The haunting legacy of Lyme, Connecticut

The ‘Polly Murray Papers’ reveal the horrific symptoms of ground-zero Lyme disease sufferers.

By Kris Newby

Sadness washed over me as I walked through the house in Lyme, Connecticut, where Mary Luckett “Polly” Murray used to live. Built in 1853, it was located in a rural area surrounded by forests, rolling hills, and cranberry bogs. The house needed a fresh coat of paint, and the yard had gone to seed.

The new owner had recently divorced and hadn’t replaced the furniture his ex-wife had taken. There were mattresses on the floor and unfinished projects spilling out of the garage. The owner and his dog seemed unwell. Taking in the scene, I thought, this looks like the flotsam and jetsam of another family destroyed by Lyme disease.

The previous owner, Polly Murray, was an artist, a mother of four sick children, and the disease’s first unofficial epidemiologist. She died in 2019 of Alzheimer’s disease. In the 1960s, she began documenting the bizarre constellation of symptoms that afflicted her family and neighbors living along the Connecticut River. In April, I visited the Medical Historical Library at Yale University to review her original Lyme patient case histories, turning back the pages of time in search of the origins of this mysterious outbreak.

So many questions

These first-hand accounts raised a lot of questions for me. Why did it take 11 years, from 1964 to 1975, for the medical system to take notice and take action?

In 1975, the investigation was assigned to Allen Steere, MD, a young Yale rheumatology fellow who had just returned from a CDC Epidemic Intelligence Service (EIS) assignment in Liberia. Why did Steere narrow the symptomology so soon in the investigation and downplay most of the neurological symptoms? Why did it take six more years to identify the underlying tick-borne bacterium, Borrelia burgdorferi? Did CDC-EIS, the U.S. organization that investigates suspicious disease outbreaks, find it strange that three tick-borne diseases suddenly appeared a few miles from the Plum Island biological weapons lab?

As I looked through the boxes of her notes, I was struck by the unusual nature of the symptoms and the point-source geographic origin. What happened there, and what can we learn from Polly’s eyewitness account?

