MEDICAL DETECTIVE #4: How to survive in a tick-filled world

This article was originally posted on Dr. Richard Horowitz’s Medical Detective Substack. You can find more helpful content by subscribing here.

If I were to conjure up a global menace in a teeny-tiny package, I wouldn’t have to look far for inspiration. It’s already there, crawling down the legs of a deer or a dog and up the stalk of grasses or shrubs or plants in your garden, all primed and ready to latch on to your tender skin and take a nice big chomp!

It’s a tick-filled world and we’re stuck living in it.

And you know what’s making it worse? Climate change. The warmer the weather, the easier it is for ticks to breed. Increases in global temperatures increase the reproductive rates of insects, so we are seeing an explosion of not only pathogen-filled ticks, but also mosquitos that are potentially transmitting West Nile, Zika virus, Chikungunya, Dengue, other viruses and even malaria in the US.

The same pest-pocalypse is happening to other biting insects like fleas, mites, lice, etc. that can transmit a broad range of organisms, including Bartonella (more about this in future articles).

So remember, these insects, including ticks, may contain multiple bacteria, viruses, and parasites, and getting one bite can lead to more than one disease.

In fact, in my 40+ year experience treating chronically ill individuals, co-infections with multiple bacteria, viruses, and parasites are the rule, not the exception. And people usually end up getting multiple bites from ticks over their lifetime because these unbelievably annoying creatures are spreading rapidly and present in every corner of the globe (even Antarctica!).

Gruesome–but necessary–reading

Learning about how ticks live and feed makes for pretty gruesome reading.

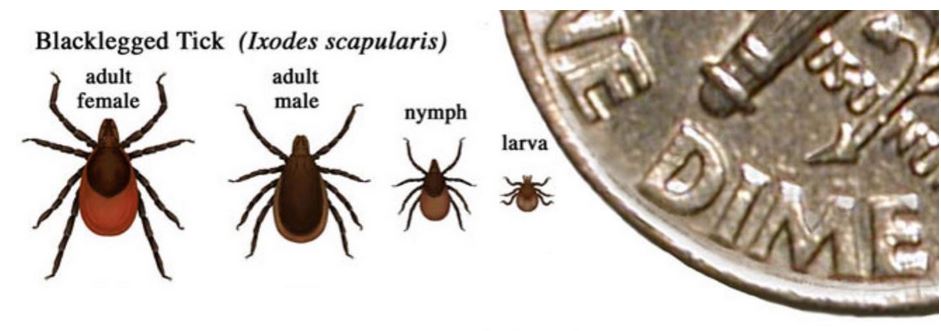

Suffice to say that they go through four life stages: egg, six-legged larva, eight-legged nymph, and adult. The only course they have on their menu is blood, thanks to their bites on either animals or humans.

If they bite an animal that’s already carrying a pathogen, they can then transmit that bug to the next unlucky recipient of their cunning. Hopefully that won’t be you!

.

And get this–some of these ticks are hermaphrodites, like the rapidly spreading Asian bush tick, Hemophylis Longicornis, which means they can reproduce without mating. This also means that they are reproducing more rapidly than other ticks.

Although they haven’t been proven yet to transmit some of the multiple infections now being found in them (Borrelia burgdorferi, i.e., Lyme disease, tularemia, Rickettsia like Rocky Mountain Spotted fever, Heartland, and Bourbon viruses), time will tell.

In Asia, these same ticks can cause alpha gal syndrome, the “red meat allergy” as well as SFTS (Severe Fever and Thrombocytopenia Syndrome), a potentially fatal illness.

Bottom line: if you get bitten, you want to know what kind of tick it is, and what pathogens it contains.

Different varieties in different regions

As you’ve unfortunately realized by now, there are many varieties of ticks that live in different areas of the U.S. (I’ll discuss this in an upcoming posting, but for now you can check this map: https://www.cdc.gov/ticks/data-research/facts-stats/geographic-distribution-of-tickborne-disease-cases.html.)

