There is growing evidence that certain types of tick bites can trigger alpha-gal syndrome (AGS) a life-threatening allergy to red meat and meat-related products.

In some individuals, it appears tick bites can result in the sensitization to a carbohydrate known as galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose, or “alpha-gal” for short. This sugar molecule is found in most mammals you might be likely to eat, but not in fish or fowl.

Most recognized food allergies, such as to peanuts or shellfish, will prompt an immediate reaction after being consumed. That’s not the case with AGS, however, which can take up to eight hours (or even more) after exposure to produce a reaction.

Note: exposure to alpha-gal via inhalation, injected drugs or vaccines can cause an immediate reaction.

Examples of commonly consumed mammalian meats that contain alpha-gal include beef, pork, lamb, goat, venison and buffalo. Common foods that are derived from mammals include lard, milk, cream, ice cream, and cheese—although the majority of AGS patients do tolerate dairy products.

Personal products that use ingredients containing “hydrolyzed protein” (gelatin), lanolin, glycerin, collagen, or tallow are particularly problematic.

Additional products that can bring on an alpha-gal reaction are jello, gelatin capsules, certain medications, pig or cow heart valves, surgical mesh, certain vaccines and unlabeled “natural flavorings” in foods.

Some people with AGS also react to carrageenan, a common food additive made from red algae, which also contains alpha-gal. (So even being strictly vegan won’t necessarily protect you from AGS reactions.)

How are ticks involved in alpha-gal syndrome?

Alpha-gal meat allergy has been reported all over the world including Asia, Australia, Central America, Europe, Germany, Japan, South Korea, and the United States.

In the U.S., the tick species most often associated with AGS is the lone star tick (Amblyomma americanum) found throughout the South, East and parts of the Midwest. Recent research suggests that the blacklegged tick (Ixodes scapularis and Ixodes pacificus) may also be implicated in alpha-gal syndrome.

The Asian longhorned tick (Haemaphysalis longicornis), the primary trigger of AGS in Asia, has shown up in the US recently, but has yet to be implicated in AGS here. The Cayenne tick (Amblyomma cajennese) found in southern Texas and Florida has also been linked to AGS in Central America, but not yet in the U.S.

While no known pathogen has been linked to triggering AGS, more research is needed to understand the mechanism and the role that ticks play. Currently the thought is that the tick saliva plays a role in activating the allergy to alpha-gal.

Who’s at risk for AGS?

Alpha-gal syndrome is a much more common allergy in the U.S. today than it was a decade ago, with the number of laboratory-confirmed cases growing from 12 in 2009 to over 34,000 in 2019. Unfortunately, AGS has no insurance billing code (ICD code), nor is it a reportable illness to the CDC.

Experts agree alpha-gal syndrome is under-reported in geographic areas where tick bites are common.

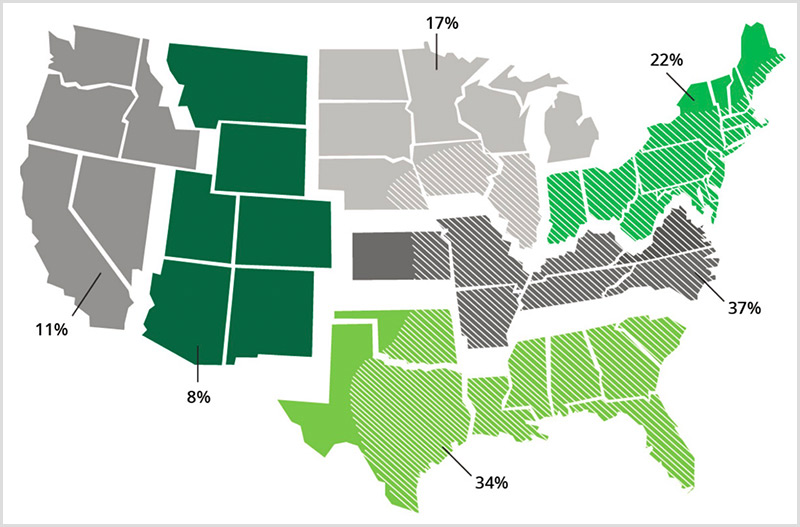

Surveillance for IgE to alpha-gal. Percent positive rates are presented for IgE to alpha-gal within each of six regions in the United States, 2012-2013 (7300 samples). Diagonal white lines on the map represent the known geographic distribution of the lone star tick (Data and map, Viracor-IBT Laboratories; Tick Distribution, CDC).

For now, the biggest risk factor for AGS appears to be repeated bites by ticks that contain alpha-gal in their saliva and salivary glands. It is not understood why, but not everyone who is bitten by a tick containing alpha-gal will develop AGS.

While both children and adults can acquire AGS, most cases have been reported in adults.

