Prof. Holly Ahern’s Lyme disease comments to Australian Senate

The Australian Senate has launched an inquiry into the access to diagnosis and treatment for people in Australia with tick-borne diseases. Professor Holly Ahern of the United States recently submitted the following written comments and was also asked to give verbal remarks. (See video at end of this article.)

Dear Committee Members:

I am a scientist, professor of microbiology, and co-founder of a Lyme disease advocacy organization in New York State. I am also the Scientific Advisor for the Focus on Lyme Foundation in Arizona, which has funded research on several projects directed at improving the state of diagnostic testing for Lyme disease and other tick-borne illnesses.

I have served on several state and federal committees convened to address the growing problem of tick-borne diseases in the United States, most recently the 2022 Dept. of Health and Human Services, Tick Borne Disease Working Group (TBDWG).

But most of all, I am mother of a daughter who went from a record setting collegiate All American swimmer to bed bound and disabled over the course of only a few weeks. She lost years of her life as a result of flawed medical guidelines that prioritize care for patients early in the infection, while providing only minimal guidance for the diagnosis and care of patients in later stages of the disease.

In my daughter’s case, we saw the tick bite but she developed no rash. Fever, profound fatigue, widespread pain, and other symptoms began months later, and were attributed to a viral illness. The difficulties we faced in getting her illness diagnosed and appropriately treated in 2010 match those of hundreds of thousands of other people with Lyme disease in the United States and Europe, and also in Australia.

Biologically complex organism

Lyme disease is a bacterial infection caused by a microbe with global distribution. They are transmitted to humans by several species of tick. The bacteria are biologically complex. They adapt and survive in environments that would kill most other bacteria.

During human infection, some subgroups (genospecies) of these bacteria linger in the bloodstream, while others disseminate to connective tissue-rich areas of the body. Regardless, infection triggers profound immune system and other physiological events, leading to a wide range of symptoms that vary significantly among patients and can be quite severe.

The standard medical definition implies that the overwhelming majority of Lyme borreliosis (Lyme disease) patients are infected with the same bacteria and have the same uniform disease presentation, which is straightforward to diagnose and treat. As defined, Lyme disease is caused by only a few specific genospecies of Borrelia (now named Borreliella). Several other genospecies of Borrelia are associated with diseases collectively referred to as “Relapsing Fever borreliosis.”

Differences between the two diseases are subtle. Relapsing Fever Borrelia fail to produce the skin manifestation (erythema migrans or “bull’s-eye” rash) that is noted in Lyme disease; however, other symptoms are very similar. Existing diagnostic tests for Lyme disease don’t detect infections caused by Relapsing Fever Borrelia.

Thus, a patient may be bitten by a tick and infected with a Relapsing Fever Borrelia, such as B. miyamatoi, show all the symptoms that a patient with Lyme disease would have, but may not be diagnosed or treated for the infection because the EM rash did not appear and/or the standard lab tests for Lyme disease were negative.

Australia-specific concerns

Given the diversity of Borrelia genospecies and the symptom overlap, research initiatives could be broadened to consider if the cases of Lyme-associated chronic illness noted to occur in Australia might be due to infection with other, potentially novel genospecies of Borrelia and to investigate the range of animal species that could serve as reservoir hosts, and the range of tick species that might serve as disease vectors.

In Australia, only a limited number of small-scale studies have attempted to date to investigate the etiological, epidemiologic, or microbiological factors associated with reported cases of Lyme disease. They do not provide sufficient data to conclude that Lyme disease or Relapsing Fever is not a medical concern or that these diseases should not be considered a significant public health issue.

There are indicators that bacteria capable of causing borreliosis are present in Australia. One study has identified a unique genospecies of Borrelia in Australian ticks. This genospecies, recently named Borrelia tachyglossi, shares gene sequence homologies with Borrelia in both the Lyme and Relapsing Fever groups.

The significance of this discovery should not be underestimated, and should inspire additional research.

Some public health officials contend that Lyme disease is not acquired in Australia and only occurs as a result of travel abroad. Regardless, reliance on medical guidelines that have failed Lyme disease patients in the United States and European Union will result in the same problems of underdiagnosis, lack of timely and appropriate treatment, and increased risk of Infection-Associated Chronic Illness (IACI) – a health threat that gained acceptance in patients who suffered with Long Covid.

Infection-associated chronic illness

This syndrome was recognized in a National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine meeting convened in 2023 to better define and advance research and treatment of post-infection chronic illnesses associated with bacterial or viral infections, including Lyme disease.

A barrier that limits access to care for patients with what might be called Long Lyme is enshrined in medical guidelines that direct the diagnosis and care of Lyme disease and borreliosis patients worldwide. The guidelines, written by U.S. based physician-researchers, assert that antibiotic treatment of Lyme disease resolves the illness. Any aftermath, the guidelines contend, is usually due to other conditions or can’t be medically explained.

