LYMESCI: Increase of infected ticks means higher risk of tick bites

More tick bites resulting in more sick people.

That’s the result the Entomological Society of America (ESA) was trying to avoid, when in 2015, it published a “Position Statement on Tick-Borne Diseases.”

The article describes a multitude of factors that have created a near “perfect storm,” leading to more infected ticks in more places throughout the United States.

Along with other steps, the ESA recommended engaging the help of citizen-scientists. In 2016, the Bay Area Lyme Foundation (BALF) decided to do just that. The results of this groundbreaking nationwide project have recently been published—and the news is NOT GOOD!

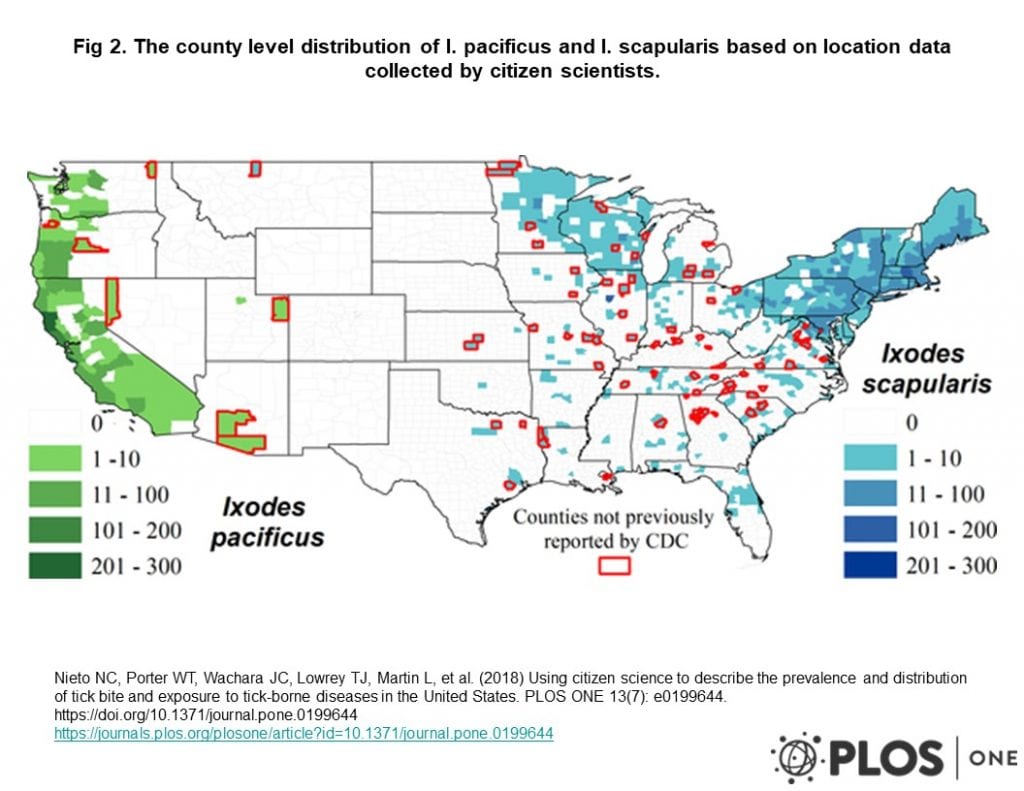

Among many disturbing facts, the new study found blacklegged ticks —carriers of 7 of 18 US tick-borne diseases—in 83 counties where they had never previously been recorded.

More tick bites = more sick people

Ticks have undergone a population explosion over the past two decades, with Ixodes ticks, the primary source of Lyme disease, now found in nearly 50% more U.S. counties than in 1996.

“Since the late 1990s, the number of counties in the northeastern United States that are considered high-risk for Lyme disease has increased by more than 320%,” says Rebecca Eisen from the Division of Vector-Borne Diseases at the CDC. “The tick is now established in areas where it was absent 20 years ago,” she adds.

The reasons for the explosion of tick populations involves complex human and environmental factors and varies by geographic region. Experts feel the major contributing factors are:

- Warming winter temperatures

- Migratory bird patterns

- Changes in landscape, land use and fragmented forests

- Abundance of vertebrate hosts (mice, deer, squirrels, etc)

- Reduction in natural predators (foxes, bobcats, etc.)

- Invasive and non-native plant species

- Accidental transport by humans (pets, livestock)

With the increase in ticks, we’ve seen a sharp rise in tick bites and tick-borne diseases, with reports of Lyme disease now coming from all 50 states, costing upwards of $75 billion per year.

What’s being done?

While the CDC lists Lyme disease as a nationally notifiable disease, the responsibility for reporting falls to each state’s health departments. The fact is, many states do not (or can’t) enforce these reporting requirements.

In addition to Lyme disease, the CDC lists six other tick-borne diseases as reportable—anaplasmosis, babesiosis, ehrlichiosis, spotted fever rickettsiosis (including Rocky Mountain spotted fever), and tularemia. Again, many states don’t put resources in tracking these illnesses.

