Why we need better funding for tick management programs

By Isobel Ronai, Columbia University

Justin Bieber, Shania Twain, Amy Schumer, Avril Lavigne, Ben Stiller and Kelly Osbourne are just six of the millions of people who report that they have suffered from Lyme disease, an illness that costs the U.S. more than $3 billion annually.

Approximately a half-million new cases are added in the U.S. every year.

Much is still unknown about this potentially debilitating illness. Often referred to as the “great imitator,” Lyme disease is a tricky diagnosis because its common symptoms – fevers, chills, headaches and extreme fatigue – are similar to many other chronic diseases.

But one thing is certain: Ticks are the culprit. When they feast on human blood, they transmit the bacterial pathogen that leads to Lyme disease – a pathway similar to how mosquito bites transmit a parasite that causes malaria.

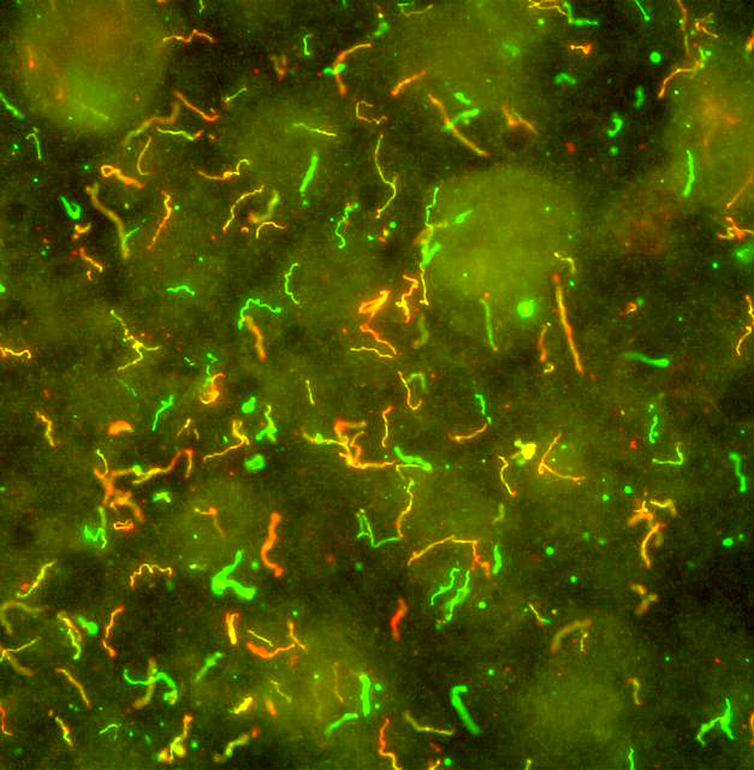

National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID)/CDC

I am a postdoctoral researcher who has dedicated my career to researching ticks and the diseases they cause. Last year, for instance, I discovered that the invasive Asian longhorned tick is unlikely to cause Lyme disease in humans. As I continue to study these organisms, I’m struck by how much remains to be learned.

Why is Lyme disease less common in the US South?

The main tick species that causes Lyme disease – the blacklegged tick – lives across the entire eastern half of the U.S., with Lyme disease hot spots in the Northeast and Midwest. In New York state, up to 40% of ticks may be infected with the bacteria that causes Lyme disease.

But far fewer people seem to get infected with Lyme disease in the southern United States. A possible explanation is that the behavior of the tick when finding a bloodmeal is different in the South, although no one has a good understanding as to why.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

What other diseases do ticks cause?

Lyme disease is not the only tick-borne disease to worry about. Potentially deadly diseases within the U.S. include Rocky Mountain spotted fever in the Southeast, and Powassan virus disease in the Northeast and Great Lakes region. Outside the U.S., there is tick-borne encephalitis and Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever, which has a fatality rate of up to 40%. And there are others.

Even when they don’t transmit pathogens to humans, the saliva of ticks themselves can also directly cause disease, including alpha-gal syndrome, which leads to a potentially deadly allergy to foods such as red meat. It is most common in the Southeast, and its incidence is increasing.

Ticks can also transmit multiple pathogens – viruses, bacteria or parasites – in a single bite. As many as 28% of ticks are infected with two or more pathogens. Researchers don’t yet fully understand how these co-infections affect people, but they can have a more severe impact on the human immune system than an infection from a single pathogen.

CDC/ Dr. Gary Alpert/Urban Pests/Integrated Pest Management (IPM)

The underfunding of tick research

In just the past 20 years, seven new tick-borne diseases have been discovered in the U.S. Yet many more are likely to be identified with increased research effort and funding.

And therein lies the problem: Tick research has long been underfunded worldwide. The U.S. spends just $63 per estimated Lyme disease case annually in terms of research dollars, which totaled only $40 million in 2020.

Right now, tick control strategies are still in their infancy. More efforts are needed to identify why and where tick populations are increasing and to develop ways to eradicate them. Based on a recent study of public health and vector control programs, only 12% report having funded tick control.

Long-term management programs that are evidence-based and modeled after the successful U.S. malaria-eradication management program would work best for controlling ticks.

There has been some progress recently. In 2020, a landmark national plan from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention identified five goals for preventing vector-borne diseases in humans, including Lyme disease. A national strategy is also being developed to combat these diseases; that report will be submitted to Congress in 2023. The top priority identified so far is the need for more research.

How can I help prevent tick-borne diseases?

If you are in an area that has ticks, you can take steps to protect yourself from a tick bite. First, remember that the riskiest time for bites is during spring and summer. Be mindful when in places where ticks hang out, like wooded and grassy areas – and remember that “grassy areas” include your yard. Wear enclosed shoes with socks over long pants, apply a pesticide containing permethrin to your clothing and use a tick repellent like DEET.

When you go back inside, do a full body check for ticks. Check pets too. Change your clothes – tumble drying at high temperatures kills ticks – and shower.

And if you spot a tick, remove it immediately. The less time a tick feeds on you, the lower the chance it will transmit a pathogen that will make you sick.

Isobel Ronai is a postdoctoral researcher at Columbia University.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

We invite you to comment on our Facebook page.

Visit LymeDisease.org Facebook Page