‘Pandemic’ Asks: Is A Disease That Will Kill Tens Of Millions Coming?

HEALTH NEWS FROM NPR

February 22, 2016

As public health officials struggle to contain the Zika virus, science writer Sonia Shah tells Fresh Air’s Dave Davies that epidemiologists are bracing themselves for what has been called the next “Big One” — a disease that could kill tens of millions of people in the coming years.

Citing a 2006 survey, Shah says, “the majority of … pandemic experts of all kinds, felt that a pandemic that would sicken a billion people, kill 165 million people and cost the global economy about $3 trillion would occur sometime in the next two generations.”

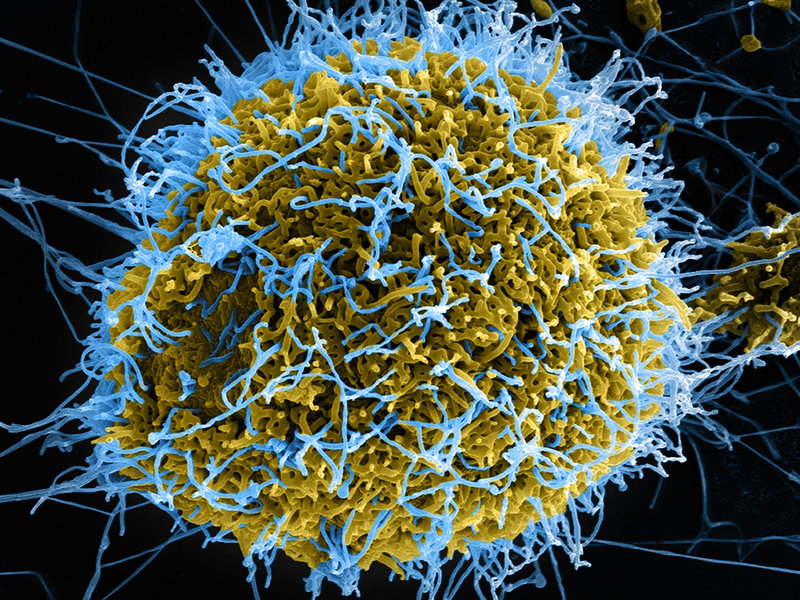

In her new book, Pandemic: Tracking Contagions from Cholera to Ebola and Beyond, Shah discusses the history and science of contagious diseases. She notes that humans put themselves at risk by encroaching on wildlife habitats. “About 60 percent of our new pathogens come from the bodies of animals,” she says.

Shah adds that international travel is also a factor in the spread of disease. “Air travel shapes our epidemics in such a powerful way that scientists can actually predict where and when an epidemic will strike next just by measuring the number of direct flights between infected and uninfected cities,” she says.

Looking toward the future, Shah says that epidemiologists can do more to identify potential outbreaks before they happen. But eliminating them altogether is another matter. “Our relationship to disease and pandemics is really … part of our relationship to the natural world,” she says. “It’s a risk we have to live with.”

On why incidents of Lyme disease are increasing:

Lyme disease is caused by a bacteria that lives in rodents and is spread by ticks. Now in the intact northeastern forest where Lyme disease first emerged, there used to be a diversity of different woodland animals there, like chipmunks and opossums as well as deer and mice and other things, but as we spread our suburbs into the northeastern forest and we kind of broke up that forest into little patchworks, we got rid of a lot of that diversity. We lost chipmunks, we lost opossums, and it turns out that those animals actually control tick populations. The typical opossum destroys about 6,000 ticks a week through grooming, but the typical white-footed mouse, which is what we do have left in those patchwork forests, a typical mouse destroys maybe 50 ticks a week. So the fewer opossums you have and the more mice you have, the more ticks you have and the more likely it becomes that this tick-borne pathogen will spill over into humans. And that’s exactly what happened with Lyme disease and now with many other tick-borne illnesses as well.

We invite you to comment on our Facebook page.

Visit LymeDisease.org Facebook Page