The lack of accurate disease reporting leads to a reduction in public health awareness and medical education in areas where it’s needed. This then hinders a patient’s access to timely and accurate diagnosis and early treatment—which are absolutely critical to a good prognosis.

Citizen scientists collect ticks

BALF’s recently published tick study invited citizens from all over the US to send ticks to Northern Arizona University (NAU) for free testing, with the goal of mapping ticks and the diseases they carry.

Many Lyme advocacy groups helped spread the word. For instance, there were more than 16,000 website hits on LymeDisease.org’s announcement about the project.

Researchers had expected that maybe 2,400 ticks would be sent in. To their astonishment, they received over 16,000 ticks collected from 49 states and Puerto Rico. No ticks were received from Alaska.

As lead author Nate Nieto, PhD, associate professor in NAU’s Department of Biological Sciences, explains, “This study offers a unique and valuable perspective because it looks at risk to humans that goes beyond the physician-reported infection rates and involves ticks that were found on or near people.”

This represents the first nationwide tick study with the goal of mapping the prevalence of disease-carrying ticks throughout the United States. During the period from January 2016 through August 2017, people could send ticks to NAU, free of charge, for testing of the most common tick-borne infections:

- Borrelia burgdorferi, the cause of Lyme disease,

- Borrelia miyamotoi, which causes tick-borne relapsing fever (TBRF), a Lyme-like illness,

- Anaplasma phagocytophilum, the cause of granulocytic anaplasmosis, and

- Babesia microti, the protozoan parasite that causes Babesiosis.

The Findings

- Over 70% of submissions were the result of human tick bites.

- Blacklegged ticks were found in 83 counties (in 24 states) where they had not previously been recorded.

- All four pathogens tested for (Anaplasma, Babesia, Borrelia burgdorferi and Borrelia miyamotoi) were found in all three of the most commonly encountered hard-ticks species collected (deer tick, American dog tick, lone star tick).

- Some ticks tested positive for up to three pathogens (no ticks contained all four).

- All life stages of these three hard-tick species, including some larvae, were found to be infected with both Borrelia burgdorferi and Borrelia miyamotoi.

- On the East Coast, B. burgdorferi, the cause of Lyme disease, was predominantly detected in adult Ixodes scapularis (deer tick).

- On the West Coast, B. burgdorferi was highest in larval Ixodes pacificus (western blacklegged tick).

- The highest prevalence of Borrelia miyamotoi (a relapsing fever species Borrelia that causes Lyme-like illness) was found in larval ticks in the western US.

- Babesia was found in lone star ticks in 26 counties (in 10 states) where public health departments do not require reporting.

- Several Amblyomma americanum, commonly known as the lone star tick and capable of carrying bacteria that cause disease in humans, were found in Northern California, the first known report of this tick in the state.

Limits of the Study

While the study was hugely successful, it did have some limits. For one, the sample of ticks was limited to only those areas where citizens were participating, therefore the maps may not show all areas with ticks.

In addition, the researchers only tested for four of the many pathogens known to cause illness in humans.

Pathogens not tested for include: Multiple species of Borrelia including Mayonii, and Bisettii, which also cause Lyme-like illness; Ehrlichia chaffeensis, the cause of human monocytic erhlichiosis; Francisella tularensis, the cause of tularemia; Rickettsia rickettsii, the bacterial agent of Rocky Mountain spotted fever; multiple species of the protozoan pathogen Babesia, including duncani and divergens; and several viruses known to be transmitted by ticks including Bourbon virus, Colorado tick fever virus, Heartland virus, and Powassan virus.

Lack of funding for more studies

Lack of funding poses the biggest challenge to fully understanding the risks that ticks pose to the US population.

When asked, the CDC’s Ben Beard stated “We’ve got national maps, but we don’t have detailed local information about where the worst areas for ticks are located.…The reason for that is there has never been public funding to support systematic tick surveillance efforts.”

It’s no secret that within weeks of the first Zika infection in 2016, Congress authorized $1.7 billion in funding, of which $397 million was made immediately available to rapidly develop an accurate test and begin work on a vaccine.

That same year, the federal budget allotted only $28 million for Lyme disease—the most common vector-borne disease in the US. (Note: while the CDC can study and report on diseases, it is not allowed to lobby Congress for funding.)

What did we learn?

The big take-away from the NAU study is that ticks are everywhere, and they are full of dangerous pathogens—not just Lyme disease. This study demonstrates that ticks are spreading in range, and they are carrying more pathogens than ever before.

Until we find better ways for the CDC to report illnesses, these type of risk maps, that are generated from the pathogens the ticks are carrying, will be the best predictor of disease.

Finally, we all need to get out there and tell our representatives the dangers that lurk in our backyards. Call them. Ask to meet with them. Bring them a copy of this report. Let them know we need an dramatic increase in funding for Lyme and tick-borne diseases.

Click here for more information about ticks.

LymeSci is written by Lonnie Marcum, a Licensed Physical Therapist and mother of a daughter with Lyme. Follow her on Twitter: @LonnieRhea Email her at: lmarcum@lymedisease.org .

References:

We invite you to comment on our Facebook page.

Visit LymeDisease.org Facebook Page