MEDICAL DETECTIVE #6: All about Babesia, aka “American malaria”

This article was originally posted on Dr. Richard Horowitz’s Medical Detective Substack. You can find more helpful content by subscribing there.

“American malaria” is spreading in the US (and Europe). It’s what the news is now calling babesiosis, after finding that rates of this tick-borne malarial parasite have been steadily rising in the last few years.

In the journal Open Forum Infectious Diseases, researchers recently found that rates of babesiosis increased an average 9% a year in the US between 2015 and 2022.

Furthermore, 40% of those infected also had other tick-borne illnesses like Lyme disease. Let’s talk about what is happening in our medical practice with not only Babesia, but other infectious illness.

Driving inflammation

For anyone suffering from chronic Lyme disease/PTLDs, there are four potential types of infections that can drive inflammation, resulting in chronic illness. Oftentimes, all four may be present in my patients:

#1 – Bacterial Infections. Patients may have different strains of Borrelia, including relapsing fever Borrelia; multiple strains of Bartonella; as well as exposure to other bacterial tick-borne illnesses including Ehrlichia, Anaplasma, Rickettsial infections like Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (Rickettsia rickettsii), Q fever (Coxiella burnetti), and tularemia (Francisella tularensis).

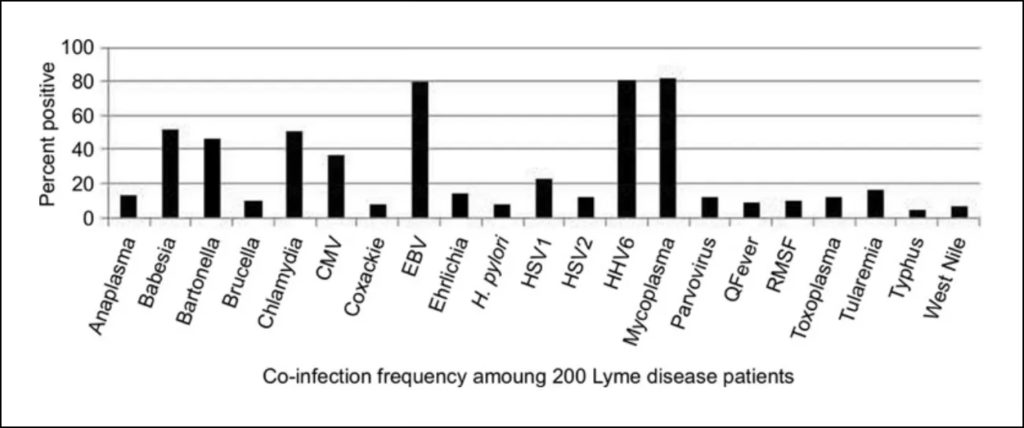

#2 – Viral Infections. Between 10-16% of those individuals living in highly Lyme-endemic areas in the United States have been exposed to the Powassan virus, a tick-borne flavivirus infection. Although most cases do not result in neuroinvasive disease and cause a meningitis (inflammation of the sac surrounding the spinal cord and brain) or encephalitis (inflammation of the brain), other flaviviruses, like Zika or West Nile, are known to be able to persist for long periods of time in the body. When 200 of my patients taking dapsone combination therapy were evaluated in 2018, we found that up to 6.5% had been exposed to West Nile:

From: Horowitz RI, Freeman PR. Precision medicine: retrospective chart review and data analysis of 200 patients on dapsone combination therapy for chronic Lyme disease/post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome: 1. Int J Gen Med. 2019;12:101-119 https://doi.org/10.2147/IJGM.S193608

You can read about the West Nile virus in a recent Medical Detective Substack. Exposure to one flavivirus like West Nile can affect your disease risk for other flavivirus infections like dengue fever.

More research needs to be done on whether the Powassan virus can persist, since its cousin, the Tickborne Encephalitis virus, in Europe has been shown to be able to persist (including in unpasteurized goat milk).

We often find other viral infections where patients may have overlapping long Covid with active coronavirus and/or pieces of the virus in the body increasing inflammation or reactivating the Epstein-Barr virus and Human Herpes Virus 6 virus after exposure to Covid.

