Designing an environment for those “displaced” by Lyme disease

by Sylvia Janicki

On a balmy early-summer day in 2014, in the bucolic Mississippi countryside, I found a tick burrowed into the side of my right leg. Shortly after, a bull’s-eye rash formed around the tick-bite, and then I fell ill, developing flu-like symptoms, muscle and joint pain, and headaches, among other symptoms.

I would later learn that I had contracted Lyme disease. Despite medical treatment, I have experienced pain, discomfort, and fatigue almost every day since that moment over four years ago.

As a landscape architect living with the daily challenges of chronic illness, I became interested in understanding the relationship between illness and place. How can we transform or design our environment to support the needs of people living with chronic illnesses like Lyme disease?

THE IMPORTANCE OF PLACE

Research on vector-borne disease re-emergence indicates landscape change as the primary catalyst of disease transmission. Yet many studies have also demonstrated the potential of our environment in promoting public health and wellbeing.

For people living with chronic illnesses like Lyme disease, where modern medicine provides limited relief, our surrounding environment presents an even greater potential as a source of healing. Effects of environmental factors on psychological wellbeing and lifestyle-induced health conditions such as heart disease and diabetes are commonly recognized in design and planning professions.

However, there has been little to no research on the experience of place and the environmental needs of those living with chronic illnesses and invisible disabilities such as the debilitating chronic conditions brought on by Lyme disease. Without understanding the experience of illness, we cannot design effective healing environments.

CHRONIC ILLNESS AND DISPLACEMENT

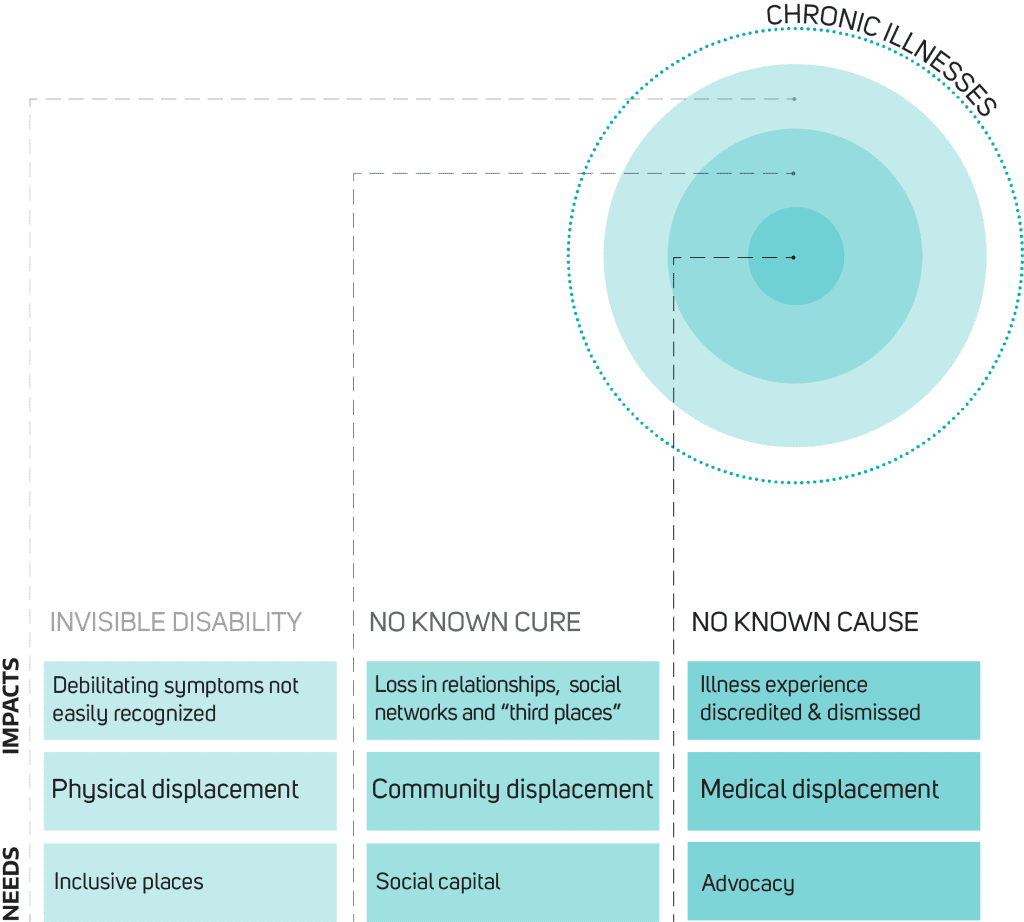

To begin to explore this question, I interviewed several individuals who live with Lyme disease, to understand how their illness affects the way they navigate and experience place. The interviews revealed that living with a chronic illness like Lyme disease can come with different forms of displacement, in both literal and metaphorical terms, ranging from physical exclusion to social isolation and emotional loss.