This contention falls short for people who are diagnosed months to years after the infection begins and are inadequately treated. Lyme disease is difficult to diagnosis, particularly early in the infection, because the only recognized clinical sign of Lyme disease – the EM skin rash – is not a reliable disease marker, and existing blood tests for Lyme disease are highly inaccurate, especially during the first few weeks of infection.

Early treatment essential

Of crucial importance, if Lyme disease is diagnosed early within a week or two of infection and appropriately treated with an antibiotic, the majority of patients recover.

However, research shows that even after prompt diagnosis and appropriate treatment, 15 – 20% of patients will develop a Lyme-associated chronic illness with debilitating symptoms: profound fatigue, joint and/or muscle pain, sound and light sensitivity, and moderate to severe levels of “brain fog,” that persist for more than six months and greatly impair quality of life.

The percentage of cases that progress to chronic illness is even higher in those who are diagnosed months or sometimes years after the initial infection occurred. Estimates range from 20 – 30% to even higher when data from patient registries such as MyLymeData is reviewed.

At present, there are no broadly accepted treatment protocols for patients with Lyme-associated chronic illness. Thus, early diagnosis and prompt and appropriate antibiotic treatment of Lyme disease should be considered an important aspect of patient care.

However, diagnosis of Lyme disease during the early stages of the infection remains challenging, even in the U.S. where it is presumed that health care providers have more experience with the disease.

Although some healthcare providers in the U.S. and elsewhere are aware of the diagnostic challenges with Lyme disease, in particular the variability of the appearance of EM rash and the limitations of the existing diagnostic tests, many are not.

Diagnostic criteria is problematic

And this appears to be true in Australia, based on the information and recommendations made in the NSW Lyme Disease Fact Sheet. If the diagnostic criteria do not fit the disease, then the disease won’t be diagnosed.

I was appointed to the Testing and Diagnostics Subcommittee of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Tick Borne Disease Working Group (TBDWG), which delivered its Report to Congress in 2018.

This subcommittee considered and identified key issues related to the existing medical guidelines that dictate both the diagnosis and treatment of Lyme disease. We reviewed the available science and spoke with experts on Lyme diagnosis. We concluded that the diagnostic criteria, which had remained largely the same for over 30 years, failed in several ways.

For one, the distinct skin rash that resembles a “bull’s-eye” is not reliable as a disease marker for Lyme disease. Medical guidelines suggest the rash appears in the classic bulls-eye form in 70% of Lyme disease cases, other studies show this rate to be much lower. Even in confirmed Lyme disease cases, there is significant variability in how the rash actually looks in terms of its size, shape, color, and pattern. The appearance of the rash also varies according the sex and skin color of the patient.

Failure to recognize

Even healthcare providers in areas where Lyme disease more commonly occurs have difficulty recognizing a skin rash as an erythema migrans, and I would like to provide a direct example that shows this to be true.

The pictures below are shown with permission of the parents. The mothers of the children saw the rash and were concerned that the rashes were associated with Lyme disease. Both saw health care providers – one went to an Urgent Care center, the other to a pediatrician – in upstate New York, which is considered a region “highly endemic” for Lyme disease.

Yet in both cases, the parents were told that the rash was probably due to dermatitis or an insect or spider bite, NOT Lyme disease. Why? Because no attached tick had been observed on the child at or near the site of the rash.

While both rashes look like an EM rash and occurred in an area of the US where Lyme disease is common, neither child was initially diagnosed with Lyme disease or prescribed an antibiotic.

How would YOU as a parent feel if this was your child?

Two-tier serology

Another factor complicating Lyme disease diagnosis is the recommended laboratory test for Lyme disease, which is two-tier serology.

“Two-tier” involves two separate tests – the first being a sensitive but not very specific immunoassay that detects a general antibody response to the infection. Diagnostic standards developed for Lyme disease in 1994 – 30 years ago – hold that this test must return an equivocal or positive result before a second, more specific test is performed which must also be positive to support a diagnosis of Lyme disease.

The usefulness of this approach as a diagnostic tool for Lyme disease has been under debate pretty much from the beginning of the disease’s history in the U.S. in the 1980s.

As discussed in the Testing and Diagnostics Subcommittee Report and full Report to Congress – two-tier serology was noted for poor clinical accuracy. In other words, it misses many cases.

Most sources agree that the sensitivity of the two-tier test is very low – less than 30% accurate – during the early stages of the infection. Sensitivity refers to the ability of a diagnostic test to designate a person with a disease as positive – in the case of Lyme disease, a sensitivity of 30% means that only 3 out of 10 people who actually have Lyme disease will have a positive test result.

