LYME SCI: “Super-fast” lone star ticks are showing up in new places

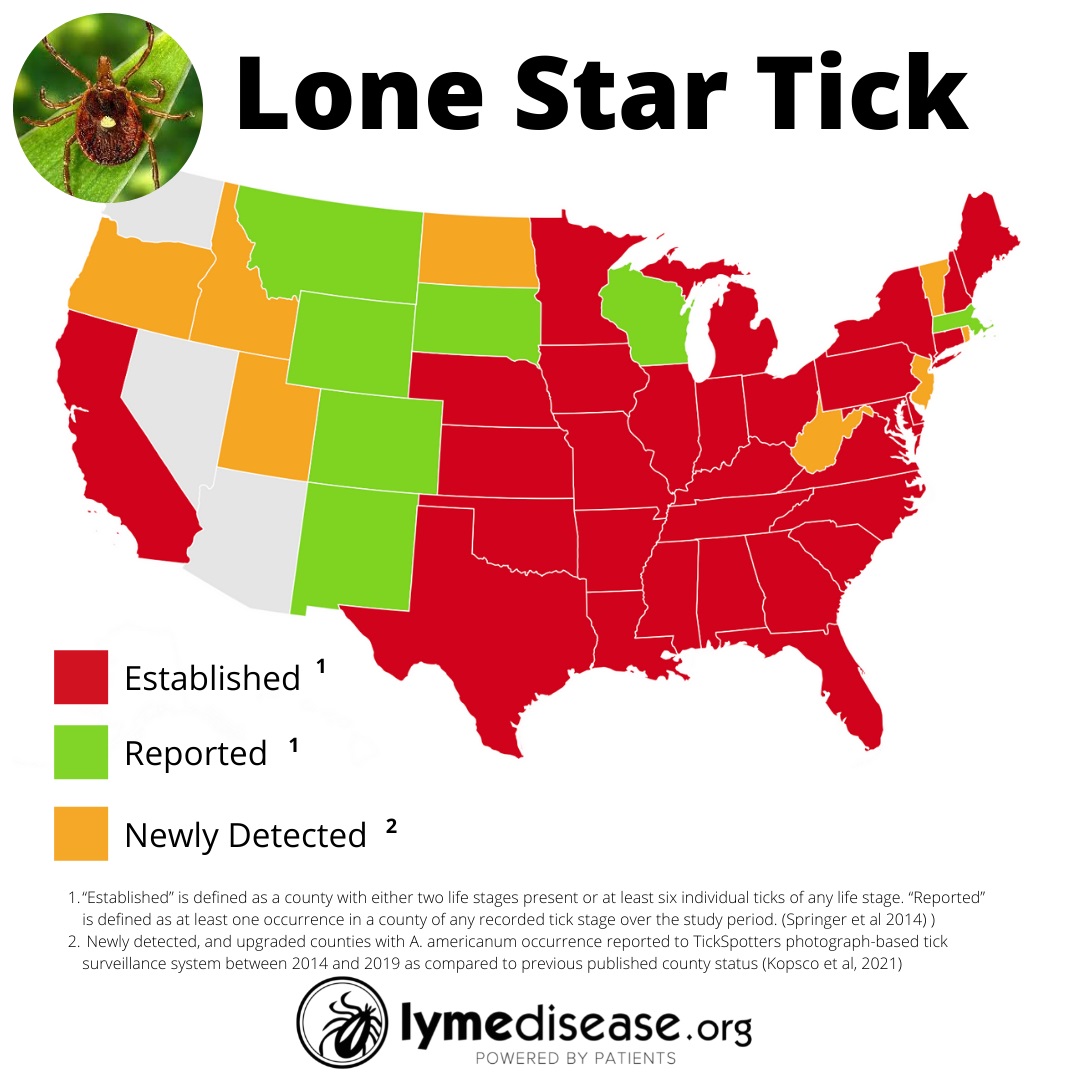

The lone star tick (Amblyomma americanum) has been rapidly expanding its range, from the Southern United States into the Northeast and Midwest.