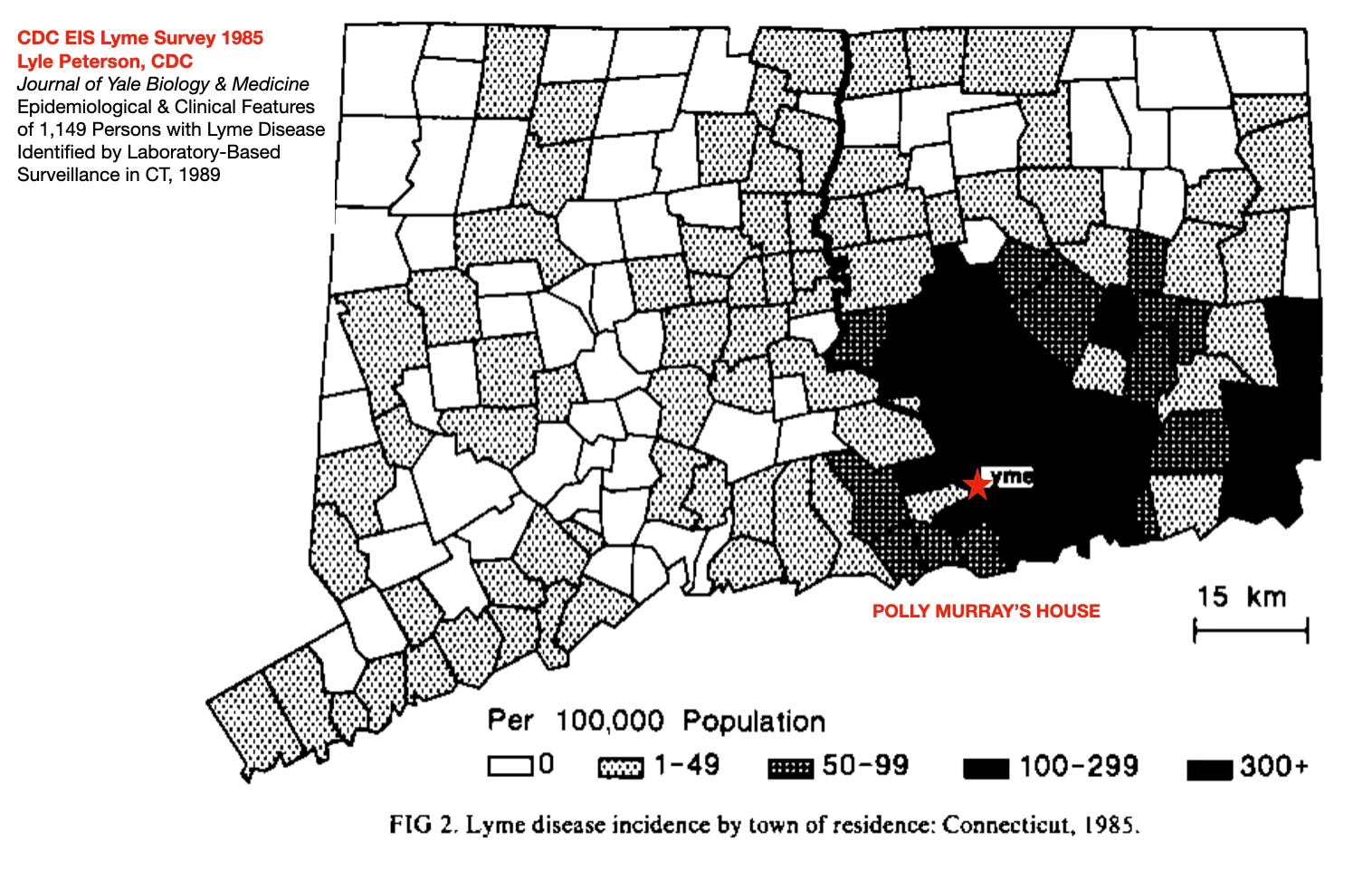

A map from an early survey of Lyme disease in Connecticut, from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control. [1]

Polly’s case histories

Polly’s family had been sick for decades, and the many doctors they visited couldn’t figure out what was wrong—they’d never seen this combination of crazy symptoms before. In a letter to a journalist, she explained why she became the medical scribe for her community:

“Early in the history of our problems, I realized that my only salvation would be in keeping accurate records of what was going on, as unbelievable as it was. I intuitively felt it very important for anyone with baffling chronic symptoms to put the information down on paper.” [2]

Polly Murray, 1954, on graduation day at Mt. Holyoke College, before her strange symptoms began. [3]

Polly filled boxes with notes on her neighbors’ unusual histories, which included relapsing pain, brain fog, mental breakdowns, kids on crutches, children with developmental problems, seizures, lost jobs, broken marriages (including her own), and children too sick to go to school. As a Lyme-area insider, neighbors told her their heartbreaking stories, from personality changes to suicides. Each family’s tragic history read like crib notes for a Stephen King horror novel.

Huge toll of neurological and psychological symptoms

In one list of 35 cases from the 1990s, I was struck by the large number of patients who reported serious neurological and psychological problems. [2] Here’s a sampling:

Patient No. 1.

Diagnosed Lyme disease. Foot problem, arrhythmia, leg weakness.

Neurologist. Lyme encephalitis?

Psychiatric problems. Paranoia.

Hospitalization. Attempted suicide.

Nursing home with weekends home.

Patient No. 2.

Diagnosed Lyme disease. Mental problems. Seen in Boston. Psych tests, Lupus IV treatment. Alzheimer’s? Stroke? Lyme?

Nursing home.

Died 7/1991. No autopsy.

Patient No. 3.

Lyme disease history. Found outside in a nightgown one winter night, disoriented. Nursing home. Positive Lyme titer.

(You can read the complete list here.)

In another document, she noted that 22 of her neighbors had heart issues, 26 had neurological symptoms, seven or more suffered from psychosis or depression, and seven had suicidal ideations. [2]

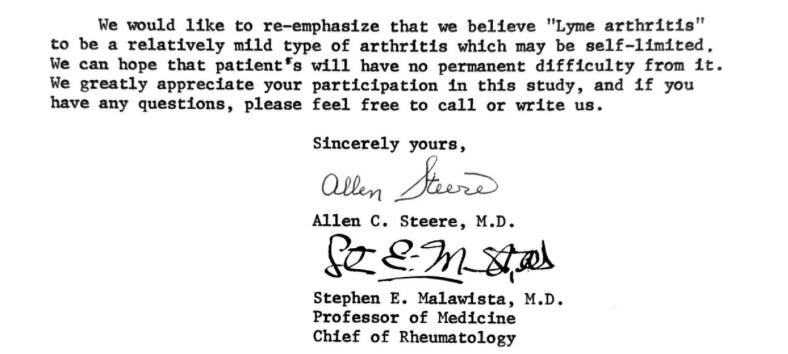

Yet none of these potentially life-threatening symptoms were mentioned in Steere’s “I solved the Lyme mystery” announcements, first at a 1976 conference [4], then in the 1977 article “Lyme arthritis: an epidemic of oligoarticular arthritis in children and adults in three Connecticut communities.” [5] (To be fair, subsequent publications documented some of the neurological symptoms.)

The wrong path

In a move that would send researchers down a dead end for years to come, Steere declared that Lyme disease was primarily a problem of swollen joints, not a disease that affected the nervous system, the brain, the heart, and other organs.

