Our testimony asking Congress to boost Lyme disease funding

LymeDisease.org submitted written testimony last month to Congress, asking for Lyme disease funding to be increased to $202 million.

Here’s what we said:

Submitted by: Phyllis Mervine, President and Founder, LymeDisease.org

Prepared for: House Committee on Appropriations, Subcommittee on Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies

Addressing: Dept. of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Request for Increased Research Funding: Lyme disease is the number one reported vector-borne disease (VBD) in the United States. According to CDC surveillance data, 36,429 cases were reported in 2016 compared to 96,075 total cases of VBD. (CDC MMWR 2018) But while Lyme disease accounts for 38% of the total case counts for VBDs, it receives only 4% of the funding allotted to VBDs: $21M compared to $534M for VBDs. (NIH Funding Estimates 2018)

Recommendation: Increase Lyme disease funding to $202M, commensurate with the fact that Lyme disease represents 38% of the total disease burden for VBDs.

Introduction

For over 30 years LymeDisease.org has represented Lyme disease patients. The non-profit advocacy organization is highly respected and has earned a reputation as one of the most trusted sources of information in the community. Our website draws over 3 million unique visitors a year. We have also conducted and published patient surveys in peer-reviewed journals. In 2015, we launched the first national Lyme disease patient registry and research platform, MyLymeData, which has to date enrolled over 12,000 patients.

Lyme disease, caused by the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi and transmitted via tick bite, is the most common VBD in the United States. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that 300,000 new cases of Lyme disease occur annually (CDC 2013).

The CDC surveillance case definition captures roughly 30,000 cases per year, which the CDC acknowledges greatly underrepresent the actual incidence of the disease. Since the late 1990s, the number of reported cases has tripled and Lyme disease is now reported from every state.

Although most patients who are diagnosed and treated early are restored to health, treatment failures ranging from 10% to 35% have been reported. Many patients are not diagnosed until later in the disease when treatment success is much harder to achieve (Asch 1994, Aucott 2013, Johnson 2018, Shadick 1994, Shadick 1998, Treib 1998). Aucott found that even with early diagnosis and treatment, roughly 35% developed new-onset fatigue, 20% widespread pain, and 45% neurocognitive difficulties at six months after treatment. (Aucott 2013)

The majority of patients in our published survey of over 3,000 reported being ill for 10 or more years. (Johnson 2014) In a 2018 study, more than half (51%) the patients with late/chronic Lyme disease reported that it took them more than three years to be diagnosed and roughly the same proportion (54%) saw 5 or more clinicians before diagnosis. (Johnson 2018)

Patients with late/chronic Lyme disease report having a quality of life that is significantly worse compared to the general population and people with multiple sclerosis, diabetes, and congestive heart failure. (Johnson 2014, Klempner 2001).

In a recent survey of over 3,000 patients, a majority (65%) reported their health status as fair or poor. (Johnson 2018) Moreover, 32% reported their work status as disabled (whether or not receiving disability payments).

Plagued by perennial underfunding

In the 40 years since the discovery of the causative spirochete, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) has funded only 3 research studies on the retreatment of chronic Lyme disease, the last trial being funded over 15 years ago (Fallon 2008, Klempner 2001, Krupp 2003).

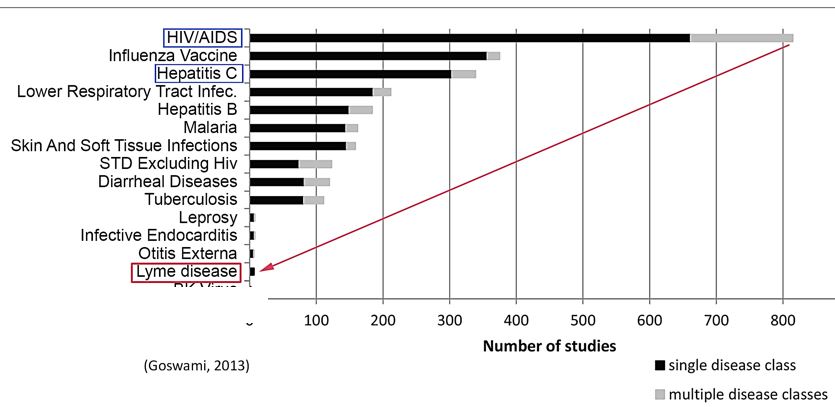

Although the incidence of Lyme disease (300,000) is nearly 8 times higher than the number of people diagnosed with HIV/AIDS each year in the US (38,500), the number of clinical studies for Lyme disease trails behind leprosy, which has an incidence of fewer than 200 cases a year. (CDC 2016, Health Resources and Services Administration).