Certainly, if a patient with recent tick exposure presents with sudden onset anaphylaxis and recurrent gastrointestinal symptoms, AGS should be considered.

What are the symptoms of alpha-gal syndrome?

The symptoms of alpha-gal syndrome are often delayed, making it much harder to pinpoint the trigger. Someone may wake up at 3 o’clock in the morning in the throes of serious allergic reaction, and have no idea it was brought on by a hamburger they ate the night before.

Symptoms can range from itching and stomach upset to breathing difficulty and full anaphylaxis. AGS reactions often start with itching of the palms of hands and soles of feet.

Common symptoms of AGS include:

- 90% have skin symptoms: itching “pruritus,” flushing “erythema,” hives “urticaria” (swollen, pale red bumps or “wheals” on the skin), angioedema (swelling in deep layers below the skin)

- 60% develop anaphylaxis (a potentially deadly reaction that can restrict breathing)

- 60% have gastrointestinal symptoms (abdominal pain, diarrhea, acid reflux, cramping, vomiting)

- 30-40% experience cardiac symptoms: rapid decrease in blood pressure (hypotension, POTS); palpitations (atypical chest symptoms)

- 30-40% experience respiratory symptoms (wheezing, coughing, shortness of breath)

- 20% of patients will have GI symptoms alone (may present like irritable bowel syndrome)

- 3-5% develop mast cell activation syndrome

- arthritis (rare)

- mouth swelling, sores (rare)

How is AGS diagnosed?

If you experience symptoms after eating mammalian meat products, immediately notify your primary care physician or allergist. Unlike most tick-borne pathogens, the onset of AGS usually takes at least 4-6 weeks from the time of the tick bite. Complicating things further, about a third of patients do not recall a tick bite.

Your doctor should be able to determine if you have AGS based upon your clinical symptoms and a positive blood test: immunoglobulin E (IgE) to the oligosaccharide glactose-alpha-1,3 galactose (alpha-gal.)

In the U.S., Viracor is the main laboratory for AGS testing. The Viracor “specific IgE galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose” test can be taken at most commercial laboratories like Labcorp and Quest and shipped to Viracor.

Warning: The test for alpha-gal is often mistaken for “alpha-galactosidase” or “a-galactosidase A deficiency”—note these are the wrong tests! Because the test is so new, it is recommended to take the proper testing codes with you to the doctor and the laboratory. Click here to download and print a PDF on the proper testing codes for alpha-gal syndrome.

How is Alpha-gal syndrome treated?

There are currently no U.S. FDA-approved medications for the treatment of AGS. As with most allergies, the mainstay of management is avoidance of the allergen. Therefore, the best practice is to avoid exposure to:

- Mammalian meats

- Personal products containing mammalian derivatives

- Medical products containing mammalian proteins, derivatives or parts

- Medications containing mammalian proteins or derivatives

Knowing you must avoid mammalian products is only half the battle, as these products have worked their way into nearly every level of our modern life.

For instance, gelatin is the main ingredient of jellybeans, candy corn, marshmallows, puddings and the capsules of many medications. Chicken and turkey sausages may be stuffed in pork casings, lard (rendered pork fat) is found in many pre-made gravies, sauces, soups, candies, chips, fries, and more.

As with all serious allergies, it is important to have the proper diagnosis and be prepared with how to respond in the event of an emergency. Most allergists will recommend wearing a medical alert bracelet and carrying an EpiPen and an antihistamine with you at all times.

Avoiding alpha-gal hidden components

Mammalian proteins and parts can be found in many medications and medical products. . Because the source of many ingredients is not listed on product labels, your pharmacist may need to contact the manufacturer. Have your pharmacist ask specifically if it contains galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose, alpha-gal, mammalian meat, or any animal by-products.

Common sources of alpha-gal include:

- heart valve replacement derived from pig or cow,

- monoclonal antibodies (cetuximab)

- vaccines (zostavax, MMR and some flu),

- pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy,

- thyroid hormone replacement,

- fillers in medications (magnesium stearate, stearic acid, lactic acid, glycerin, gelatin, lactose)

- antivenom,

- protein powders,

- vaginal capsules

- heparin

Alpha-gal & co-infections

Ticks that carry alpha-gal are known to carry many other pathogens that can be simultaneously transmitted to humans. It is possible to acquire any of these other tick transmitted diseases and also have alpha-gal syndrome. It is also possible to have AGS alone.

The lone star tick, the primary source of AGS in the U.S., is known to transmit the following diseases: human monocytotropic ehrlichiosis (HME), ehrlichiosis (Ehrlichia chaffeensis, Ehrlichia ewingii, and Panola Mountain ehrlichia), Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF), tularemia (Francisella tularensis), Heartland virus, Bourbon virus, Q fever and tick paralysis, as well as Borrelia lonestari, which causes Southern tick-associated rash illness “STARI,” an illness similar to Lyme disease.