Additionally, many people described experiencing a form of medical displacement in which they felt that their illness is often overlooked or dismissed by healthcare providers. Creating more supportive environments for people with Lyme disease means that, as a first step, these different forms of displacement need to be identified and addressed.

PHYSICAL DISPLACEMENT

In the most literal sense, living with debilitating symptoms of Lyme disease can result in physical exclusion from places, even if, and sometimes especially because the experience is invisible.

For example, places with stimulating triggers such as noise, scents and bright lights may deter those with increased environmental sensitivities. Places without universal access or comfortable and frequent seating may discourage those with exacerbated pain or fatigue.

Furthermore, different means of transportation can present unique challenges to people dealing with various symptoms of the illness. Walking and biking can be difficult for those who suffer from post-exertion malaise; neurological symptoms may limit the ability of people to drive; and taking mass transit can provoke anxiety, with the unpredictable onset of symptoms.

As one interview participant stated: “I don’t take public transit, especially by myself. I’m afraid of collapsing.” These limitations lead to a loss in mobility that results in even greater spatial confinement.

As a result, most people living with chronic illnesses like Lyme disease spend a lot more time in their own homes, where they are most able to control their immediate surroundings. But even with a greater need for and dependence on a safe home environment, people with Lyme disease often face significant challenges in finding safe housing because of the limitations their illness poses.

One person described her experience like this: “Every year I’ve been moving…my last place was mold-free, but then we started getting chemicals coming through the vents from upstairs.”

Though chronic illness results in many competing needs and compromises, there is little institutional support for such invisible disabilities. Most people can only resort to trial and error to figure out where they can live comfortably.

Another interviewee expressed a common sentiment: “There is no way to get safe housing in a formal way. I keep ending up in these situations where I can’t find a safe place to live.”

COMMUNITY DISPLACEMENT

The physical displacement faced by people living with complex symptoms of Lyme disease can lead to a loss in community relationships, as the illness tends to last for a long time and forces permanent changes upon the daily life of the sufferer.

Persistent, debilitating and unpredictable symptoms can limit people’s ability to travel, work, and play. Thus, most people lose what have been called “third places” in their lives – places other than home and workplace, where they can socialize and interact with others. Consequently, they lose not only the spaces themselves but the activities, interactions, and shared experiences that come with them.

As one person described: “I’ve not done a lot of things in the last 27 years. You avoid going to events, crowded places and noisy places. You don’t interact with your friends and family as much.”

Over time, living with a chronic illness becomes extremely isolating: from being more physically confined, from the resulting loss in social relationships, and from the lonely feeling of having to deal with illness in solitude because others don’t understand.

One person exclaimed: “It’s hard if I can’t reciprocate… I try to build community, but I just don’t have the energy for it. It’s just hard. It’s hard to make new friends and it’s hard to sustain friendships.”

These changes can lead to emotional reactions and feelings of grief with a loss of self-identity: “It’s a big loss, [not being able to be] active and sharing that activity with people. It’s like okay… what am I going to share now?”

MEDICAL DISPLACEMENT

Besides losing places and community, people living with Lyme disease often experience a medical displacement as well, leaving many people feeling invalidated in their illness experience. Many chronic Lyme disease patients are accused of being hypochondriacs because their illness is not visible to others, including medical professionals.

In the interviews, several people described their convoluted medical journeys. Said one: “We went to a lot of doctors – neurologists, primary care, specialists. They all said – everything’s fine. She’s healthy.”

In some cases, such dismissals bring a sense belittlement and judgment: “This one neurologist told me that I should take a vacation. He said – you’re perfectly fine, you should go on a vacation and lighten up your mood.”

The negative responses from medical practitioners and the lack of answers that accompany worsening symptoms can all lead to an increased sense of loss, confusion, frustration and anxiety. As one woman put it: “I thought I was crazy… It’s very mysterious. I was stuck in bed for a few months.”

HEALING THROUGH SPACE

Perhaps it is not surprising that chronic Lyme disease patients have reported suffering a lower quality of life compared to individuals living with most other chronic diseases, including those with congestive heart failure, strokes, and multiple sclerosis.

