MEDICAL DETECTIVE: The complex role of Bartonella in chronic illness, part 1

This article was originally posted on Dr. Richard Horowitz’s Medical Detective Substack. It is Part 1 of a 5-part series. (Scroll to bottom of this page for links to parts 2-5.) You can find more of Dr. H’s helpful content by subscribing here.

By Dr. Richard Horowitz

Bartonella is the third “B” of the triad found in the vast majority of my chronically ill patients who suffer from chronic Lyme disease/PTLDS, along with Borrelia and Babesia.

A gram-negative intracellular bacteria, it’s controversial and misunderstood and has been throwing a monkey wrench into my treatments for decades.

I barely remember learning about it in medical school, except when they were teaching me about cat scratch fever in children that would cause small, localized rashes (papules) at the site of the scratch with swollen lymph nodes and fevers.

It would be treated with a short course of antibiotics like azithromycin. These images show classical cat scratch disease before and after treatment when the lesions are starting to crust up.

[From: Mazur-Melewska K, Mania A, Kemnitz P, Figlerowicz M, Służewski W. Cat-scratch disease: a wide spectrum of clinical pictures. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2015 Jun;32(3):216-20. doi: 10.5114/pdia.2014.44014. Epub 2015 Jun 15. PMID: 26161064; PMCID: PMC4495109.]

Immune Evasion by Bartonella

Bartonella is referred to as a “stealth bacteria” because it evades the immune system by living inside red blood cells (intraerythrocytic persistence), blood vessel walls (inflaming them, causing vasculitis), endothelial cells, fibroblasts, epithelial cells of the skin (causing the classic Bartonella rashes described below), macrophages (immune cells that play a critical role of initiating and maintaining an inflammatory response, as well as potentially resolving inflammation) and bone marrow cells.

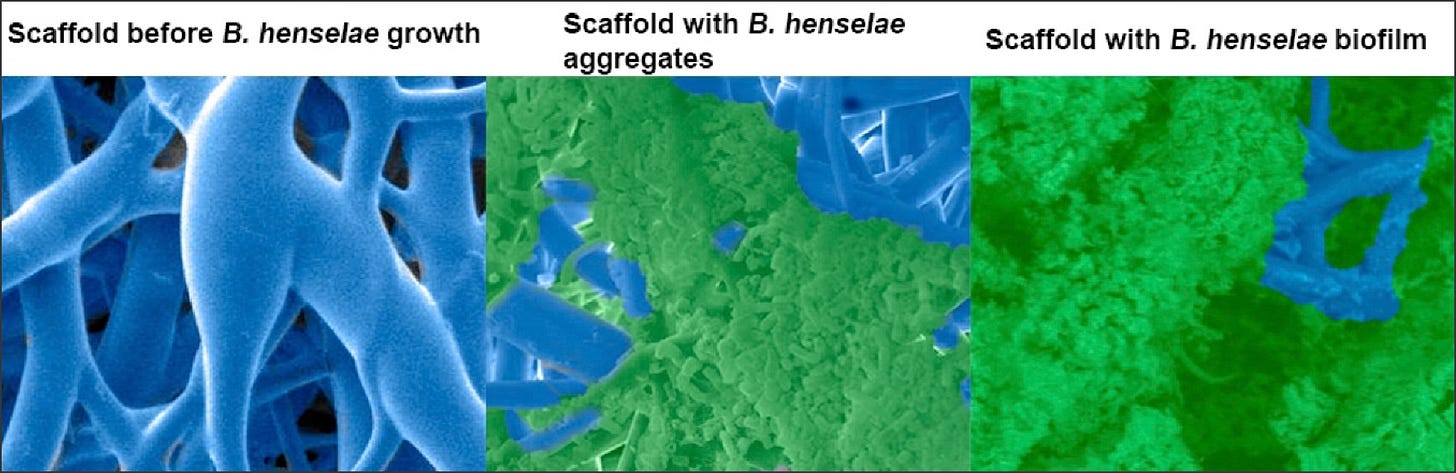

So it can hide throughout the body in areas where the immune system doesn’t easily penetrate and recognize the bacteria, not to mention, it can exist under biofilms in persister forms like Borrelia. Biofilms protect the bacteria from immune recognition and the effects of antibiotics.

