NEWS: Using genetic engineering to combat malaria, Lyme and other illnesses

Researchers at the University of Maryland show that a genetically engineered fungus may help fight several vector-borne diseases. But the press release contains no discussion of potential risks of releasing such genetically engineers materials into nature. What unintended consequences might result?

A press release from the University of Maryland (February, 2011)

Study Shows UMD Designed Fungi Can Combat Malaria, Lyme Disease & Other Bug-Borne Illnesses

COLLEGE PARK, Md. – New findings by a University of Maryland-led team of scientists indicate that a genetically engineered fungus carrying genes for a human anti-malarial antibody or a scorpion anti-malarial toxin could be a highly effective, specific and environmentally friendly tool for combating malaria, at a time when the effectiveness of current pesticides against malaria mosquitoes is declining.

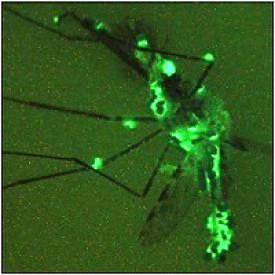

Pictured is an Anopheles mosquito infected with a strain of the Metarhizium anisopliae fungus that has been labeled with a gene for fluorescence. Image by Weiguo Fang, University of Maryland. |

In a study published in the February 25 issue of the journal Science, the researchers also say that this general approach could be used for controlling other devastating insect and tick bug-borne diseases, such as or dengue fever and Lyme disease. “Though applied here to combat malaria, our transgenic fungal approach is a very flexible one that allows design and delivery of gene products targeted to almost any disease-carrying arthropod,” said Raymond St. Leger, a professor of Entomology at the University of Maryland.

“In this current study we show that spraying malaria-transmitting mosquitoes with a fungus genetically altered to produce molecules that target malaria-causing sporozoites could reduce disease transmission to humans by at least five-fold compared to using an un-engineered fungus,” St. Leger said.

St. Leger, his post doctoral researcher Weiguo Fang and colleagues at the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health and the University of Westminster, London created their transgenic anti-malarial fungus, by starting with Metarhizium anisopliae, a fungus that naturally attacks mosquitoes, and then inserting into it genes for a human antibody or a scorpion toxin. Both the antibody and the toxin specifically target the malaria-causing

parasite P. falciparum. The team then compared three groups of mosquitoes all heavily infected with the malaria parasite. In the first group were mosquitoes sprayed with the transgenic fungus, in the second were those sprayed with an unaltered or natural strain of the fungus, and in the third group were mosquitoes not sprayed with any fungus.

The research team found that compared to the other treatments, spraying mosquitoes with the transgenic fungus significantly reduced parasite development. The malaria-causing parasite P. falciparum was found in the salivary glands of just 25 percent of the mosquitoes sprayed with the transgenic fungi, compared to 87 percent of those sprayed with the wild-type strain of the fungus and to 94 percent of those that were not sprayed. Even in the 25 percent of mosquitoes that still had parasites after being sprayed with the transgenic fungi, parasite numbers were reduced by over 95 percent compared to the mosquitoes sprayed with the wild-type fungus.

“Now that we’ve demonstrated the effectiveness of this approach and cleared several U.S. regulatory hurdles for transgenic Metarhizium products, our principal aim is to get this technology into field-testing in Africa as soon as possible,” St. Leger said. “However, we also want to test some additional combinations to make sure we have the optimized malaria-blocking pathogen.”

|

Noting that the University of Maryland has pioneered the science and practice of creating transgenic fungi, St Leger said that he and colleagues at Maryland and at partnering institutions are already working to create genetically engineered fungi that can be used to reduce transmission of other illnesses, like Lyme disease and sleeping sickness. In related work, they are employing genes encoding highly specific toxins to produce hypervirulent pathogens that can control pests like locusts, bed bugs and stink bugs.

“Insects are a critical part of the natural diversity and the health of our environment, but our interactions with them aren’t always to our benefit,” said St. Leger, who is widely recognized for research that employs insects and their pathogens as models for understanding how pathogens in general cause disease, adapt and evolve, and in the application of that understanding to the creation of new methods for safely reducing crop destruction, disease transmission and other damaging insect impacts.

The Malaria Challenge

Infection by malaria-causing parasites results in approximately 240 million cases around the globe annually, and causes more than 850,000 deaths each year, mostly children, according to the World Health Organization. Most of these cases occur in sub-Saharan Africa, but the disease is present in 108 countries in regions around the world. Treating bed nets and indoor walls with insecticides is the main prevention strategy in developing countries, but mosquitoes are slowly becoming resistant to these insecticides, rendering them ineffective.

“Malaria prevention strategies can greatly reduce the worldwide burden of this disease, but, as mosquitoes continue to acquire resistance to currently used methods, new and innovative ways to prevent malaria will be needed, experts say.

Pictured is a bed bug infected with a fungus labeled with a gene for fluorescence. Image by Weiguo Fang and Kevin Ulrich, University of Maryland. |

One such strategy is killing Anopheles mosquitoes by spraying them with the pathogenic fungus M. anisopliae. Previous studies by African, Dutch and British scientists have found that this method nearly eliminates disease transmission but only when mosquitoes are sprayed soon after being infected by the malaria parasite. The difficulties with this strategy are that it requires high coverage with fungal biopesticides to ensure early infection, and is not sustainable in the long term. If spraying mosquitoes with M. anisopliae kills them before they have a chance to reproduce and pass on their susceptibility, mosquitoes that are resistant to the fungus will soon become predominant and the spray will no longer be effective.

The approach developed by St. Leger and his colleagues avoids these problems because their engineered strains selectively target the parasite within the mosquito, and allow the fungus to combat malaria when applied to mosquitoes that already have advanced malaria infections. In addition “Our engineered strains slow speed of kill enable mosquitoes to achieve part of their reproductive output, and so reduces selection pressure for resistance to the biopesticide,” St. Leger said. “Mosquitoes have an incredible ability to evolve and adapt so there may be no permanent fix. However, our current transgenic combination could translate into additional decades of effective use of fungi as an anti-malarial biopesticide.”

The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), part of the National Institutes of Health, funded this research.

|

We invite you to comment on our Facebook page.

Visit LymeDisease.org Facebook Page