With alpha-gal recently discovered in blacklegged ticks, we may also begin to see an increase in AGS in patients with Lyme disease, anaplasmosis, babesiosis, ehrlichiosis, relapsing fever borreliosis, Powassan virus disease, and other diseases transmitted by these ticks.

How to prevent alpha-gal syndrome

For now, the best way to avoid getting AGS is to avoid tick bites. This means wearing tick repellent when working, hiking or playing in grassy or wooded areas where ticks are found. Protecting your pets and doing thorough tick checks after being outdoors is helpful.

If you are bitten by a tick, we suggest following these eight steps.

What to do if you have alpha-gal syndrome?

Learning you have an allergy to all mammalian products can be overwhelming. Because this is such a newly discovered condition there are few resources available.

When it comes to making medical decisions, it’s important to have a knowledgeable provider who understands the risks versus benefits of certain medications and procedures. Vaccines that contain gelatin are one of the riskier products. However, if you need a rabies shot, for instance, you and your doctor may decide that the benefits outweigh the risks and take the necessary steps to mitigate the adverse effects.

To learn more about the history, symptoms and how to diagnose alpha-gal syndrome listen to this interview with Dr. Scott Commins, of the University of North Carolina.

Additional help can be found at:

- Tick-Borne Conditions United

- Alpha-gal Information

- ZeeMaps shows where Alpha-gal is located throughout the world.

- Tick-Encounters, tick identification

- CDC | Alpha-gal allergy

- HHS | Alpha-Gal Syndrome Subcommittee Report to the Tick-Borne Disease Working Group

- Commins SP, Satinover SM, Hosen J, Mozena J, Borish L, Lewis BD, Woodfolk JA, Platts-Mills TA. (2009) Delayed anaphylaxis, angioedema, or urticaria after consumption of red meat in patients with IgE antibodies specific for galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose. J. Allergy and Clin Immunol 123(2):426-33. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.10.052.

- Commins, S. P., James, H. R., Kelly, L. A., Pochan, S. L., Workman, L. J., Perzanowski, M. S., Kocan, K. M., Fahy, J. V., Nganga, L. W., Ronmark, E., Cooper, P. J., & Platts-Mills, T. A. (2011). The relevance of tick bites to the production of IgE antibodies to the mammalian oligosaccharide galactose-α-1,3-galactose. J. Allergy and Clin Immunol, 127(5), 1286–93.e6. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2011.02.019

- Commins SP (2020) Diagnosis & management of alpha-gal syndrome: lessons from 2,500 patients, Expert Review of Clinical Immunology, 16:7, 667-677, DOI: 10.1080/1744666X.2020.1782745

- Fiocchi A, Restani P, Riva E, Qualizza R, Bruni P, Restelli AR, Galli CL. (1995) Meat allergy: I--Specific IgE to BSA and OSA in atopic, beef sensitive children. J Am Coll Nutr. 14(3):239-44. doi: 10.1080/07315724.1995.10718502. PMID: 8586772.

- Hamsten C, Tran TAT, Starkhammar M, Brauner A, Commins SP, Platts-Mills TAE, van Hage M. (2013) Red meat allergy in Sweden: association with tick sensitization and B-negative blood groups. J. Allergy and Clin Immunol. 132(6):1431-1434. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.07.050. Epub 2013 Oct 4. PMID: 24094548; PMCID: PMC4036066.

- Kuehn BM. (2018) Tick Bite Linked to Red Meat Allergy. JAMA. 23;319(4):332. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.20802. PMID: 29362779.

- Mullins RJ, James H, Platts-Mills TA, Commins S.(2012) Relationship between red meat allergy and sensitization to gelatin and galactose-α-1,3-galactose. J. Allergy and Clin Immunol. 129(5):1334-1342.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.02.038. Epub 2012 Apr 3. PMID: 22480538; PMCID: PMC3340561.

- Platts-Mills, TAE, Schuyler, AJ,Commins,SP, et. al ( 2018) Characterizing the Geographic Distribution of the Alpha-gal Syndrome: Relevance to Lone Star Ticks (Amblyomma americanum) and Rickettsia. J. Allergy and Clinical Immun 141;2. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2017.12.470

- Wilson JM, Schuyler AJ, Workman L, Gupta M, James HR, Posthumus J, McGowan EC, Commins SP, Platts-Mills TAE. (2019) Investigation into the α-Gal Syndrome: Characteristics of 261 Children and Adults Reporting Red Meat Allergy. J. Allergy and Clin Immunol Pract. 7(7):2348-2358.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2019.03.031.