[From: Okaro, U.; George, S.; Anderson, B. What Is in a Cat Scratch? Growth of Bartonella henselae in a Biofilm. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 835. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms9040835]

Bartonella can manipulate host cell interactions to hide from immune detection by altering its surface proteins to avoid recognition (like Lyme disease), and possesses unique fat and sugar molecules (lipopolysaccharides) that minimize immune response activation; this often leads to prolonged, asymptomatic infections that can be difficult to diagnose with standard tests (it can hide in the body for years in some patients without symptoms), and then reactivate under certain conditions.

The patient below was in remission for one year after doing an 8-week course of double dose dapsone combination therapy (DDDCT), and then reactivated after being treated with antibiotics for a skin infection. This skin rash emerged when he got treated for cellulitis, which had nothing to do with his initial Lyme infection. You can see the classical Bartonella “stretch marks.”

[From: Horowitz, R.I.; Fallon, J.; Freeman, P.R. Comparison of the Efficacy of Longer versus Shorter Pulsed High Dose Dapsone Combination Therapy in the Treatment of Chronic Lyme Disease/Post Treatment Lyme Disease Syndrome with Bartonellosis and Associated Coinfections. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2301. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms11092301]

Reactivation often happens when the immune system is unable to control the infection, due in part to the immunosuppressive nature of the bacteria.

I’ve found multiple species of Bartonella in our sickest patients leading to chronic variable immune deficiency (CVID), just as I’ve found Borrelia causing immune suppression, along with mold toxicity and Long Covid affecting immune functioning.

The multisystemic nature of Bartonella infections

When we see patients with Bartonella, as I mentioned, it has no resemblance whatsoever with the classical cat-scratch disease I learned about in medical school. Bacteria like Bartonella cause similar symptoms to those seen in chronic Lyme disease, presenting as a “great imitator.”