This is illustrated in the figure below, derived from a study by Goswami on clinical trials for infectious diseases listed on ClinicalTrials.gov. (Goswami 2013)

In their 2018 report to Congress, the Tick-Borne Diseases Working Group (TBDWG), a federal advisory panel established under the 21st Century Cures Act passed in 2016, urgently recommends increasing federal funding for Lyme disease and protests the government’s failure to keep pace with the growing public health threat:

Federal funding for tick-borne diseases is less per new surveillance case than that of other diseases. The U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) and CDC spend $77,355 and $20,293, respectively, per new surveillance case of HIV/AIDS, and $36,063 and $11,459 per new case of hepatitis C virus, yet only $768 and $302 for each new case of Lyme disease [emphasis added]. Federal funding for tick-borne diseases today is orders of magnitude lower, compared to other public health threats, and it has failed to increase as the problem has grown. [TBDWG Report 2018]

Costs significant

The total costs of Lyme disease consist of both the costs of early and late/ chronic Lyme disease. We take the annual incidence of new acute cases from the CDC 300,000 surveillance estimate.

The number of patients with chronic or persistent Lyme disease is unknown, but we may estimate it based on the stage of the disease at diagnosis and the percentage of treatment failures associated with that stage. Treatment failures ranging from 10-35% have been reported in early disease and higher rates are reported for late disease.

The prevalence of late/chronic Lyme disease is a cumulative number that grows annually and is diminished only by death or cure.(Johnson 2014) We may assume treatment failure rates ranging from 10% to 50%, given the 10-35% treatment failure rates for early Lyme disease and the higher treatment failure rates for those diagnosed late. We may then use the percentage of patients who fail treatment to estimate the cumulative number of those who remain ill over time.

Assuming that between 35% and 50% remain ill after treatment and the duration of their illness lasts between 10 and 20 years, cases of late/chronic Lyme disease would range from 1-3M.

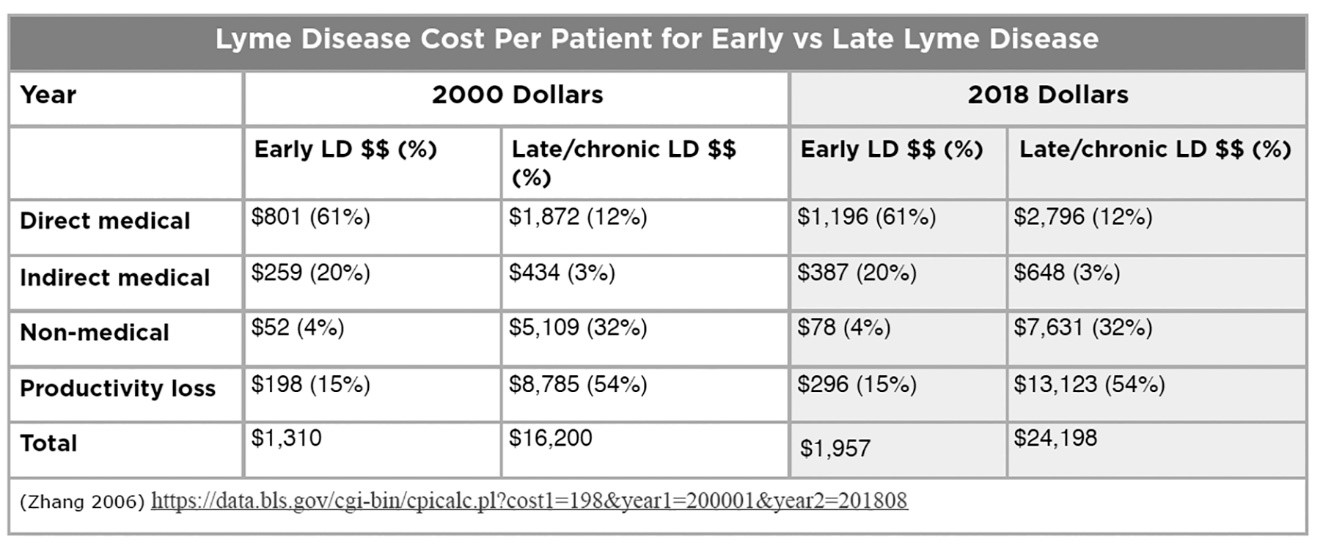

In his 2006 study, Dr. X. Zhang of the CDC estimated the total cost of Lyme disease at $203M, based on the estimate of Lyme cases at that time–approximately 24,000 surveillance cases a year. (Zhang 2006) He included direct medical costs, indirect medical costs (e.g. additional out-of-pocket medications), other costs (e.g. travel), and costs due to loss of productivity (e.g. lost work days).

Zhang found that the cost of treating late/chronic Lyme disease is over 12 times higher than the cost of treating early Lyme disease. He found that loss of work productivity and non-medical costs were over 85% of the cost of late Lyme disease, more than cost of treatment.

