TOUCHED BY LYME: Shapiro and Walker tried having it both ways. It didn’t work.

The Tick-Borne Disease Working Group is supposed to bring together 14 people—scientists, doctors, health officials, patient advocates—with different areas of expertise and divergent views about Lyme and other tick-borne conditions.

In concept, members would share their own perspectives and knowledge, while paying respectful attention to what others had to offer.

Ideally, their final product—the 2020 Report to Congress—would be an amalgam of what they all brought to the table. And it would be more powerful precisely because so many differing voices contributed to it and achieved consensus.

Alas, that ideal falls far short of reality these days. Exhibit A: the Working Group’s October 27 online meeting.

There was lots of strange stuff happening and it was at times hard for those of us in the remote audience to understand it. (Note to Working Group: Can you please put future meetings on Zoom or another video platform? Since we couldn’t see who was talking, sometimes the conversation was impenetrable.)

As the panel slogged through the wording of various chapters of its upcoming report, deciding what to keep and what to toss, several curious issues emerged.

First, what’s a minority response and who gets to file one?

When a group like this generates an official document, it’s assumed that its members agree with the report’s content. That’s the process of achieving consensus. Over months of discussion, you give a little, you get a little—until the final report is something all panelists can live with. At various points, group members vote on what should be included in their final report.

However, if a member strongly disagrees with one or more parts of the finished product, that person can submit an explanation of why. This “minority response” is included along with the main report. (Kind of like a Supreme Court justice writing a dissenting opinion.)

Typically, in order to file a “minority response,” however, the person writing it has to BE in the minority—at least on that issue. They should also have tried in good faith to reach a consensus on the issues by explaining their perspective to the group and trying to obtain buy in or achieve a compromise on the matter after robust discussion. Failing that, they can then vote “no” on something that most panelists have voted “yes” on–and then submit their minority opinion.

Working towards consensus

As patient representative Pat Smith noted in Tuesday’s discussion, “A consensus process means you go in with the idea you are going to work towards a common goal and hopefully get to where everybody agrees.”

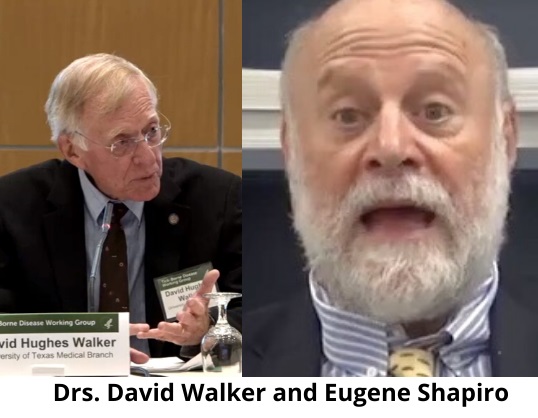

But that hasn’t happened with IDSA representative Dr. Eugene Shapiro, who has never had working towards a common goal with the Lyme community on his “to do” list. Shapiro has a history of publicly denigrating Lyme patients and working against their interests (See: Why we think Shapiro should be removed from the TBD Working Group.)

Furthermore, throughout his tenure on this panel, Shapiro has often skipped meetings entirely, making a point of passing his proxy vote to Co-chair David Walker—who, as a moderator, is supposed to be neutral and not take sides.

Thus, there were many group discussions that Shapiro had no part in whatsoever, and yet he was allowed to go on record as voting a certain way because the Co-chair voted for him. (See: Proxy votes violate spirit of TBD Working Group.)

At the Working Group’s September 22 meeting, Shapiro got into a dust-up with Pat Smith regarding the wording of a passage. He then apparently threw up his hands and said something along the lines of, “Well, don’t worry about it. I’ll just put that in my minority report.”

To which Pat replied (I’m paraphrasing): “Be my guest. But remember, you have to vote no on something before you can submit a minority response. Otherwise, you’re not in the minority.”

A slew of individual responses?

Behind the scenes wrangling led Pat to seek clarification at the Oct. 27 meeting. She argued that letting everybody submit their own personal reports willy-nilly is a dumb idea. (My phrasing, not hers.)

Taken to the extreme, 14 members of the Working Group could all submit a slew of individual responses—making for a pretty unwieldy Report to Congress, don’t you think?

Pat made two motions regarding this matter, including one that spelled out that a panelist did indeed have to vote against the majority in some aspect of a chapter, in order to submit a minority response.

She was apparently pretty persuasive, since the motions passed. Even Co-chair Walker voted “yes” on both of them, for himself and Shapiro, who had stepped off the call for the duration of that discussion.

Then, the group broke for lunch. When they returned, Shapiro was back on the line. When he figured out that the group had voted to allow minority opinions only when a “no” vote had occurred, Shapiro sounded irritated. (Ticked off, might we say?)

When he complained about the change, somebody said, “Gene, you voted yes.”

That’s another reason I wish this had been on video. I would have liked to have seen the expression on his face.

This Working Group panel has two more meetings: November 17 and December 2—where this drama may continue to unfold. Stay tuned for details about submitting comments and watching the proceedings online.

See also:

Tweet summary of Oct. 27 TBDWG meeting

My comments to TBDWG about Lyme patient representation

Phyllis Mervine to TBDWG: ditch the misleading CDC Lyme map

TOUCHED BY LYME is written by Dorothy Kupcha Leland, LymeDisease.org’s Vice-president and Director of Communications. She is co-author of When Your Child Has Lyme Disease: A Parent’s Survival Guide. Contact her at dleland@lymedisease.org.

We invite you to comment on our Facebook page.

Visit LymeDisease.org Facebook Page