LYME SCI: 12 ways you can help yourself manage chronic pain

Chronic pain–defined as ongoing pain that continues for longer than six months–is a common complaint of patients with persistent Lyme disease.

The CDC estimates that 20% of Americans currently live with chronic pain. Estimates range from 10% to 36% of Lyme patients who are diagnosed and treated early are left with chronic symptoms.

For the past 40 years, the medical definition of chronic pain was more narrowly defined, including only those patients with actual or potential tissue damage.

Recently, with the help of researchers at Johns Hopkins Medicine, the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) has made a subtle but important change to the medical definition of pain.

The new definition, “An unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with, actual or potential tissue damages,” is important as it includes the pain caused by an overstimulated nervous system, commonly associated with chronic pain.

This new more inclusive definition, if adopted by insurance providers, could have a positive impact on access to health care for disempowered and neglected populations.

Defining chronic pain

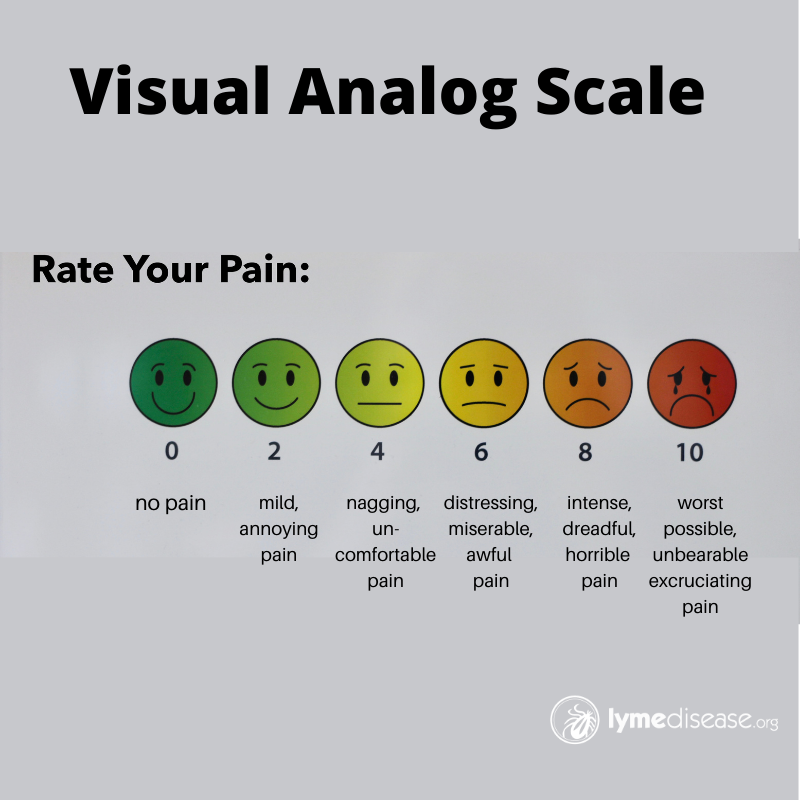

If you suffer from chronic pain, you have likely been asked to rate your pain on a scale of 1-10. As much as you may dislike rating your pain, this information helps your medical provider gauge whether you are making progress with the current treatment plan, or not.

Having worked as a physical therapist for years, I found the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) works better than telling someone to simply “rate your pain on a scale of 0-10,” especially with children.

Because Lyme disease can affect every organ and system of the body, every patient may have a different set of complaints. While neck, joint and muscle pain are very common in early Lyme disease, there are many other types of pain when the disease becomes chronic.

For instance, allodynia is a type of pain that is caused by something that shouldn’t normally cause pain (eg. wind or light touch may feel like rubbing sandpaper on a sunburn.) Menstrual pain, bladder pain, testicular pain, bone pain, and widespread nerve pain are common in chronic Lyme patients.