Other medical experts criticized his premature labeling of this disease as a “relatively minor type of arthritis,” including:

—Franz J. lngelfinger, MD, the editor of The New England Journal of Medicine, who rejected Steere’s discovery article, wrote, “Although reviewers and editors were impressed by the interest your studies have generated, you were unable to identify an etiologic agent and apparently actually saw yourself only 20 symptomatic patients.” [6]

—William E. Mast, MC and William, M. Burrows, MC, the Groton military physicians who published the first Connecticut Lyme case studies, wrote in a JAMA rebuttal letter: “On exchange of patients and information with Dr. Steere and the group at Yale investigating “Lyme arthritis,” it is the consensus that we are all dealing with the same process. It is apparent that the term “Lyme arthritis” is much too restrictive since there have been cases from the Connecticut and Rhode Island shores and the incidence is expected to be more widespread.” [7]

—Raymond Dattwyler, MD, Professor of Pathology, Microbiology and Immunology, Medicine, and Pediatrics at New York Medical College said, “It’s unfortunate that in the U.S., the rheumatologists studied Lyme disease first. Lyme disease is a multisystemic infectious disease that impacts many organs. But because the early work was done by rheumatologists, the prism through which we view the disease was artificially narrow, and impeded research for years.” [8]

Words from the grave

Polly wasn’t a trained epidemiologist, but she approached the problem like a true scientist—she wrote everything down so nothing would be missed. And as the people around her got sicker, she doubled down on her resolve to get help for these very sick people:

I firmly believe in the politics of numbers. One person, or even six in a family such as ours, does not have the power that was acquired by the ever-increasing number of people eventually involved. Proper diagnosis was further hampered by the fact that the patients from our area did not go to just one medical center, where, if we had, the high incidence of these strange symptoms might possibly have been picked up earlier. Instead, because of our geographic location, we, in fact, went to specialists in New Haven, Middletown, Hartford, and even New York and Boston. Perhaps it was the adversity that I encountered in the early pursuit for knowledge concerning our constant maladies that made me persist more than I would have otherwise.

Despite her efforts, it’s still difficult for patients to get diagnosed and treated, especially in the later stages of the disease. According to MyLymeData’s registry of 12,000-plus Lyme patients, about half had to see 5 or more clinicians over 3 or more years before receiving an accurate diagnosis. [9]

Little progress in 43 years

Forty-three years after its discovery, we still don’t have a reliable Lyme screening test, and about a quarter of patients treated with the standard dose of antibiotics go on to suffer from ongoing symptoms. [10] The CDC estimates that there are almost 500,000 new cases a year and growing. [11] And an analysis of NIH Lyme-related research grants from 2013-2021 revealed that less than 1% was spent on looking for better treatment protocols. [12]

Regrettably, Polly’s perspective on what went wrong in the 1970s still holds true today. The medical system still hasn’t figure out how to deal with complex chronic diseases like long COVID, Lyme disease, or ME/CFS (chronic fatigue).

It is only in looking back on the discovery of this disease that I see that it fit into the classic pattern of denial and resistance to the unknown until it reached a point where it could no longer be ignored. Most doctors are overloaded in just trying to alleviate known problems, thereby making it difficult for anyone with a new set of symptoms to compete for the clinician’s time. It is easier to decide that the patient is hypochondriacal than to deal with the unknown. Furthermore, in this age of specialization, the total picture of the patient’s health is often lost when the patient goes from specialist to specialist to be treated for individual symptoms.

This history shows that the definition of Lyme disease went off track early on and then diverged further from reality under the influence of vaccine developers and medical insurers who found it more profitable to deny the chronic, relapsing manifestations of the disease. The legacy of Lyme disease, which continues to spread unabated, will continue to haunt us unless we address this problem in a more honest and effective way.

Kris Newby is an award-winning medical science writer and the senior producer of the Lyme disease documentary UNDER OUR SKIN. Her book BITTEN: The Secret History of Lyme Disease and Biological Weapons won three international book awards for journalism and narrative nonfiction. Previously, Newby worked for Stanford Medical School, Apple, and other Silicon Valley companies.

This article is republished by permission from The BITTEN FILES on Substack, July 12, 2024. Learn more here.

References

1. Petersen LR, et al. “Epidemiological and clinical features of 1,149 persons with Lyme disease identified by laboratory-based surveillance in Connecticut.” Yale J Biol Med. 1989 May-Jun;62(3):253-62.

2. Polly Luckett Murray Papers, Medical Historical Library, Harvey Cushing/John Hay Whitney Medical Library, Yale University.

3. Photo courtesy of Polly’s son, David Murray.

4. https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/24791517-1976-steere-lyme-definition-presentation

5. Steere AC, et al. Lyme arthritis: an epidemic of oligoarticular arthritis in children and adults in three Connecticut communities. Arthritis Rheum. 1977 Jan-Feb;20(1):7-17.

6. Stephen E. Malawista Papers, Archives at Yale. https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/24797919-1976-jama-rejects-steere-article

7. Mast WE, Burrows WM. Erythema Chronicum Migrans and “Lyme Arthritis.” JAMA. 1976;236(21):2392. doi:10.1001/jama.1976.03270220014011 https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/349662

8. Weintraub, Pamela, Cure Unknown, New York : St. Martin’s Press, 2008. (A must read if you want to understand Lyme disease history.)

9. 2019 MyLymeData Chart Book. https://www.lymedisease.org/mylymedata-lyme-disease-research-report/

10. “Why Lyme disease treatment sometimes doesn’t work.” LymeDisease.org https://www.lymedisease.org/lyme-treatment-sometimes-fails

11. CDC Lyme Disease Surveillance and Data. https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/data-research/facts-stats

12. Kris Newby analysis of NIH RePORTER data: https://report.nih.gov/funding/categorical-spending#/

We invite you to comment on our Facebook page.

Visit LymeDisease.org Facebook Page