With the CDC’s increased estimate of annual Lyme cases (from 30,000 to 300,000 in 2013) as well as adjustment for inflation, Zhang’s estimated cost of illness has increased substantially as reflected in the table above. Assuming the 1-3M prevalence rate of late/chronic Lyme disease described above at a cost of $24,198 per case based on Zhang’s study (as adjusted for current CDC case estimates and inflation), the total cost for late/chronic Lyme disease falls roughly between $24B and $72B.

We base the cost of acute Lyme disease on a more recent Johns Hopkins study by Adrion, who found direct medical costs alone to be $2,968 higher for patients with early Lyme disease than patients generally. Adrion’s study concluded that direct medical costs for early Lyme disease alone may be as high as $1.3B a year.

Assuming the same indirect medical costs, non-medical cost and productivity loss percentages as Zhang would increase the annual cost of early Lyme disease in the study by 39% to $4,125 per patient or $1.8B per year.

When the total costs (direct medical, indirect medical, non-medical, and loss of productivity costs) of acute ($1.8B) and late/ chronic Lyme disease are combined, they aggregate to between $25.8B to $73.8B.

Conclusion: Lyme disease represents a significant and growing burden of disease in the United States. A large number of patients are diagnosed late and/or remain ill after short term treatments fail to cure them. The quality of life burden on patients with late/chronic Lyme disease exceeds that of most other diseases.

Accordingly, funding for Lyme disease needs to be increased to $202M, to be commensurate with the fact that it represents 38% of the total disease burden for VBDs.

Thank you for the opportunity to submit testimony.

Phyllis Mervine, President and Founder

LymeDisease.org

PO Box 716

San Ramon CA 94583

References

Adrion ER, et al. Health care costs, utilization and patterns of care following Lyme disease. PLoS ONE, 2015. 10(2): p. e0116767.

Asch ES, et al. Lyme disease: an infectious and postinfectious syndrome. J Rheumatol, 1994. 21(3): p. 454-61.

Aucott JN, Rebman, AW. Crowder, L.A.; Kortte, K.B. Post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome symptomatology and the impact on life functioning: Is there something here? Qual. Life Res. 2013, 22, 75–84.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Provides Estimate of Americans Diagnosed with Lyme Disease Each Year. 2013. Available online: http://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2013/p0819-lyme-disease.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC provides estimate of Americans diagnosed with Lyme disease each year. Press Release 2013; Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2013/p0819-lyme-disease.html.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report. 2016; Volume 28. Available online: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html .

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Lyme Disease: Data and Surveillance. https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/datasurveillance/index.html.

Fallon BA,et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of repeated iv antibiotic therapy for Lyme encephalopathy. Neurology 2008, 70, 992–1003.

Goswami ND, et al. The state of infectious diseases clinical trials: A systematic review of clinicaltrials.Gov. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e77086.

Health Resources and Services Administration. National Hansen’s Disease (Leprosy) Program Caring and Curing Since 1894. Available online: https://www.hrsa.gov/hansens-disease/index.html.

Johnson L, et al. Severity of chronic Lyme disease compared to other chronic conditions: a quality of life survey. PeerJ, 2014. 2, e322 DOI: 10.7717/peerj.322.

Johnson L. TBDWG July 24, 2018 – Written Public Comment. Available online: https://www.hhs.gov/ash/advisory-committees/tickbornedisease/meetings/2018-07-24/written-public-comment/index.html

Klempner M, et al. Two controlled trials of antibiotic treatment in patients with persistent symptoms and a history of Lyme disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 345, 85–92.

Krupp LB, et al. Study and treatment of post Lyme disease (Stop-LD): A randomized double masked clinical trial. Neurology 2003, 60, 1923–1930.

McGinty J. Lyme Disease: An Even Bigger Threat Than You Think A look at why cases of the tick-borne illness are undercounted, in Wall Street Journal. June 22, 2018.

Shadick NA, et al. The long-term clinical outcomes of Lyme disease. A population-based retrospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med, 1994. 121, 560-7.

Shadick NA, et al. Musculoskeletal and neurologic outcomes in patients with previously treated Lyme disease. Ann Intern Med, 1999. 131(12): p. 919-26.

Shadic, NA, et al. The long-term clinical outcomes of Lyme disease. A population-based retrospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med, 1994. 121(8): p. 560-7.

Tick-Borne Disease Working Group 2018 Report to Congress. Available online: https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/tbdwg-report-to-congress-2018.pdf

Treib J, et al. Clinical and serologic follow-up in patients with neuroborreliosis. Neurology, 1998. 51(5): p. 1489-91.

Zhang X, et al. Economic impact of Lyme disease. Emerg Infect Dis, 2006. 12(4): p. 653-60.

We invite you to comment on our Facebook page.

Visit LymeDisease.org Facebook Page