This is likely due in part to T cell exhaustion of the immune system, trying to fight COVID, and another reason why you should get your immune system checked from time to time after getting Covid or tick-borne diseases like Lyme and Bartonella, as they can cause immune deficiency.

#3 – Fungal Infections, including candida. Although inhaled fungal infections like histoplasmosis and coccidiomycosis (Valley Fever) are increasing in number and range due to our warming climate (I treated one of my patients with Valley Fever in California last year who had chronic Lyme and Bartonella and is now close to 100% well), the most common fungus that we see is either candida overgrowth in the gut (one the reasons why a very low carbohydrate diet is necessary while on antibiotics for chronic Lyme disease), or mycotoxin illness. This is usually from my patients living in mold-infested buildings, which is also much more common in the last several decades due to hurricanes and flooding.

#4 – Parasitic Infections. When I went to medical school, most of the parasitic infections we were taught involved intestinal parasites like amoeba or giardia or toxoplasmosis (Toxoplasma gondii), affecting an estimated 30–50% of the world’s population.

If I learned about Babesia, a microscopic red blood cell parasite, it was only because it was affecting cattle in Europe (bovine babesiosis), causing cattle fever, due to one of two species of Babesia, Babesia bovis or B. bigemina.

Babesia Makes an Unwelcome Appearance in Dutchess County, NY

We didn’t really hear much about human babesiosis until the late 1970s and early 1980s, when it started to appear on Long Island with a few isolated cases. It certainly was not supposed to be in Dutchess County, NY where I moved to from Queens back in 1987. Babesia first caught my attention back in the mid-to-late 1990s, when we found Babesia microti in both ticks and in my patients.

One woman in her early thirties who’d been in a wheelchair for five years, unable to walk, came to me complaining of drenching night sweats. She was too early for menopause, and after doing a differential diagnostic work-up (the hallmark of a Medical Detective), we ruled her out for other overlapping causes of drenching sweats, such as TB, Non-Hodgkins lymphoma, malaria, hyperthyroidism, Q fever, or Brucella.

Babesiosis was the only likely possibility even though she had not traveled outside Dutchess County, and it was not supposed to exist in our area. We found a positive Babesia test in that patient.