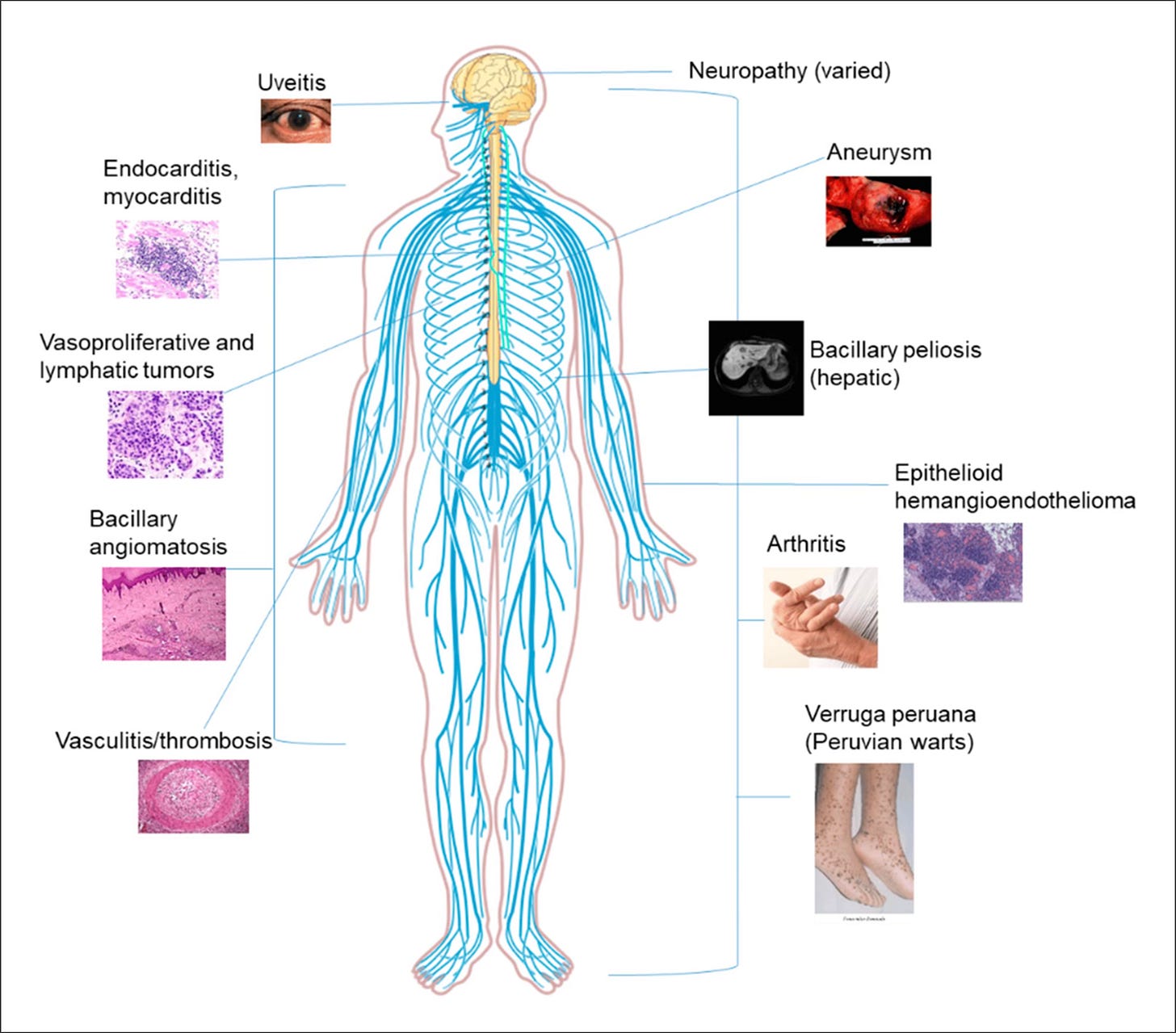

It can result in chronic fatiguing, musculoskeletal, cardiopulmonary, neuropsychiatric illness and can cause fevers, chills, fatigue, headaches, muscle/joint and nerve pain, cognitive difficulties, insomnia, depression, anxiety, and cause inflammation in every body system imaginable, just like Lyme disease, Borrelia burgdorferi, does.

There can also be inflammation in the eyes (optic neuritis, conjunctivitis, uveitis, arterial and venous occlusions); the brain, surrounding structures and spinal cord (meningitis, encephalitis, transverse myelitis, seizure disorders), with associated Bartonella “rage” and psychosis (Bartonella, like Lyme disease, can cause a broad range of psychiatric manifestations, including but not limited to severe depression, anxiety, Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, Bipolar disorder and schizophrenia with psychosis).

It also can cause inflammation in the muscles (myalgias), joints (arthritis, osteomyelitis), nerves (neuropathy) and blood vessels (vasculitis), as well as the heart valves (endocarditis, including culture negative endocarditis), heart muscle (myocarditis), and sac surrounding the heart (pericarditis) causing chest pain with masses in the chest (mediastinum) and lymph nodes resembling non-Hodgkins lymphoma.

Even the gastrointestinal tract can be affected (nausea, vomiting, weight loss, bleeding), as can the liver (hepatitis), spleen (splenitis, enlargement), and skin, which oftentimes shows signs of inflammation (stretch marks, i.e. striae; granulomas, hard fibrous areas over the knuckles, elbows, and Bacillary angiomatosis, which are tumor-like masses, raised dark areas, papules, nodules, and lesions in the skin, bones, and organs).

Bartonella is a frequently found infection in those suffering from chronic Lyme disease—I’ve seen it in up to 80-90% of all of my chronically ill patients these days and should be considered in any and all cases of FUO (fever of unknown origin).

[From: Cheslock, M.A.; Embers, M.E. Human Bartonellosis: An Underappreciated Public Health Problem? Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2019, 4, 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed4020069]

Transmission of Bartonella

Part of the reason Bartonella has been a controversial topic in the Lyme community–at least among certain physicians and researchers–is because there has only been one study to date regarding tick transmission of the bacteria, and this was in European species of deer ticks (Ixodes ricinus) with one species, called Bartonella birtlesii.

The bacteria is, however, being found in ticks throughout the world, and other studies have shown the bacteria in different ticks and in chronic Lyme disease patients.

When I was co-chair of the HHS Tick-borne Disease Working Group (TBDWG) back in 2018, I had to fight to get Bartonella included as a co-infection of importance; whether all species are able to be transmitted by ticks or not, makes no difference.

