LYME SCI: North America is “ground zero” for babesiosis

A group of international researchers recently published “Emerging Human Babesiosis with ‘Ground Zero’ in North America.” Their review offers important perspective on this emerging illness.

Although human babesiosis has been confirmed on every continent except Antarctica, North America accounts for more than 95% of all cases worldwide.

The United States has reported more than 20,000 cases since 2006. In North America, Babesia microti and B. duncani are the primary causes of human babesiosis.

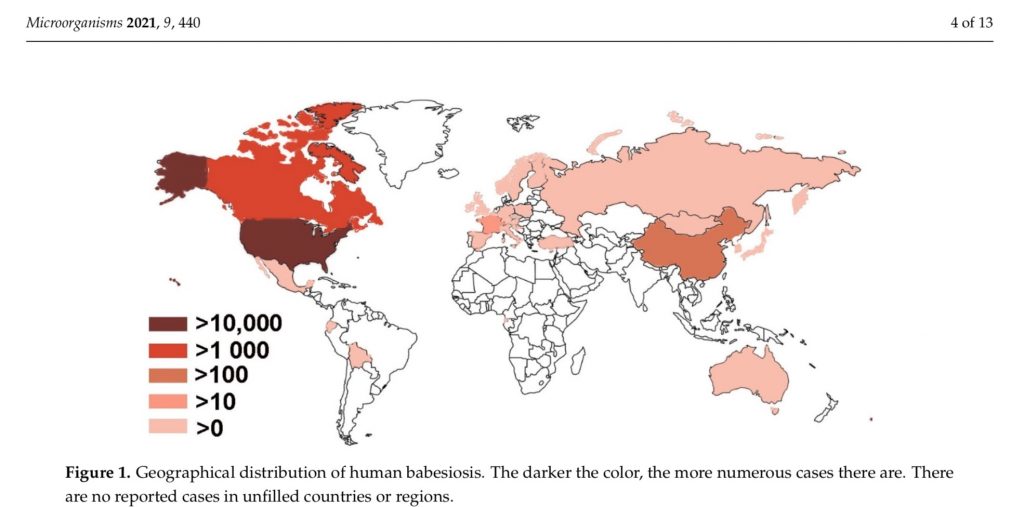

Geographical distribution of human babesiosis

Babesiosis is considered an emerging infectious disease, with the first human case reported in 1957. While it has increased exponentially in the US since the 1980s, it wasn’t until 2011 that babesiosis became a nationally notifiable disease. (Those are illnesses that are reported to the CDC.)

Babesia is a malaria-like parasite, also known as a “piroplasm,” that is specific to various vertebrate animals. For instance, Babesia canis infects dogs. Some species of Babesia are zoonotic, meaning they can be transmitted from animal to human.

Out of the hundreds of Babesia (B.) species reported worldwide, the only ones confirmed to infect humans are B. microti (northeastern & midwestern U.S.), B. divergens (Europe), B. venatorum (China & Europe), B. duncani (U.S. Pacific Coast), B. crassa (China), a new agent designated MO1 (detected in Missouri), and two as yet unnamed species.