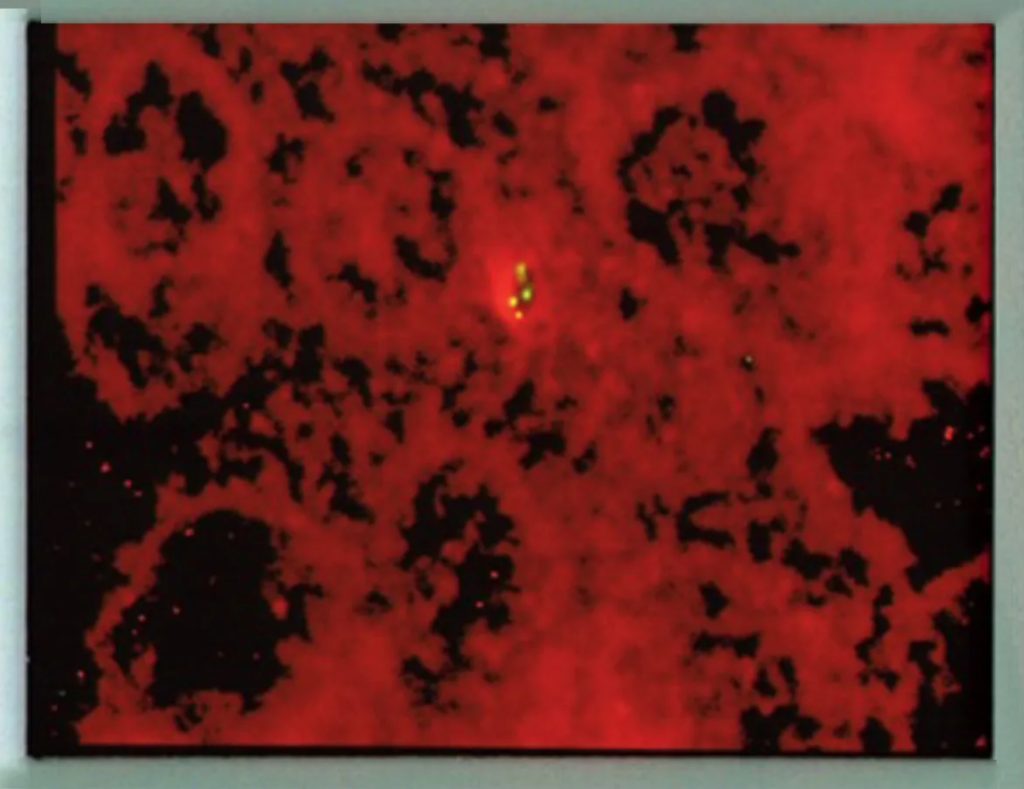

Positive Babesia FISH test, photo provided by Dr Jyotsna Shah, IgeneX laboratory. The Babesia parasite, when positive, is seen fluorescing green under the microscope.

I had just learned about this malarial-like parasite at an LDF International Lyme conference–a good reason to go to Lyme conferences and stay up to date!–and we discovered it by sending out local ticks to have them checked for Babesia, as well as testing our patients by antibody titer and PCR for B. microti.

Many of them came back positive, providing me with one more reason why my chronically ill Lyme patients were staying ill. Sad to say, the insurance companies and local health department did not believe me at the time.

It took several years until I was proven to be correct. I have a whole backstory on that debacle, which I plan to write in a future Substack.

Walking again after Babesia treatment

After we discovered Babesia in my young patient, I gave her Mepron (atovaquone) and azithromycin for 10 days. This was a new treatment regimen for Babesiosis that had not yet been published in the New England Journal of Medicine, which I learned about after discussing her case with Dr. Joe Burrascano. Miraculously, after several months, she began to walk again for the first time after I gave her 10 days of Mepron and Zithromax.

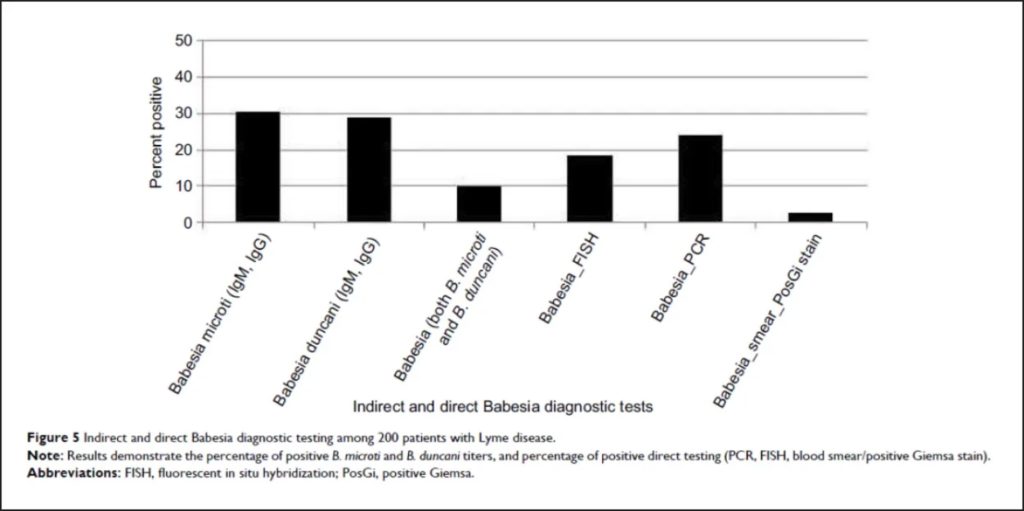

Babesiosis is now found in at least 65% (up to 80% +) of my chronically ill patients who suffer from chronic Lyme disease/PTLDS. Many are infected with Babesia microti, but I’m also finding a significant number of Babesia duncani, a highly resistant red blood cell parasite, in at least 80% of those individuals.