Why? To date, the number of species able to transmit Bartonella keeps increasing over the years, and most of us are exposed to these vectors on a regular basis. The most common vectors transmitting the bacteria are fleas, mites, lice, keds (not the sneakers!), spiders, red ants, ticks (probable), sand flies, black and yellow flies, and mosquitoes.

Bartonella is showing up in a broad range of vectors, so it’s possible to get exposed from many different sources. That is why the vast majority of my sick patients are testing positive for it. In fact, for most of us living on this planet, I daresay we’ll all likely be exposed to Bartonella at some point during our lives. How we handle it, and whether we get symptoms, will depend on how our immune system is functioning.

Testing for multiple Bartonella species

The table below shows some of the most common species of Bartonella seen in human disease. This is not comprehensive, as there are now at least 45 species of Bartonella, and 18 of them or more are pathogenic [capable of causing disease].

Some of the most common ones are: B. henselae (Cat scratch disease, CSD; endocarditis, neuroretinitis, lymphadenopathy), B. quintana (Trench fever, endocarditis, bacillary angiomatosis [BA]), B. clarridgeiae (bacteremia, endocarditis, CSD, chest wall abscess), B. elizabethae (endocarditis, neuroretinitis), B. bacilliformis (Carrion’s disease), B. koehlerae (endocarditis, including culture negative endocarditis), B. vinsonii subsp (bacteremia, endocarditis, fevers, neurological symptoms), B. berkhoffi (endocarditis, bacteremia, neurological symptoms), and B. grahamii (neuroretinitis).

[From: Rebekah L. Bullard, Emily L. Olsen, Mercedes A. Cheslock, Monica E. Embers, Evaluation of the available animal models for Bartonella infections, One Health, Volume 18, 2024,100665, ISSN 2352-7714, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.onehlt.2023.100665.]

How do we test for Bartonella?

