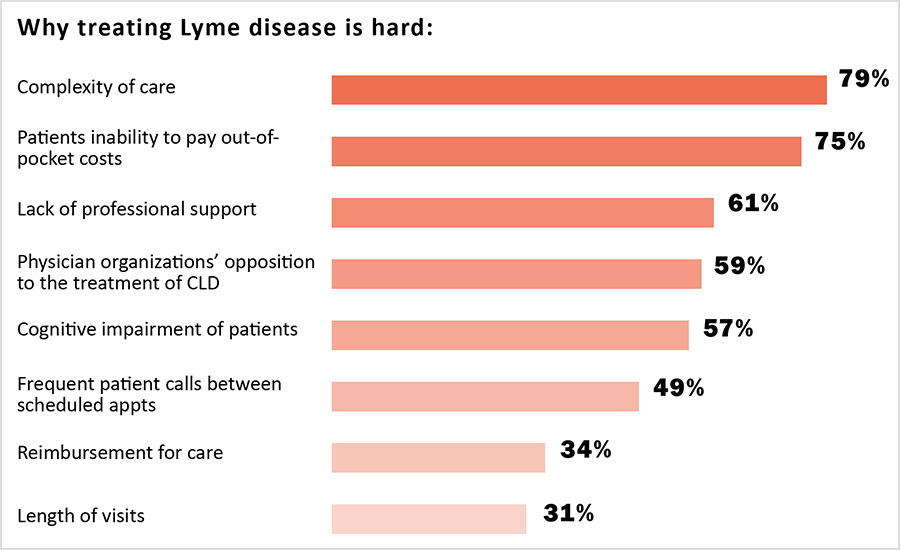

Why Clinicians Who Treat Chronic Lyme Disease Find it Difficult to Provide Care

Despite their considerable expertise, clinicians report that providing care to PLD/CLD patients is challenging. In particular, the complexity of the care provided and the time it takes to provide that care make it difficult for clinicians to provide care using the traditional insurance-based healthcare model. This increases the cost of care provided to patients and makes it difficult for patients to pay for the care that can be given.

The complexity of care needed requires longer clinician visits than treatment for other conditions. For example, 25% of clinicians said their first consultations took more than two hours, and 44% said their follow-up visits took between one and two hours.

Clinicians reported that the length of healthcare visits for PLD/CLD coupled with the additional insurance administrative burdens and reimbursement payment issues make it hard for care to be given under a traditional insurance-based model, which typically relies on clinicians seeing a high volume of patients for short office visits. As one clinician explained:

“The most difficult problem is the cost of providing this amount of complex care on a cash basis. To really review hundreds of records, spend time with the patient and do a proper workup, takes hours. I’d like to see more support for patients and clinicians who choose to help this set of patients.”

As a result of these challenges, most PLD/CLD providers do not accept insurance:

- 74% do not participate in insurance networks

- 76% do not directly bill insurers

- 77% do not participate in Medicare, Medicaid, or other government supported plans

Another reason the insurance model of providing care does not work for PLD/CLD is that the risk of legal or regulatory action by medical boards, insurance companies, and other organizations is heightened for clinicians who accept insurance. Three-quarters of the clinicians who answered the survey say that they have been professionally stigmatized. More than a third (39%) report that they have been threatened with actions by medical boards, insurance companies, or hospital quality improvement committees.

One clinician commented:

“While my patients are generally very supportive, some of my colleagues have stopped speaking to me and I worry about the medico-legal repercussions of what I do.”

Another said:

“I used to practice in a state where physicians who treat complex patients, including people with chronic Lyme, were specifically targeted by health insurance companies for medical board complaints and other attacks ESPECIALLY WHEN THEY HELPED PATIENTS OTHER DOCTORS GAVE UP ON. Eventually I elected to move to [a state] where there is less interruption of care and more protection of vulnerable patients from predatory insurance entities.”

One way clinicians can avoid targeting by insurance companies and other groups is by opting out of insurance networks, Medicare, and Medicaid. Clinicians who are stigmatized or don’t participate in insurance networks have fewer chances to share office space and overhead costs. This increases the cost of providing care. Treating PLD/CLD also imposed additional insurance related burdens that increase the cost of providing care exist even for clinicians who do not participate in insurance networks. These include prior authorization of medications (77%), insurance denials (71%), and other insurance-related problems (49%).