For late-stage Lyme arthritis, the form of Lyme disease discovered in the U.S. in the early 1980s that the test was developed to detect, two-tier serology is fairly accurate. But for other presentations (neurological), the sensitivity is much lower

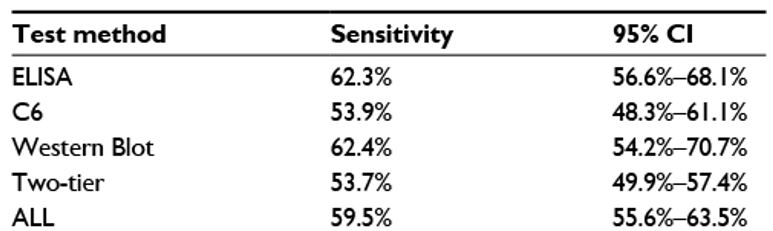

A 2016 biostatistical review of over 50 studies on the characteristics of available test kits for Lyme disease found that across all disease stages and presentations, the tests were accurate in 59.5% of cases. A summary of the sensitivity of the various test kits is shown in the table below:

Source: “Commercial test kits for detection of Lyme borreliosis: a meta-analysis of test accuracy.” (Cook MJ and Puri BK. Int J Gen Med. 2016;9:427-440).

Because the two major criteria for diagnosing a case of Lyme disease – the EM rash and the two-tier test – are not good disease indicators, it is likely that most cases of Lyme disease are not diagnosed during the early, most treatable stage of the disease. And this would also be true for Australian Lyme disease patients, since the guidance there is very much the same.

Barriers to care for Lyme disease patients

In 2022, I served on the HHS TBDWG Access to Care Subcommittee which submitted a Report to Congress in 2022. Our work focused on the barriers to care that exist for Lyme disease patients.

The rigid and unchanging medical guidelines that dictate the standard of care is one such barrier to care. A study funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health on cases of pediatric Lyme disease was published in 2023. One of the authors is the NIH program officer for Lyme disease, who is also an infectious disease doctor. The abstract asserts that the data shows a majority of children diagnosed with Lyme disease recovered after standard antibiotic treatment, and only a “notably small percentage” of the children continued to have symptoms after treatment.

The press release that accompanied the paper asserted that “this study supports previous data showing an excellent overall prognosis for children with Lyme disease, which should help alleviate understandable parental stress associated with lingering non-specific symptoms among infected children.”

So how would YOU define a “notably small percentage” of children who continue to have symptoms after diagnosis and antibiotic treatment for Lyme disease. Less than 1% maybe?

A review of the actual data indicates that the researchers, and the governmental agency in charge of Lyme disease research in the United States, considers a “notably small percentage” to be 22% (nearly 1 out of 4). These were children who did not return to good health for months after receiving the standard treatment for early Lyme disease. Approximately 1 in 10 (9%) of the children in the study demonstrated varying degrees of “functional impairment” that continued for more than 6 months. This “functional impairment” could possibly become a disability that might last for the rest of their lives.

Biased and misleading

The paper’s abstract summarizing the research findings, and the press release announcing them were biased and misleading. They were written to defend the standard of care, with little regard for the children (or their parents) who might have to live for the rest of their lives with a debilitating chronic illness.

Biases in medical research perpetuates the medical status quo that Lyme disease and other forms of borreliosis are “hard to catch and easy to cure.” An abundance of scientific, epidemiological, medical, and patient-driven research shows that Lyme disease is, in fact, not that hard to catch and may be difficult to cure.

As Michael J. Fox, a Parkinson’s disease patient and 2024 Presidential Medal of Freedom recipient, put it: “This message is so simple, yet it gets forgotten. The people living with the condition are the experts.”

Thank you extending the invitation to make a submission to your committee. If you have questions or would like me to send you additional information or references related to the information provided, please let me know.

Best regards,

Holly Ahern, MS, MT(ASCP) ahernh@sunyacc.edu

Associate Professor of Microbiology, SUNY Adirondack

Co-founder and Chief Scientific Officer, Aces Diagnostics Inc. Woman-led start up company founded to advance research, development, and commercialization of a clinically accurate diagnostic test for Lyme disease.

Co-founder and Vice President, Lyme Action Network (501-c-3 advocacy organization in NY USA)

Scientific Advisor, Focus on Lyme (501-c-3 advocacy organization in AZ USA)

Phase 1 and 2 Judge, LymeX Diagnostic Prize Competition (HHS/Steven and Alexandria Cohen Foundation public private partnership to advance Lyme disease diagnostics) 2022-2024

NYS Tick Borne Disease Working Group, 2018, 2021 – 2023

HHS Tick Borne Disease Working Group, Access to Care Subcommittee, 2022

HHS Tick Borne Disease Working Group, Diagnostic and Testing Subcommittee 2018

NYS Senate Lyme and Tickborne Disease Advisory Group (2015 – 2020)

(Video is cued to the beginning of Holly Ahern’s portion, at approximately 3:46.)

We invite you to comment on our Facebook page.

Visit LymeDisease.org Facebook Page