Not every tick is a carrier of a pathogen–only the black-legged deer tick can transmit Lyme Disease, for example–so getting bitten doesn’t automatically guarantee that you’ll get sick. But enough ticks are infected in this country and abroad, and can spread any or more of these 20 diseases with just one bite, as you can see from this CDC list:

- Anaplasmosis

- Babesiosis

- Borrelia mayonii

- Bourbon virus

- Colorado tick fever

- Ehrlichiosis

- Hard tick relapsing fever (Borrelia miyamotoi)

- Heartland virus

- Lyme disease

- Powassan virus

- Q-fever (Coxiella burnetti)

- Rickettsia parkeri rickettsiosis

- Rocky Mountain spotted fever

- Soft tick relapsing fever (multiple species, i.e., B. hermsii, B. parkerii, B. turicatae)

- STARI

- Tularemia

- Typhus

- 364D rickettsiosis

Where Are Ticks Lurking?

Ticks are tenacious, and can be found even in urban environments you’d think would be free of them. According to the New York City Department of Health, for example, there were 3,323 (2,482 new ones and 741 positive ones from previous years) reported cases of Lyme disease in NYC residents in 2023. This is up from 2,524 cases in 2022.

There were also 77 reports of anaplasmosis and 116 of babesiosis in 2023. I suspect that these cases were picked up while in any of the city’s many parks, but who knows?

These numbers are likely gross underestimates of how bad the problem truly is, because several of the diseases we will be discussing can’t easily be picked up on standard blood tests, and doctors may not know to always look for them since some of the symptoms are non-specific and overlap other illnesses.

As I’ve said in earlier posts, last year alone, the CDC reported 476,000 cases of Lyme disease in the US, and their recent implementation of a revised case definition reported that case counts are rising where the incidence was 1.7 times the annual U.S. average in 2017–2019, an overall 68.5% increase, rising with patient age.

If you’re going outside to an environment where ticks are hiding—going to a park, hiking on trails in fields or forests, or while gardening, for example—follow these tips.

Tick Lookout Tips

- Ticks can’t ‘officially’ fly, although static electricity from animals results in ticks being pulled by these electric fields across air gaps measuring several of their body lengths, resulting in leaps that one could almost define as flying. They also don’t jump, so they have to crawl from host to host as their primary means of attachment. They lurk. They wait. (This is called “questing.”)

- The little monsters are clever enough to detect a potential host by sensing body heat, moisture, odors, or carbon dioxide; or by the vibrations of someone passing by. Although the deer tick (Ixodes scapularis in the northeastern US) or Ixodes pacificus (in the Pacific US), can sense your presence from 12 feet away and come running, some of these ticks like the lone star tick (Ambylomma Americanum) can sense your heat and carbon dioxide from up to 50 feet away. They will come after you to bite you from quite a distance, even if you are not in high grass or directly exposed.

- As soon as they can climb onto where they aren’t wanted, they either latch on in one spot, or take their time wandering around your body where skin might be thinner and easier to bite.

- So when you go outside, stay in the middle of any trails, away from tall grasses, branches, and leaves. Try not to brush up against any foliage. Ticks also like to quest in border areas in the yard or park and near bird feeders.

- If you have a yard, keep the grass short. If you have a compost pile, or piles of leaves, stay out of them!

- Don’t sit directly on the ground, on large stones or fallen logs, or on stone or brick walls.

This is part one of a two-part series about ticks originally published on Substack by Dr. Richard Horowitz. You can read the second part in the next Substack.

See also:

“Medical Detective” series brings information you need to know

MEDICAL DETECTIVE #1: An overview of Lyme disease signs and symptoms

MEDICAL DETECTIVE #2: How Will I Know If I Have Lyme Disease?

MEDICAL DETECTIVE #3: Let’s Talk About Lyme Rashes

Dr. Richard Horowitz has treated 13,000 Lyme and tick-borne disease patients over the last 40 years and is the best-selling author of How Can I Get Better? and Why Can’t I Get Better? You can subscribe to read more of his work on Substack or join his Lyme-based newsletter for regular insights, tips, and advice.

We invite you to comment on our Facebook page.

Visit LymeDisease.org Facebook Page