When clinicians do not participate in insurance networks, the economic burden of shouldering the cost of care is shifted to patients. This makes care more expensive for patients who have to pay for care out-of-pocket. It doesn’t come as a surprise then that 75% of clinicians say that a central problem in their practice is the patients’ inability to pay out of pocket costs. One clinician commented:

“I knew that at some point I would be forced to stop taking insurance and move forward on a cash pay only basis. Looking at the numbers, taking commercial insurance for these patients just doesn’t make any sense. I believe that the main issue that causes many of these patients to be without access to care is the amount they need to spend on their practitioners plus the out of pocket costs for out of network testing, labs, and treatment. For most of these patients that is anywhere from $10 to $20K per year. It is a huge burden.”

Essentially, the insurance model of providing healthcare is broken for patients with PLD/CLD. Not only does this increase the costs of providing care for providers and shift the cost burden to patients, it also means that patients can’t get care from their regular provider, must obtain care from places that don’t take their insurance, and need to navigate a complex healthcare maze to even find the care they need. Patient surveys published previously also identify the high cost of out-of-pocket care (Johnson 2011).

In addition, previous surveys have found that patients incur substantial diagnostic delays, misdiagnosis, see many clinicians before being diagnosed, and travel significant distances to receive care (Johnson 2011, 2014, 2020). To obtain care, 49% of patients report traveling more than 50 miles; 31% report traveling 100 miles or more for care (Johnson 2011). Because obtaining care can be expensive, inconvenient, and interfere with work responsibilities, many patients may choose not to get care at all (Johnson 2022).

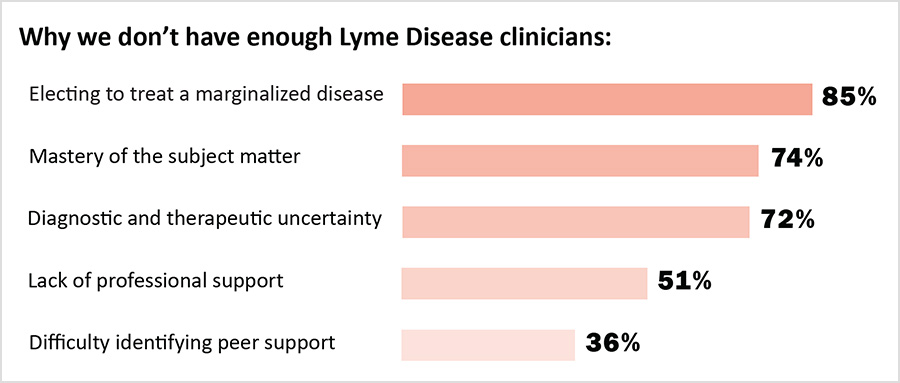

Clinicians here reported that patients with PLD/CLD often had to wait a long time for their first appointments, and that many of their patients traveled from outside their state of practice to obtain care. These factors point to a supply/demand crisis in the treatment of PLD/CLD. There are simply not enough clinicians to supply the amount of care required by patients to get well. The challenges identified by clinicians here—a broken insurance model of care, professional stigma, and heightened liability exposure—also discourage other clinicians from providing care to people with PLD/CLD.