From: Horowitz, R.I.; Freeman, P.R. Precision Medicine: retrospective chart review and data analysis of 200 patients on dapsone combination therapy for chronic Lyme disease/post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome: part 1. International Journal of General Medicine 2019:12 101–119

Symptoms of Babesia

Babesia can be transmitted by a tick bite, blood transfusion, from mother to child with maternal-fetal transmission and/or by solid organ transplantation. Babesiosis in humans can range from an asymptomatic infection to a rapidly fatal disease depending on whether the patient is young, elderly, has an impaired immune system and/or is missing a spleen. Symptoms are typically:

- Malarial-like with low grade fevers (high fevers are possible) and chills (which can be shaking) as well as flushing

- Sweats (day and/or night)

- Muscle pains (myalgia)

- Nausea

- Fatigue that can be accompanied by signs of hemolysis, if the red blood cells break apart. In that case, the patient will often have a high bilirubin, elevated liver functions, low hemoglobin with anemia, and low platelet counts.

- A cough and shortness of breath is also possible.

My patients are screened for Babesia when they fill out the validated Horowitz Lyme symptom questionnaire (HMQ), which can be downloaded from my website: https://cangetbetter.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/MSIDS-QUESTIONNAIRE-FINALR.pdf

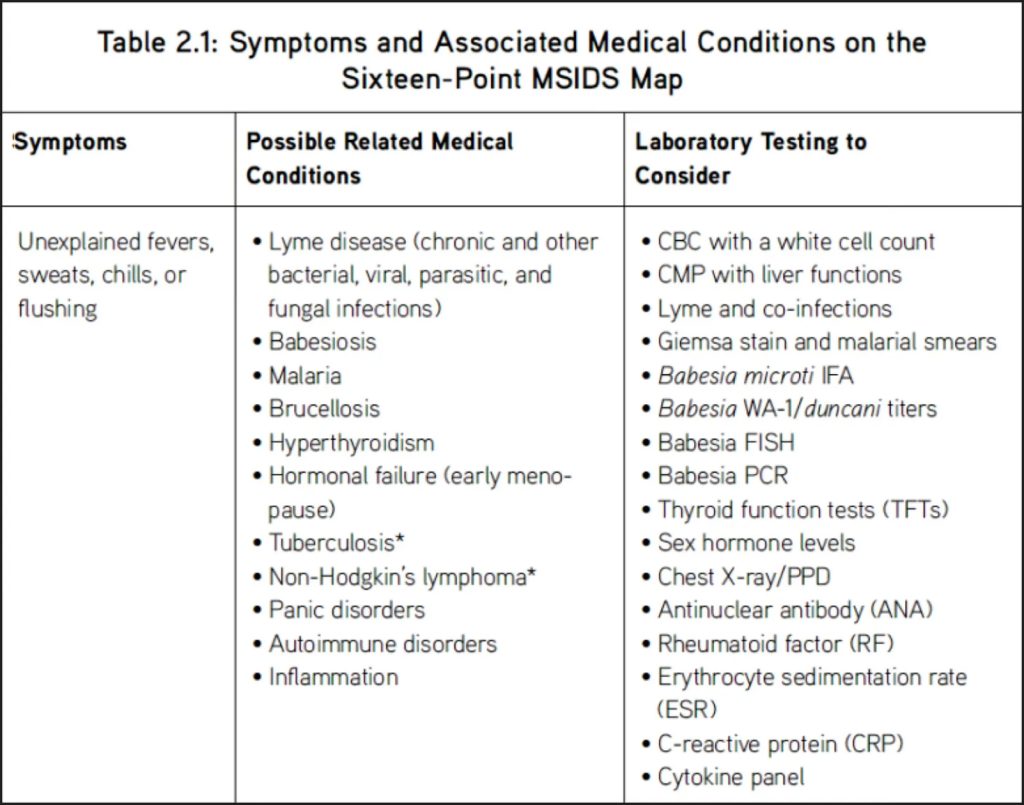

Answering yes to questions 1 and 22 on the questionnaire indicates a possible infection with Babesia, although as mentioned above, anytime a patient has fevers, sweats, chills, flushing, etc, a full differential diagnostic work-up is indicated by the Medical Detective.

