LYME SCI: Lyme spirochetes in an autopsied brain (despite treatment)

An important new study from Tulane University found Lyme bacteria in autopsied brain tissue of a woman who had been aggressively treated with antibiotics.

“These findings underscore how persistent these spirochetes can be in spite of multiple rounds of antibiotics targeting them,” says Dr. Monica Embers, of Tulane.

Dr. Embers’ team collaborated with Dr. Brian Fallon, of the Lyme and Tick-Borne Diseases Research Center at Columbia University Irving Medical Center.

In their study, published in Frontiers in Neurology, the researchers performed an in-depth autopsy on the brain tissues of an elderly woman who had been previously treated for neurological Lyme disease.

And guess what? They found intact Borrelia burgdorferi, the agent that causes Lyme disease, inside portions of the patient’s brain as well as DNA evidence in her spinal cord.

Obviously, you can’t take brain samples from a living person. Therefore, autopsy samples, such as used in this study, can demonstrate that Borrelia can remain in human tissues even after extensive treatment with antibiotics. Such studies are essential in the effort to develop better diagnostics and treatment.

Persistent Lyme

Many academic researchers and physicians refer to the persistent symptoms of Lyme as post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome (PTLDS). But if you ask patients who are left disabled after being treated for Lyme, they will tell you it’s “chronic Lyme disease.”

Along with the difficulty of obtaining a proper diagnosis, the treatment for Lyme is complicated by the fact that the standard antibiotic is most effective when administered early in the disease.

Any delay in treatment allows the infection to spread throughout the body leading to a more severe chronic form of the disease. This chronic form of infection often necessitates stronger intravenous antibiotics, or longer-term antibiotics to clear infection. Even then, many patients remain ill.

Researchers from Tulane and Columbia universities want to develop better methods to detect and treat Borrelia burgdorferi.

Dr. Embers has been studying Lyme disease since 1998, mostly using animal models. Her early work demonstrated that at four months post-infection, neither a 28-day course of doxycycline nor a 90-day course of antibiotics (30 days IV Rocephin, followed by 60 days oral doxycycline) could eradicate Lyme disease. More recently, she found spirochetes in multiple organs after a 28-day course of doxycycline.

History of the patient

The new study focuses on a 69-year-old deceased woman who contracted Lyme disease at age 54. At the onset of her illness, she had a well-documented erythema migrans rash accompanied by severe headache, joint pain and a fever of 104º. Her standard two-tier tests for Lyme disease were positive on ELISA and both IgM and IgG Western blots.

She was prescribed 10 days of doxycycline which resolved her initial symptoms. Two years later, the patient developed many chronic symptoms consistent with late-stage Lyme disease, as well as dementia.

At age 60, the patient was treated with IV ceftriaxone for eight weeks, which led to 60% improvement in cognition and interpersonal engagement. Although oral amoxicillin was continued three times daily for the next six months, her symptoms gradually returned. Further antibiotic treatment with minocycline did not help. All the while her IgG Western blot for Lyme disease remained positive.

Over time, the patient’s visual, mental and executive functions continued to deteriorate. At age 62, a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) study demonstrated a positive Western blot. Unfortunately, a comparison of serum and CSF by a diagnostic ELISA was not performed at that time so she did not meet the full diagnostic criteria for neuroborreliosis.

The authors suggest that the initial symptoms of the woman at age 54 (headache, high fever) indicate brain involvement at the time of the EM rash, consistent with a mild meningitis early in the disease process.

Fifteen years after the initial diagnosis of Lyme disease, she experienced severe movement disorders, sleep disorder, paranoia and personality changes leading to a clinical diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies. Before she died at age 69, she decided to donate her brain to Columbia University for the study of the disease.

What is dementia with Lewy bodies?

Dementia is a general term referring to an impaired ability to remember, think or make decisions that interferes with one’s ability to perform normal activities of daily living.

Symptoms can vary widely from person to person. People with dementia typically have problems with:

- Memory

- Attention

- Communication

- Reasoning, judgment, and problem solving

- Visual perception beyond typical age-related changes in vision

Lewy body dementia (LBD) is associated with abnormal deposits of a protein called alpha-synuclein in the brain. These deposits, called Lewy bodies, affect chemicals in the brain whose changes, in turn, can lead to problems with thinking, movement, behavior, and mood.

In healthy people, alpha-synuclein plays a number of important roles in neurons (nerve cells) in the brain, especially at synapses, where brain cells communicate with each other. In LBD, alpha-synuclein forms into clumps inside neurons, starting in areas of the brain that control aspects of memory and movement. This process causes neurons to work less effectively and, eventually, to die.

Neuroborreliosis

Lyme disease can affect any organ or system of the body including the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord) and peripheral nervous system (nerves outside of the CNS). When Lyme infects the nervous system, it can result in Lyme neuroborreliosis.

Lyme neuroborreliosis (LNB) can develop anywhere from a few days post infection to several months or even years later. Neuroborreliosis can be the primary and only manifestation in some patients with Lyme disease. Approximately 15% of patients with untreated Lyme disease will develop LNB.

Neurological Lyme can affect many parts of the nervous system alone or in various combinations resulting in:

- Lyme meningitis – inflammation of the membranes that cover the brain/spinal cord.

- Lyme encephalitis – inflammation inside the brain

- Lyme myelopathy – inflammation of the spinal cord

- Lyme cranial neuritis – inflammation of the cranial nerves

- Lyme neuropathy – inflammation of the peripheral nerves

- Bannwarth’s syndrome – “terrible triad” of meningitis, cranial neuritis and painful neuropathy.