Why Early Diagnosis and Avoiding Misdiagnosis is Important

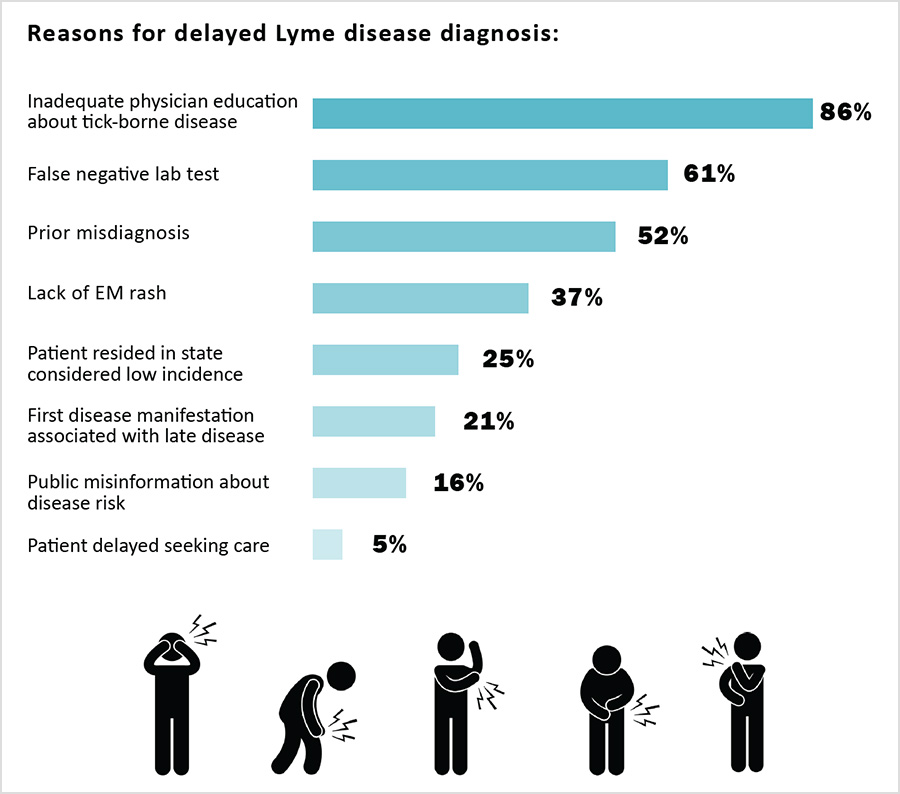

To address the supply/demand crises, it is important to reduce the number of patients who develop PLD/CLD. This requires early diagnosis and treatment. Clinicians identified inadequate physician education about tick borne diseases, false negative lab tests, and misdiagnosis as key causes of delayed diagnosis.

Nearly three quarters of patients report having initially been misdiagnosed. Misdiagnosis is often caused by the lack of education of other clinicians about tick-borne diseases (Johnson 2011, 2018). In a case series of people who might have had early Lyme disease but didn’t have a rash, 54% of Lyme disease patients who didn’t have a rash were given the wrong diagnosis (Aucott 2009). Because of this, misdiagnosis should be seen as a major risk factor for PLD/CLD.

Conclusion

The challenges identified here related to insurance and professional stigma make it hard to keep and hire clinicians who can care for the rapidly growing number of people with PLD/CLD, which is currently estimated to be slightly less than 2 million cases (Delong 2019). They also make care more costly for patients. Diagnostic delays and misdiagnosis increase the number of patients who develop PLD/CLD, exacerbating the supply/demand problem.

As Lyme disease cases rise, the demand for PLD/CLD providers will rise. The limited number of educated practitioners and the expanding number of PLD/CLD patients have created a substantial supply and demand imbalance that must be addressed.

Resolving the supply/demand imbalance is vital for PLD/CLD patients to become healthy. To do this we must:

- improve clinician education to prevent diagnostic delay and misdiagnosis

- retain and recruit more clinicians to address the supply demand crises by reducing professional stigma and recognizing that divergent treatment approaches exist in PLD/CLD

- develop insurance reimbursement models that take into account the complexity of care and the time it takes to provide care.

Failing to address these issues will leave patients unable to access or afford the care that they need.

- Kugeler, K.J.; Schwartz, A.M.; Delorey, M.J.; Mead, P.S.; Hinckley, A.F. Estimating the frequency of Lyme disease diagnoses, United States, 2010–2018. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2021, 27, 616–619.

- Aucott, J.; Morrison, C.; Munoz, B.; Rowe, P.C.; Schwarzwalder, A.; West, S.K. Diagnostic challenges of early Lyme disease: Lessons from a community case series. BMC Infect. Dis 2009, 9, 79. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-9-79 .

- Johnson, L.B.; Maloney, E.L. Access to Care in Lyme Disease: Clinician Barriers to Providing Care. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1882, https://www.mdpi.com/2227-9032/10/10/1882.

- Johnson, L.; Shapiro, M.; Stricker, R.B.; Vendrow, J.; Haddock, J.; Needell, D. Antibiotic treatment response in chronic Lyme disease: Why do some patients improve while others do not? Healthcare 2020, 8, 383. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8040383

- Johnson, L.; Wilcox, S.; Mankoff, J.; Stricker, R.B. Severity of chronic Lyme disease compared to other chronic conditions: A quality of life survey. PeerJ 2014, 2, e322. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.322 .

- Johnson, L.; Aylward, A.; Stricker, R.B. Healthcare access and burden of care for patients with Lyme disease: A large United States survey. Health Policy 2011, 102, 64–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2011.05.007.

- Johnson, L.B.; Maloney, E.L. Access to Care in Lyme Disease: Clinician Barriers to Providing Care. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1882, https://www.mdpi.com/2227-9032/10/10/1882 .

- DeLong, A.; Hsu, M.; Kotsoris, H. Estimation of cumulative number of post-treatment Lyme disease cases in the US, 2016 and 2020. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 352. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6681-9.

If you are a patient who is not enrolled in MyLymeData, please enroll today. If you are a researcher who wants to collaborate with us, please contact me directly.

The MyLymeData Viz Blog is written by Lorraine Johnson, JD, MBA, who is the Chief Executive Officer of LymeDisease.org. You can contact her at lbjohnson@lymedisease.org. On Twitter, follow her @lymepolicywonk.