In one survey, 72% of Lyme disease patients reported having fair or poor health. The same survey also found that 75% of Lyme patients experience severe or very severe symptoms on a daily basis.

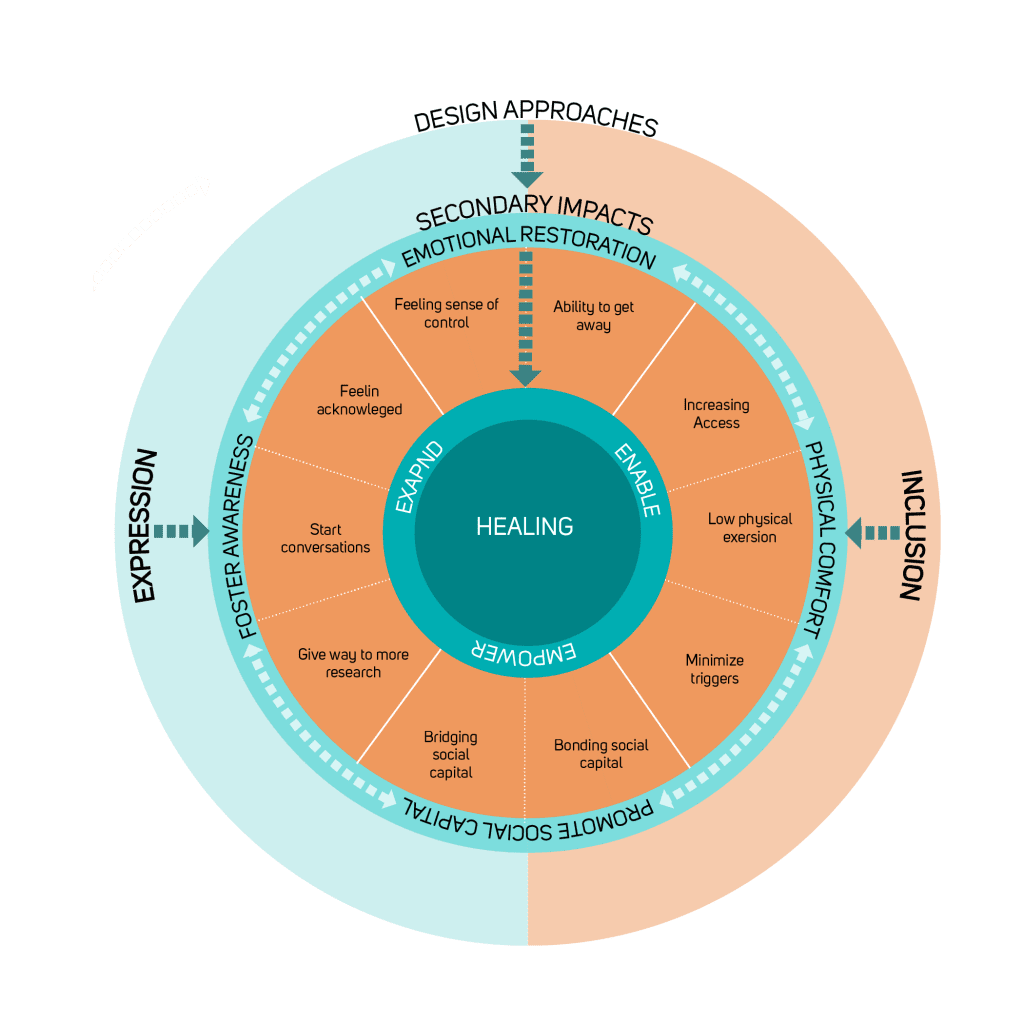

Considering the complex physical, emotional, and social impacts resulting from chronic illness, spatial designers should find ways to allow people with different physical and emotional needs to use and occupy spaces comfortably.

Designers should also consider how to help reduce the isolation of living with a chronic illness.

Expanding their everyday geography will allow such people to participate in more activities, support their independence, and empower them to make their own choices in life.

References

- Patz, J. A., Daszak, P., Tabor, G. M., Aguirre, A. A., Pearl, M., Epstein, J., … Zakarov, V. (2004). Unhealthy Landscapes: Policy Recommendations on Land Use Change and Infectious Disease Emergence. Environmental Health Perspectives, 112(10), 1092–1098. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.6877

- Johnson, L., Wilcox, S., Mankoff, J., & Stricker, R. B. (2014). Severity of chronic Lyme disease compared to other chronic conditions: a quality of life survey. PeerJ, 2, e322. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.322

We invite you to comment on our Facebook page.

Visit LymeDisease.org Facebook Page