Lyme encephalitis is a common manifestation in LNB patients who receive delayed or inadequate treatment for Lyme disease.

Common symptoms of LNB include facial palsy, headache, stiff neck, vertigo (dizziness), cognitive dysfunction, memory or concentration problems, mood changes, sleep disturbances, or paresthesias (numbness and tingling.)

The symptoms of LNB and dementia depend on which portions of the brain are affected as follows:

- The cerebral cortex—controls many functions, including information processing, perception, thought, and language

- The limbic cortex—plays a major role in emotions and behavior

- The hippocampus—essential to forming new memories

- The midbrain and basal ganglia—involved in movement

- The brain stem—where all10 pairs of cranial nerves originate, also important in regulating sleep and maintaining alertness

- Brain regions— important in recognizing smells (olfactory pathways), and hearing (auditory pathways)

Some signs of LNB that overlap with signs of dementia may include:

- Getting lost in a familiar neighborhood

- Using unusual words to refer to familiar objects

- Forgetting the name of a close family member or friend

- Forgetting old memories

- Not being able to complete tasks independently

How Lyme persists

Unlike typical bacteria, Borrelia has the ability to evade the immune system by propelling itself to different areas of the body, changing its outer surface proteins and shapeshifting—mechanisms that also help the bacteria resist standard antibiotics.

Prior research has pointed to persistent infection as the cause of chronic Lyme disease including research by Fallon at Columbia University, Embers at Tulane University, Lewis at Northeastern University, Baumgarth at University of California, Davis, Zhang at Johns Hopkins University, Aucott at Johns Hopkins University, Novak at Harvard Medical School and many others.

Multiple studies in both animals and humans over several decades have demonstrated both inflammation and persistence of Borrelia in the nervous system following doxycycline treatment.

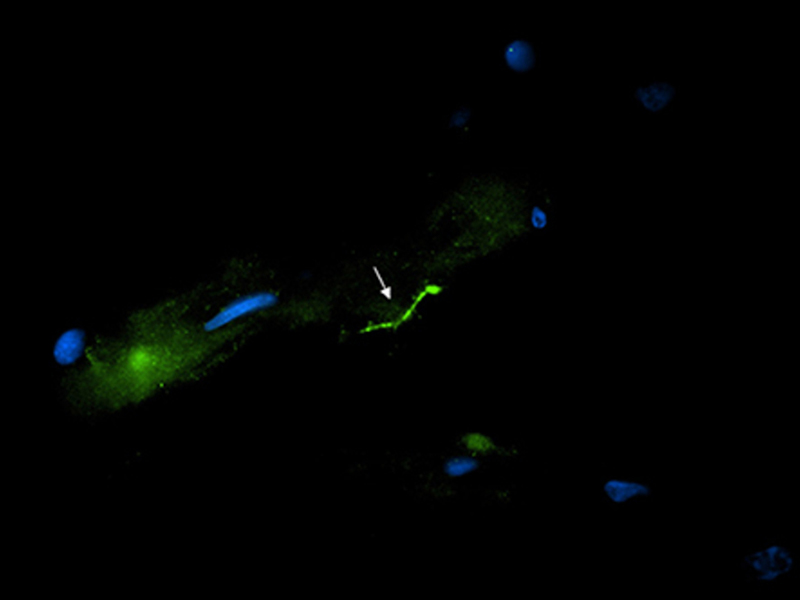

Using three highly sensitive methods of detection validated with nonhuman primate samples at Tulane National Primate Research Center, the research team concluded that at the donor’s time of death, her central nervous system still harbored intact spirochetes in spite of aggressive antibiotic therapy for Lyme disease at different times throughout her illness.

The researchers employed the use of immunofluorescence staining to image the spirochetes, polymerase chain reaction or PCR to detect the presence of B. burgdorferi DNA, and RNAscope to determine whether the spirochetes were viable.

The authors summarize the patient’s “initial good response to the IV ceftriaxone suggests a microbial infection was being treated, or that inflammation was dampened. The decline thereafter suggests either that persister Borrelia were present that are now known not to remit with standard antibiotic therapy, that an irreversible neurodegenerative process had been triggered by the prior B. burgdorferi infection, or that an unrelated neurodegenerative disorder was present at the same time as the presumed B. burgdorferi CNS infection.”

Future directions

Dr. Ember’s says the team plans to continue to investigate further tissues from other patients who have elected to donate. She hopes this study “brings more awareness to the ability of Borrelia to persist, even with extensive antibiotic therapy.”

As far as treatment, Embers believes, “we need to find something that works at all phases of the infection from acute to chronic.” She says her team is currently “collaborating with several groups to identify better treatments, be it combination therapy, targeted therapy with small molecule inhibitors, or immune boosting. All of the above!”

In light of this study, perhaps governing health agencies should reconsider the IDSA’s one-size-fits-all recommended treatment for Lyme disease. The growing body of evidence demonstrating Borrelia’s ability to survive a short course of of antibiotics, proves we need to move towards a more individualized approach to Lyme treatment.

LymeSci is written by Lonnie Marcum, a Licensed Physical Therapist and mother of a daughter with Lyme. In 2019-2020, she served on a subcommittee of the federal Tick-Borne Disease Working Group. Follow her on Twitter: @LonnieRhea Email her at: lmarcum@lymedisease.org.

References

Gadila SKG, Rosoklija G, Dwork AJ, Fallon BA and Embers ME (2021) Detecting Borrelia Spirochetes: A Case Study With Validation Among Autopsy Specimens. Front. Neurol. 12:628045. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.628045

Personal communication with Monica Embers, PhD.

We invite you to comment on our Facebook page.

Visit LymeDisease.org Facebook Page