This tick is a major vector of several viral, bacterial, and protozoan pathogens affecting humans, pets, livestock, birds and other wild animals in the United States. In some Midwestern states, it is commonly known as the “turkey tick” due to its association with wild turkeys. (Childs and Paddock, 2003)

Currently, the lone star tick is known to transmit human ehrlichiosis, tularemia, Heartland virus, Bourbon virus, Southern tick-associated rash illness (STARI) and rarely Rocky Mountain spotted fever—one of the deadliest tick-borne diseases in the US.

People bitten by a lone star tick may also develop alpha-gal syndrome—a severe allergy to meat and meat-related products.

A recent crowdsourced science project has documented the largest increase of the lone star tick in decades. Researchers documented new tick encounters in over 300 counties—including six new counties in western states—where these ticks had not been documented before.

TickSpotters program evaluates photos

In a study published in the Journal of Medical Entomology, researchers at the University of Rhode Island (URI) evaluated over 9,500 photos submitted between 2014-2019 to the TickSpotters surveillance program.

To document the changes, researchers first identified the ticks in the submitted photos, then logged the county each was reported from. They used this method to plot the geographic ranges of three medically important U.S. tick species: Amblyomma americanum, Ixodes scapularis and Ixodes pacificus. The last two are the vectors for Lyme disease.

More than 5,000 photographs of the lone star tick were received from over 1,000 counties across the US. Of those, 341 counties had no previous record of lone star ticks. The largest expansion of the lone star tick was seen in Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, and Ohio.

In addition, the lone star tick was reported in several counties in the western US, a region not typically associated with these ticks. Notably, it was found in six new counties in California, four counties in Colorado and one new county each in Idaho, Oregon and Utah.

“The causative drivers of these upturns are complex, but have a lot to do with increased host availability, warming temperatures, and moisture availability,” researcher Heather L Kopsco, PhD, told Entomology Today,