Here’s one example of a differential diagnostic work-up for sweats and chills. It’s excerpted from Table 2.1 in my national bestseller, How Can I Get Better? An Action Plan for Treating Resistant Lyme and Chronic Disease, published in 2017.

Most of my patients with Babesia do not have hemolytic anemia. It appears that when the other two Bs are present (Borrelia, Bartonella) hemolysis (red cell destruction) is much less frequent, and different than what you will read about in classical textbook definitions.

This is in part why the Vice Minister of Health of the Chinese government called me years ago to come over and participate in a week-long scientific conference–they were finding Babesia, but it was not following classic textbook appearances. It was a great trip, and I invited Dr. Nick Harris and Dr. Jyotsna Shah from IgeneX to also fly over; they brought their Babesia FISH testing. They proved it was in fact an atypical Babesia strain that was being found in the Chinese patients.

Testing for Babesia

As you read in the first paragraph, Babesia has been spreading over the past several decades in areas where we see other tick-borne disorders. When you go looking for Babesia, it is important to not only do titers for the two major strains in the US (B. microti, B. duncani), but consider that, just as with Lyme and Bartonella, there are many other strains of Babesia that can cause human illness. These include strains like B. divergens in Europe (causing hemolytic anemia) or Babesia divergens-like MO-1 and KO-1 in the US.

I like getting an IgM/IgG Babesia Immunoblot from IgeneX laboratories to check for B. microti and B. duncani, but the reason to order a Babesia FISH test, which uses a fluorescent RNA probe, is that there are over 100 species of Babesia (piroplasms), and although only a few have been identified as causing human infections, the FISH test will pick up the most common species.

We also like using T Labs, which can check for an emerging species of Babesia, B. odocoilei, which was first discovered in Canada, and is occasionally showing up in our resistant patients.

Read more in my next Substack article: Babesia Part II: Emerging Treatments for this highly resistant parasite.

More information on Babesia

When I was co-chair of the “HHS Other Tick-borne Infections and Co-infections” subcommittee, we wrote about Babesia being an emerging tick-borne parasitic infection of interest. You can get more information by reading our report in 2018, and also when I was co-author of the HHS Babesia and Tick-borne Pathogens subcommittee report in 2020:

*https://www.hhs.gov/ash/advisory-committees/tickbornedisease/reports/other-tbds-2018-5-9/index.html

Some of the initial abstracts that I published on Babesia at the International Conferences on Lyme Disease and Other Tick-borne Disorders are listed here:

*Babesiosis in Upstate New York: PCR and RNA Evidence of Co-Infection with Babesia Microti Among Ixodidae Ticks in Dutchess County, NY. Horowitz, R.I., M.D. 12th International Conference on Lyme Disease and Other Spirochetal and Tick-Borne Disorders, April 9-10, 1999. New York, New York

*Atovaquone and Azithromycin Therapy: A New Treatment Protocol for Babesiosis in Co-Infected Lyme Patients. Horowitz, R.I., M.D. 11th International Conference on Lyme Disease and Other Spirochetal and Tick-Borne Disorders, April 25-26, 1998. New York, New York.

Additional References

Empirical Validation of the Horowitz Multiple Systemic Infectious Disease Syndrome Questionnaire for Suspected Lyme Disease. Maryalice Citera, Ph.D., Phyllis R. Freeman2, Ph.D., Richard I. Horowitz2, M.D., International Journal of General Medicine 2017:10 249–273. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28919803

This is part one of a three-part series about Babesia originally published on Substack by Dr. Richard Horowitz. You can read the second and third parts on Substack.

Dr. Richard Horowitz has treated 13,000 Lyme and tick-borne disease patients over the last 40 years and is the best-selling author of How Can I Get Better? and Why Can’t I Get Better? You can subscribe to read more of his work on Substack or join his Lyme-based newsletter for regular insights, tips, and advice.

We invite you to comment on our Facebook page.

Visit LymeDisease.org Facebook Page