The “cup theory”

When I explain pain to patients, I use the cup theory. Depending on your age, your brain, and your body, everyone has a different size cup—or a different capacity—for pain. We are each only capable of handling a certain amount of pain. Once your cup is full, you are essentially at a 10 out of 10 on your individual pain scale.

You may have a constant headache filling your cup 1/2 way (or 5:10 on your pain scale), and then your knee starts hurting pushing you up to a 7:10, and then your lower back spasms, and BOOM–your cup is full!

What I’ve found is that if we can help chronic pain patients empty their cup just a little, we can start to make progress. When my daughter was at her worst, I couldn’t get rid of her pain completely. However, if I could help lower her pain even a little bit, she was able to function. Here is some of what I learned along the way.

Self-treatment

For six years, my daughter lived with chronic debilitating pain. Early symptoms included fever, neck stiffness and a migraine that would not subside. Two months later, she developed knee pain and swelling along with back and bone pain. Later, she said soles of her feet felt like she was walking on nails. Periodically, she suffered excruciating abdominal pain and nausea. And the list goes on…

The first year, she was too sick to leave the house, except for doctor and hospital visits. Luckily, as a Physical Therapist (PT), I could provide pain management treatment and modalities at home. Once she began to gain strength, after starting treatment for her infections, she started seeing an outpatient PT, who brought a whole new set of skills to the table. This also relieved me of my dual role as caretaker and healthcare provider—something I don’t recommend.

In the beginning, she was so weak I had to do everything for her. I would wheel her to the bathroom, bring her all her meals, help her get dressed–everything. The treatment I provided was limited to positioning for comfort, passive range of motion, gentle massage, hot/cold, taping/bracing, acupressure and craniosacral therapy. As she got stronger, she learned self-treatment techniques that she continues to use today.

Self-treatment approaches are generally low-cost and low-risk. You can do them on your own schedule in the comfort of your own home. It does require a commitment to changing your daily habits, but they can offer significant improvements in reducing pain and improving your quality of life.

Here are 12 things you can discuss as treatment options with your healthcare provider.

Diet

Most of the immune system originates in the gut. Literally, everything you put into your body is part of the healing process. Or not. You want to support the immune system without feeding inflammation. Fast food, artificial/processed foods, carbs, sugar, gluten, dairy and alcohol are common inflammatory triggers.

In my mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS) series, I wrote about low histamine diets that help reduce the inflammation associated with MCAS. Another great resource is “The Lyme Diet – Nutritional Strategies for Healing from Lyme disease” by Nicola McFadzean.

Positioning

When you’re in pain, it can be difficult to find a comfortable position. When my daughter was at her worst, she found it difficult to breath when she was lying flat. We added 4-inch wooden blocks under the feet at the head of her bed, and a large wedge pillow to elevate her head. When her back was hurting, it also helped to put a pillow under her knees.

You can get really creative with pillows. For instance, body pillows or “hug” pillows work well if you are a side sleeper.

While you are sitting, you may want to try out different size pillows or towel rolls for comfort. Putting a pillow on your lap to support your arms or one behind the small of your back may help. As a rule, you want to change positions every 30-60 minutes. This helps prevent pressure sores and muscle stiffness.

Some people find it worth their while to rent a hospital-type bed, where the head and/or feet can be elevated.

Assistive devices

Wheelchairs, walkers, canes, bath/shower chairs, long-handled reachers (sometimes called grabbers) are all good examples of assistive devices. Items like tray tables, lap tables, bath caddies, tote bags or tinted reading glasses can also make life easier.

Other things designed for reducing pain may include ace bandage wraps, shoulder sling, wrist, knee or ankle braces and shoe orthotics. You may also find over-the-counter topical pain relievers or CBD oil to be helpful. There are stronger topical pain relievers available by prescription.

Pacing

When you are sick you must be very conservative with energy expenditure. Modifying or changing your activities so they do not aggravate your symptoms is extremely important. Restricting, reducing, or spacing out your activities can help reduce pain and fatigue.