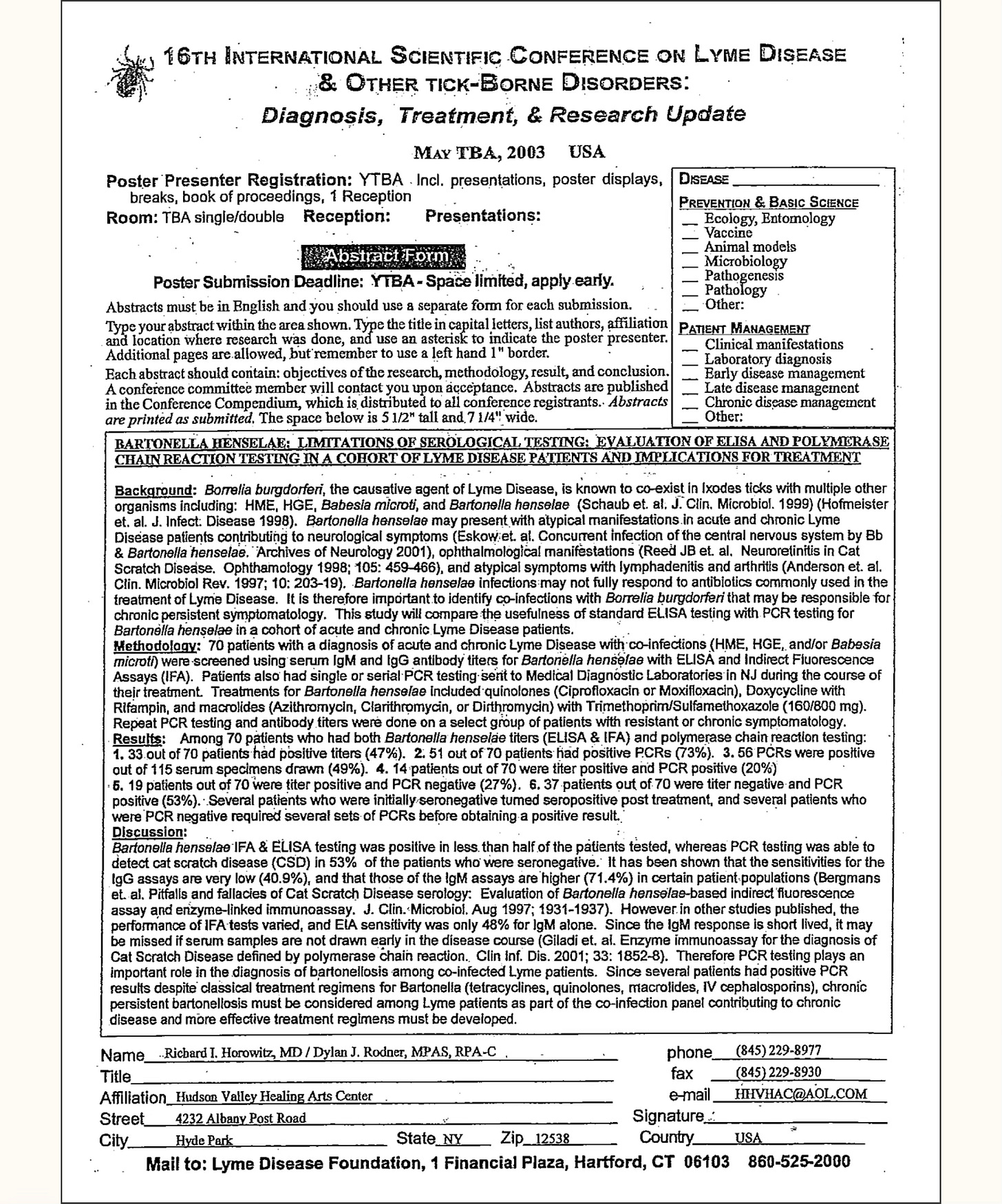

As you can see from the above table, testing for just one species makes no sense, because we can be exposed to a broad range of Bartonella species during our lifetime. I started to test for Bartonella over two decades ago. This is from an abstract I presented at the 16th International Scientific Conference on Lyme disease in 2003:

You can see from this abstract, even 22 years ago, by just testing for Bartonella henselae, one of the most common species, we found that using an ELISA and IFA (Immunofluorescent Assay) was positive in less than 50% of patients–but using DNA analysis with a PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) in the blood, we found 53% were positive when standard antibody assays were negative.

Which means the rule of thumb when testing for Bartonella is go as broad as you can. It is fine to start with local lab testing.

Level 1 testing

Using local labs like Quest, Labcorp, or Bioreference, you can send off antibody titers to B. henselae, B. quintana and B. bacilliformis, as well as PCRs and even a VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor), an indirect marker of Bartonella exposure, indicating inflammation in the blood vessels (vasculitis). Often, however, you’ll want to use several specialty labs to prove infection.

Level 2 testing

If the above testing is negative, as it usually is, but you clinically suspect Bartonella, move on to the next level of tests. The three specialty labs include IgeneX laboratory (Bartonella IgM/IgG Immunoblots, Bartonella FISH [Fluorescent In-Situ-Hybridization test, an RNA test], T Labs (Bartonella FISH) with confocal microscopy, and Galaxy Laboratories, using their 4 species IFA antibody panel (for the most common species), and their ddPCR (direct droplet PCR) tests. The Bartonella Digital ePCR™ platform combines highly sensitive ddPCR technology with culture enrichment (BAPGM™).

I usually start with IgeneX laboratory and find that most of my patients have indeterminate or positive Immunoblots. Many times a negative Bartonella FISH test will turn positive later on during treatment, after the bacteria has been flushed out from the intracellular compartments where it’s been hiding.

I follow VEGF levels over time, as an indirect marker of Bartonella, when reactivation of infection is suspected. Keep in mind VEGF can be positive for other reasons (including Long Covid or cancer with metastases).