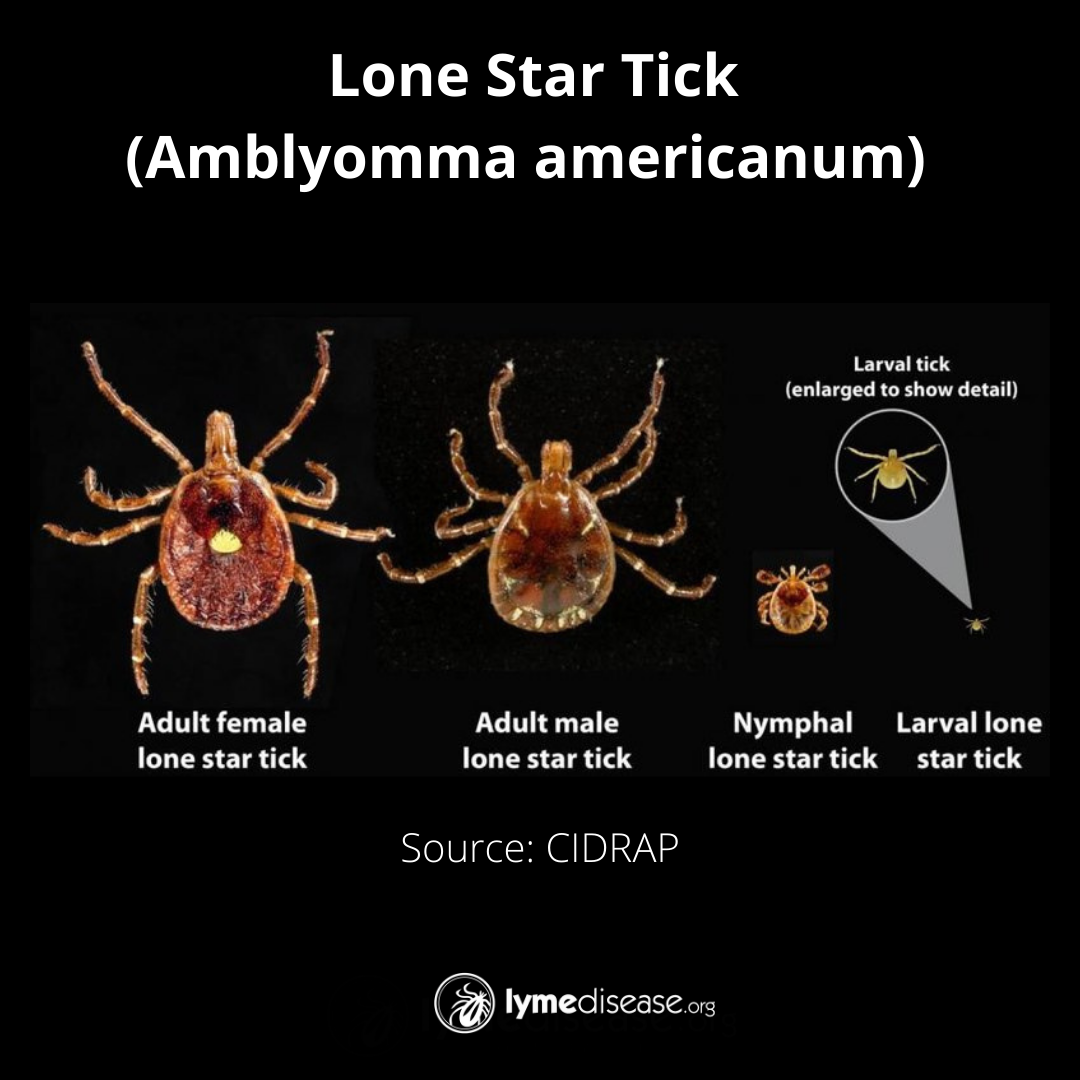

Female lone star ticks are identifiable by a single silvery-white spot on the center of their back (scutum.) The male lone star tick is slightly smaller, with varied white streaks or spots around the margins of its body.

Finding Heartland virus in Georgia

Another recent study published in the CDC journal “Emerging Infectious Diseases” found lone star ticks infected by Heartland virus in Georgia. The article points out several major knowledge gaps and the complexity of diseases carried by the lone star tick. (Romer et al, 2022)

“Heartland is an emerging infectious disease that is not well understood,” says Emory University’s Gonzalo Vazquez-Prokopec PhD, senior author of the study.

Interestingly, the genetic analysis of the Heartland virus from Georgia shows that it is 2%-5% different from previous genetic sequences of the virus.

“These results suggest that the virus may be evolving very rapidly in different geographic locations, or that it may be circulating primarily in isolated areas and not dispersing quickly between those areas,” Vazquez-Prokopec says.

The Heartland virus wasn’t officially named until 2009. However, the CDC has since found evidence of it in wild animals in at least 13 states, including stored samples from deer dating back to 2001. (Clark et al, 2018)

Because the initial symptoms of these tick-borne viruses resemble the flu, and tests for it are not readily available, it is likely being undetected and underreported in humans.

Quick and aggressive

The lone star tick moves quickly and aggressively, says Thomas Mather, PhD, Director of the TickEncounter Resource Center and co-author of the URI study.

“It is super-fast. It can move from below your knees to the top of your head in a matter of seconds.” Mather says it is the tick most frequently found attached to humans in the South.

The greatest risk of being bitten by the adults exists in early spring through fall. Lone star ticks are found mostly in woodlands with dense undergrowth and around animal resting areas, where they will quest on tall grass and low hanging branches.

Nymphal ticks quest lower to the ground but also move fast. If you encounter a patch of larvae, you’ll find they may latch on by the hundreds. Tick Encounters recommends using sticky duct tape to remove these larvae as soon as possible.