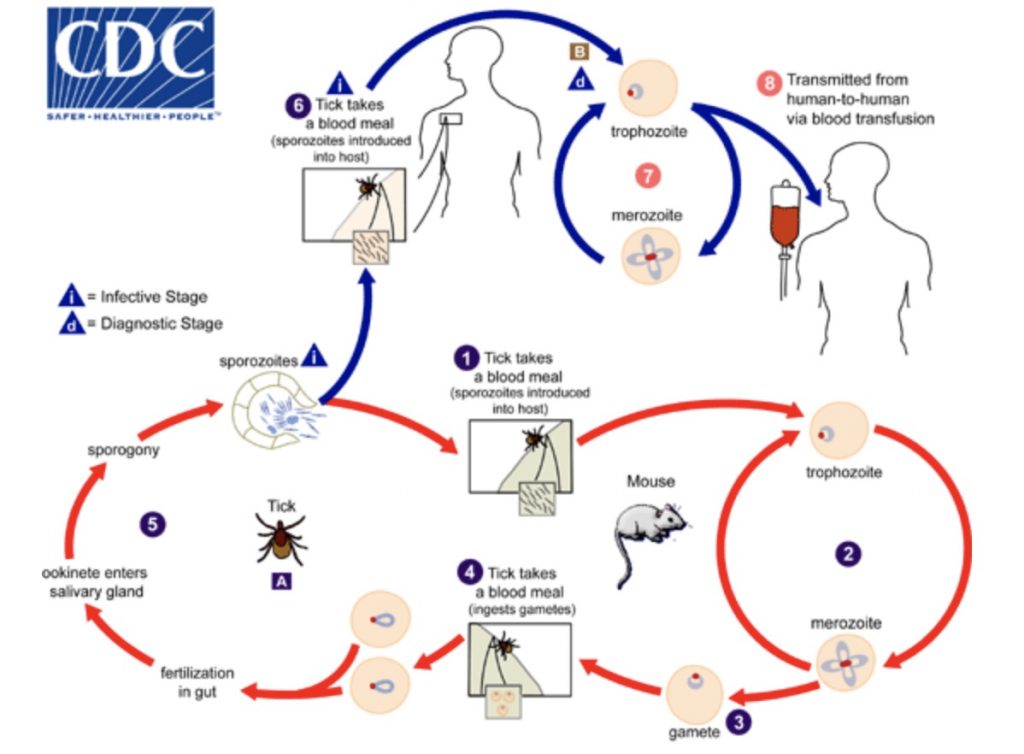

All Babesia require hardbodied (Ixodes) ticks in their life cycle as well as a vertebrate reservoir host (e.g. mice, vole, deer).

In North America, the blacklegged tick (Ixodes scapularis) is the primary vector for B. microti in the East. The winter tick (Dermacentor albipictus) is a vector for B. duncani along the West coast. The majority of Babesia is transmitted by nymphal ticks peaking during the warmer months.

Transmission

The blacklegged tick is also known to carry and transmit several other infectious diseases to humans including Lyme disease, anaplasmosis, ehrlichiosis, Powassan virus disease and Borrelia miyamotoi disease. Because ticks can transmit more than one pathogen in a single bite, a person can be simultaneously infected with more t,han one tick-borne disease.

Patients who are co-infected with Lyme disease and babesiosis tend to be much sicker that those who are infected with either single pathogen. According to MyLymeData, 44% of the patients with Lyme disease report Babesia as a co-infection.

The authors of the “Ground Zero” study mention several factors contributing to the large number of cases in the US. A major one is that babesiosis is a reportable disease here while it is not reportable in many other parts of the world.

Infection by tick is the most common method of contracting babesiosis. According to the CDC, it can also be transmitted from an infected mother to her baby during pregnancy or delivery.

Blood transfusion is another route of infection. The FDA estimates blood transfusion from Babesia-infected donors account for up to 38% of fatalities linked to transfusion related deaths. (No tests have been licensed yet for screening blood donors for Babesia.)

Symptoms of babesiosis

Similar to malaria, Babesia parasites infect, grow and reproduce in the red blood cells. The symptoms can vary from mild to severely painful viral-like illness to death. Since it can take up to six weeks for symptoms to develop, many people don’t associate the illness with a tick bite.

Common symptoms include:

- High fever

- Chills

- Sweats

- Headache

- Muscle, joint or body aches, and pain

- Nausea

- Loss of appetite

- Fatigue

- Feeling short of breath “air hunger”

Babesiosis can be life-threatening in people who have a weakened immune system (cancer, lymphoma, HIV, AIDS, liver or kidney disease or people who have no spleen.)

Complications can include:

- Anemia (hemolysis)

- Low platelet count (thrombocytopenia)

- Low and unstable blood pressure

- Blood clots and bleeding (disseminated intravascular coagulation)

- Malfunction of vital organs (kidneys, lungs, liver)

- Death

Diagnosing babesiosis

The diagnosis of babesiosis is often missed because many of the symptoms are nonspecific. The CDC says a suspicion of babesiosis should be considered if the routine blood work shows “hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia. Additional findings may include proteinuria, hemoglobinuria and elevated levels of liver enzymes, blood urea nitrogen and creatine.”

The diagnosis requires a manual review of a blood smear by microscopy, and/or a FISH (fluorescent in-situ hybridization) test that detects live parasites by rRNA.

LymeSci is written by Lonnie Marcum, a Licensed Physical Therapist and mother of a daughter with Lyme. In 2019-2020, she served on a subcommittee of the federal Tick-Borne Disease Working Group. Follow her on Twitter: @LonnieRhea Email her at: lmarcum@lymedisease.org .

References

Yang,Y.;Christie,J.;Köster, L.; Du, A.; Yao, C. (2021) Emerging Human Babesiosis with “Ground Zero” in North America. Microorganisms DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms9020440

CDC – Babesiosis https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/babesiosis/

We invite you to comment on our Facebook page.

Visit LymeDisease.org Facebook Page