The key is to know your limits and stay within them. Pacing is similar to the concept of the “Spoon Theory” where you are only given a small supply of spoons to use each day—so use them wisely. When you are sick is not the time to try to push past the pain. In our house, we found sticking to a schedule that we affectionately call “Groundhog Day” helps to keep the pace.

Active range of motion (ROM) is a simple activity that almost anyone can do, whether lying down, sitting or standing. It helps to bring blood flow to the extremities and maintain or increase flexibility. The idea is to move every joint in the body through its full range. One example is to fully spread your fingers open, then fully close your fist. I recommend starting with the neck and working your way down to shoulders, elbows, wrists, torso, hips, knees, then feet.

If you are extremely de-conditioned, getting in/out of the shower and washing your hair may count as your active range of motion for that day. However, some people may be too weak or in too much pain to move at all. For these people, someone else must assist them with moving the extremities. We call this passive range of motion. While motion is important, the main goal is to make the pain better not worse.

Gentle exercise

Activity in any form can help improve mobility which may help reduce pain. Too much (or the wrong) activity can also make things worse. Once you are able, gentle exercise programs like, walking, stretching, yoga, tai chi, Pilates, and pool therapy can be a great benefit. To begin with, I recommend adding light weights (1-3 lb household items like broom handles or cans of soup work fine) to your ROM stretches.

“Sunlight Chair Yoga” is a type of adaptive yoga you may want to look at.

Meditation and mindfulness

Yoga stresses the value of deep breathing. Deep breathing involves the diaphragm, a dome-shaped muscle that forms the floor to the lungs. Such breathing is also essential to meditation and mindfulness.

The key to diaphragmatic breathing is to focus on deep relaxation and making the exhale portion of your breath twice as long as the inhale.

Meditation and mindfulness can help reduce stress and physiological responses to stress, which in turn, can help reduce pain. I suggest starting with something like Jyothi meditation, which involves simply gazing at a candle.

Stress reduction

Creating art, journaling, gardening, reading a good book, even just sitting outdoors and listening to the sounds of nature can help distract from pain. Research has shown that music helps the brain release dopamine our “feel-good” hormone. The important thing is to find something that, gives you hope, brings you joy or something you are grateful for each day. Commit to creating your own healing practice.

Hot/cold therapy

For this I recommend getting a “moist” heating pad and ice pack from your local pharmacy and use as directed. Heat can help relax muscle tightness and improve circulation. Cold can reduce inflammation and numb an area of localized pain.

I usually recommend 10-20 min of moist heat for stiffness, and 10-15 min of cold for pain. Certain types of pain may respond better to one than the other, or you may find alternating hot/cold works best. (Note: If you have problems with blood clotting, bleeding or impaired circulation, you should check with your medical provider before using hot/cold.)

Lymphatic massage

Swollen lymph nodes—lymphadenopathy—can result from Lyme disease, certain other infections, and rarely, cancer. Lymph nodes (or lymph glands) are an integral part of our immune system, designed to filter out bacteria, viruses and other waste products. Any swollen lymph node should be evaluated by a physician.

Lymph runs from distal to proximal (eg. from fingertip to armpit), flowing into a complex drainage network throughout the neck, chest, and abdomen. The best way to receive lymph drainage is from a trained professional, but there are some techniques for self-treatment.

Licensed massage therapist Heather Wibbles demonstrates the self-drainage massage I recommend most frequently for sinus headaches. Abdominal massage also works great for gastroparesis or stomach pain. If you want a deeper dive follow the link to my daughter’s full “Magic of Lymph Drainage Massage” routine.

Epsom salt

Epsom salt is a combination of magnesium, sulfur and oxygen ions known as magnesium sulfate. Most of the benefits of Epsom salt come from the magnesium, one of the most important minerals in the human body. A magnesium deficiency will create an electrolyte imbalance and can also lead to calcium and/or potassium deficiencies. Among other things, magnesium helps your body produce melatonin and certain neurotransmitters needed for sleep.