Level 3 testing

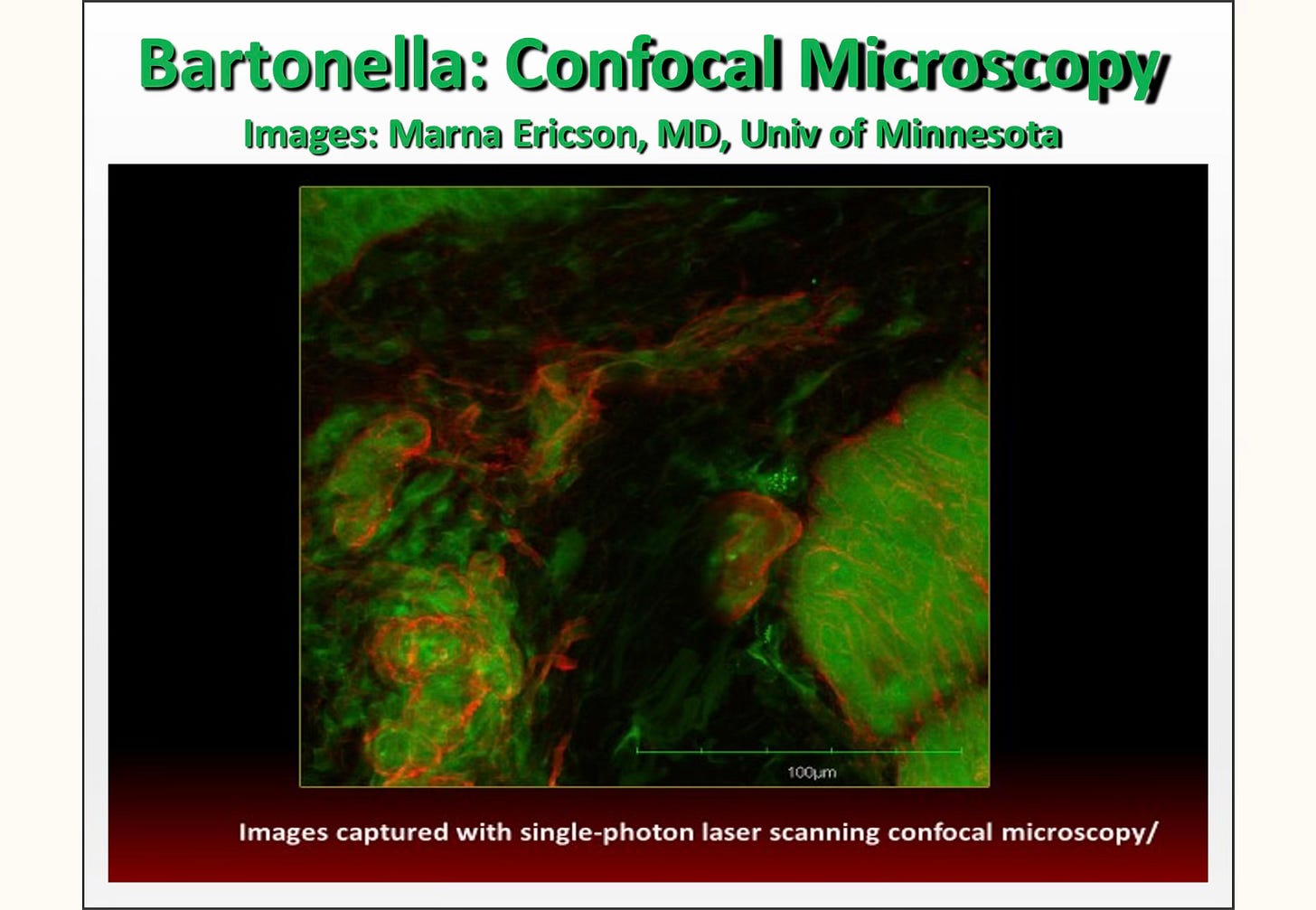

Skin biopsies can be done of the classical Bartonella rashes. Dr. Marna Ericson from T Labs has done this for me several times, and she found positive Bartonella in the skin, under biofilms, when it couldn’t be found through other methods.

I suspected Bartonella in two of my patients, but despite all classical testing, couldn’t prove exposure. The Bartonella fluoresces red under the microscope with this technique. I don’t suggest it as first level testing, but it can be very useful if you have looked for Bartonella using any and all of the above laboratories and methodologies.

See also:

Part 2: Establishing the diagnosis of Bartonella

Part 3: Effective treatments for Bartonella infections

Part 4: DDDCT protocol for treating Bartonella

Part 5: 2-week pulses of antibiotics for chronic bartonellosis

Dr. Richard Horowitz has treated 13,000 Lyme and tick-borne disease patients over the last 40 years and is the best-selling author of How Can I Get Better? and Why Can’t I Get Better? You can subscribe to read more of his work on Substack or join his Lyme-based newsletter for regular insights, tips, and advice

We invite you to comment on our Facebook page.

Visit LymeDisease.org Facebook Page