Expanding range

The range of the lone star tick in North America has increased dramatically over the past 30 years. Large numbers have been recorded as far to the northeast as Maine, as far to the southeast as Florida, as far south as Mexico and as far west as Colorado. Recently, patchy encounters have also been noted in Canada and the West coast.

Diseases carried by lone star ticks

The following is a list of symptoms of diseases caused by the bite of the lone star tick per the CDC.

Alpha-gal Syndrome (AGS)

Reactions can include:

- Rash

- Hives

- Nausea or vomiting

- Heartburn or indigestion

- Diarrhea

- Cough, shortness of breath, or difficulty breathing

- Drop in blood pressure

- Swelling of the lips, throat, tongue, or eye lids

- Dizziness or faintness

- Severe stomach pain

Symptoms commonly appear 2-6 hours after eating meat or dairy products, or after exposure to products containing alpha-gal (for example, gelatin-coated medications). Personal products that use ingredients containing “hydrolyzed protein,” lanolin, glycerin, collagen, or tallow are particularly problematic.

AGS reactions can differ from person to person and range from mild to severe. Anaphylaxis (a potentially life-threatening allergic reaction involving multiple organ systems) may need urgent medical care.

People may not react after every alpha-gal exposure.

Seek immediate emergency care if you are having a severe allergic reaction.

Bourbon Virus

Scientists are still learning about possible symptoms caused by this virus.

People diagnosed with Bourbon virus disease had symptoms including:

- fever

- tiredness

- rash

- headache

- other body aches

- nausea, and

Patients with Bourbon virus will have low blood counts for cells that fight infection and help prevent bleeding.

There is no medicine to treat Bourbon virus disease. Doctors can only treat the symptoms. For example, some patients may need to be hospitalized and given intravenous fluids and treatment for pain and fever. Antibiotics don’t work against viruses.

Ehrlichiosis

Signs and symptoms of ehrlichiosis typically begin 1-2 weeks after the bite of an infected tick. Left untreated, ehrlichiosis can be fatal. Early treatment with doxycycline is highly effective.

Early signs and symptoms (the first 5 days of illness) are usually mild or moderate and may include:

- Fever, chills

- Severe headache

- Muscle aches

- Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, loss of appetite

- Confusion

- Rash (more common in children)

About a third of people with ehrlichiosis report a rash, which can look like red splotches or pinpoint dots. This typically develops five days after the fever begins.

Early treatment can reduce your risk of developing severe illness, which can include:

- Damage to the brain or nervous system (e.g. inflammation of the brain and surrounding tissue (called meningoencephalitis))

- Respiratory failure

- Uncontrolled bleeding

- Organ failure

- Death

Heartland Virus

- Most people infected with Heartland virus experience fever, fatigue, decreased appetite, headache, nausea, diarrhea, and muscle or joint pain. Many require hospitalization.

- Some people also have lower than normal counts of white blood cells (cells that help fight infections) and lower than normal counts of platelets (which help clot blood). Sometimes, liver enzymes are elevated.

- It can take up to two weeks for symptoms to appear after an infected tick bite.

Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever

Early signs and symptoms are not specific to RMSF. However, the disease can rapidly progress to a life-threatening illness.

Signs and symptoms can include:

- Fever

- Headache

- Rash

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Stomach pain

- Muscle pain

- Lack of appetite

While almost all patients with RMSF will develop a rash, it often does not appear early in illness, which can make RMSF difficult to diagnose. RMSF rash usually develops 2-4 days after fever begins. The appearance of the rash can vary widely. Some rashes look like red splotches and some look like pinpoint dots.

Some patients who survive severe RMSF may be left with permanent damage, including amputation of arms, legs, fingers, or toes (from damage to blood vessels in these areas); hearing loss; paralysis; or mental disability.