I suggest purchasing Epsom salt from your local pharmacy or other reputable supplier to ensure the highest quality and use as directed. Add the salt to a warm bathtub or foot bath. In as little as 15 minutes, it can help relax muscles, improve circulation, loosen joint stiffness, relieve pain and promote calm.

I like to add a few drops of lavender or use a diffuser for additional aroma therapy during bath time. If you don’t have access to a bath or don’t tolerate heat, magnesium can be purchased in gel form and rubbed on your skin.

Getting enough sleep

If you’ve had or have Lyme, you are likely no stranger to insomnia. During the first year of my daughter’s illness, her symptoms would peak after midnight, making it impossible for her to fall asleep until around 6 a.m. Essentially, her days and nights were reversed.

I can tell you from experience, there are a lot of standard techniques for improving sleep hygiene that simply DO NOT work for Lyme patients. So, while you are trying to turn things around, my advice is to sleep when you are tired and nap whenever possible. Even if you can’t sleep, it’s important to lie down. You need at minimum 8 hours of rest every day. Also talk to your doctor about adding a low dose of melatonin.

Other Integrative and Restorative therapies

Modalities to help improve strength, mobility, and flexibility can help to relieve pain temporarily. Over time, improved function may help reduce the underlying cause of the pain. I am a big fan of hands-on treatment by a trained professional.

The following is a partial list of therapies you might consider.:

- Acupuncture

- Acupressure

- Aquatic therapy

- Biofeedback or neurofeedback

- Bowen therapy

- Chiropractic

- Cognitive behavior therapy

- Craniosacral therapy

- Dry needling

- Feldenkrais method

- Injections or nerve blocks

- Kinesiology taping

- Lymphatic drainage massage

- Massage therapy

- Medications (as prescribed by your physician)

- Neuromuscular electrical stimulation

- Nutritional counseling

- Occupational therapy

- Osteopathic medicine

- Physical therapy

- Pilates

- Postural training

- Psychotherapy

- Qi gong

- Reflexology

- Reiki

- Support groups

- Traction

- Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS)

- Ultrasound therapy

- Vagus nerve stimulation

Laughter is the best medicine

Last but not least I do believe the key to happiness is laughter. Laughter reduces stress hormones like cortisol and releases endorphins, the body’s natural pain reliever. My simple advice is to avoid things that cause you stress, fear or anger.

Watch comedy or movies with happy endings. Stay connected with someone you can be honest with, one who listens and can make you laugh. Above all else, never give up hope.

LymeSci is written by Lonnie Marcum, a Licensed Physical Therapist and mother of a daughter with Lyme. In 2019-2020, she served on a subcommittee of the federal Tick-Borne Disease Working Group. Follow her on Twitter: @LonnieRhea Email her at: lmarcum@lymedisease.org .

References

Dahlhamer J, Lucas J, Zelaya, C, et al. (2016) Prevalence of Chronic Pain and High-Impact Chronic Pain Among Adults — United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67:1001–1006. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6736a2

Aucott JN, Rebman AW, Crowder LA, Kortte KB. (2013) Post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome symptomatology and the impact on life functioning: is there something here? Qual Life Res. 22(1):75-84. doi: 10.1007/s11136-012-0126-6.

Raja, Srinivasa N.a,*; Carr, Daniel B.b; Cohen, Miltonc; Finnerup, Nanna B.d,e; Flor, Hertaf; Gibson, Stepheng; Keefe, Francis J.h; Mogil, Jeffrey S.i; Ringkamp, Matthiasj; Sluka, Kathleen A.k; Song, Xue-Junl; Stevens, Bonniem; Sullivan, Mark D.n; Tutelman, Perri R.o; Ushida, Takahirop; Vader, Kyleq (2020) The revised International Association for the Study of Pain definition of pain: concepts, challenges, and compromises, PAIN 16(1):1976-1982 doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001939

We invite you to comment on our Facebook page.

Visit LymeDisease.org Facebook Page