Southern tick-associated rash illness (STARI)

It is not known whether antibiotic treatment is necessary or beneficial for patients with STARI. Nevertheless, because STARI resembles early Lyme disease, physicians will often treat patients with oral antibiotics.

The rash of STARI is a red, expanding “bull’s-eye” lesion that develops around the site of a lone star tick bite. The rash usually appears within seven days of the tick bite and expands to a diameter of three inches or more. The rash should not be confused with much smaller areas of redness and discomfort that can occur commonly at the site of any tick bite.

Patients may also experience fatigue, headache, fever, and muscle pains. The saliva from lone star ticks can be irritating; redness and discomfort at a bite site does not necessarily indicate an infection.

Tularemia

The signs and symptoms of tularemia vary depending on how the bacteria enter the body. Illness ranges from mild to life-threatening. All forms are accompanied by fever, which can be as high as 104 °F.

“Ulceroglandular” is the most common form of tularemia and usually occurs following a tick or deer fly bite or after handing an infected animal. A skin ulcer appears at the site where the bacteria entered the body. The ulcer is accompanied by swelling lymph glands, usually in the armpit or groin.

LymeSci is written by Lonnie Marcum, a Licensed Physical Therapist and mother of a daughter with Lyme. She serves on a subcommittee of the federal Tick-Borne Disease Working Group. Follow her on Twitter: @LonnieRhea Email her at: lmarcum@lymedisease.org.

References

Childs JE, Paddock CD. (2003) The ascendancy of Amblyomma americanum as a vector of pathogens affecting humans in the United States. Annu Rev Entomol. 48:307-37. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.48.091801.112728. Epub 2002 Jun 4. PMID: 12414740.

Clarke, L. L., Ruder, M. G., Mead, D. G., & Howerth, E. W. (2018). Heartland Virus Exposure in White-Tailed Deer in the Southeastern United States, 2001-2015. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene, 99(5), 1346–1349. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.18-0555

Guzmán-Cornejo C et al (2011) The Amblyomma (Acari: Ixodida: Ixodidae) of Mexico: identification keys, distribution and hosts. Zootaxa 2998:16–38

Kopsco HL, Duhaime RJ, Mather TN. (2021) Crowdsourced Tick Image-Informed Updates to U.S. County Records of Three Medically Important Tick Species. J Med Entomol. 11:tjab082. doi: 10.1093/jme/tjab082. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 33973636.

Monzón, J. D., Atkinson, E. G., Henn, B. M., & Benach, J. L. (2016). Population and Evolutionary Genomics of Amblyomma americanum, an Expanding Arthropod Disease Vector. Genome biology and evolution, 8(5), 1351–1360. https://doi.org/10.1093/gbe/evw080

Riemersma KK, Komar N. (2015) Heartland Virus Neutralizing Antibodies in Vertebrate Wildlife, United States, 2009-2014. Emerg Infect Dis. 21(10):1830-3. doi: 10.3201/eid2110.150380. PMID: 26401988; PMCID: PMC4593439.

Romer, Y., Adcock, K., Wei, Z., Mead, D. G., Kirstein, O., Bellman, S….Vazquez-Prokopec, G. M. (2022). Isolation of Heartland Virus from Lone Star Ticks, Georgia, USA, 2019. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 28(4), 786-792. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2804.211540.

Springer YP, Eisen L, Beati L, James AM, Eisen RJ. (2014) Spatial distribution of counties in the continental United States with records of occurrence of Amblyomma americanum (Ixodida: Ixodidae). J Med Entomol. Mar;51(2):342-51. doi: 10.1603/me13115. PMID: 24724282; PMCID: PMC4623429.

Steinke J, Platts-Mills T, Commins, S. (2015) The alpha-gal story: lessons learned from connecting the dots. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 135(3): 589-96.

We invite you to comment on our Facebook page.

Visit LymeDisease.org Facebook Page