TOUCHED BY LYME: How medical education misses the (Lyme) bull’s-eye

When I first started writing this blog more than a decade ago, I remember being contacted early on by a reader with a question. She said she was a Black woman with symptoms that sounded a lot like Lyme disease.

But her doctor told her that Black people couldn’t even get Lyme disease—and then he sent her on her way. Was it true? she asked me. Was it impossible for dark-skinned people to get Lyme disease?

I remembered her question this week, while reading an article in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM). It’s called “How Medical Education is Missing the Bull’s-eye.”

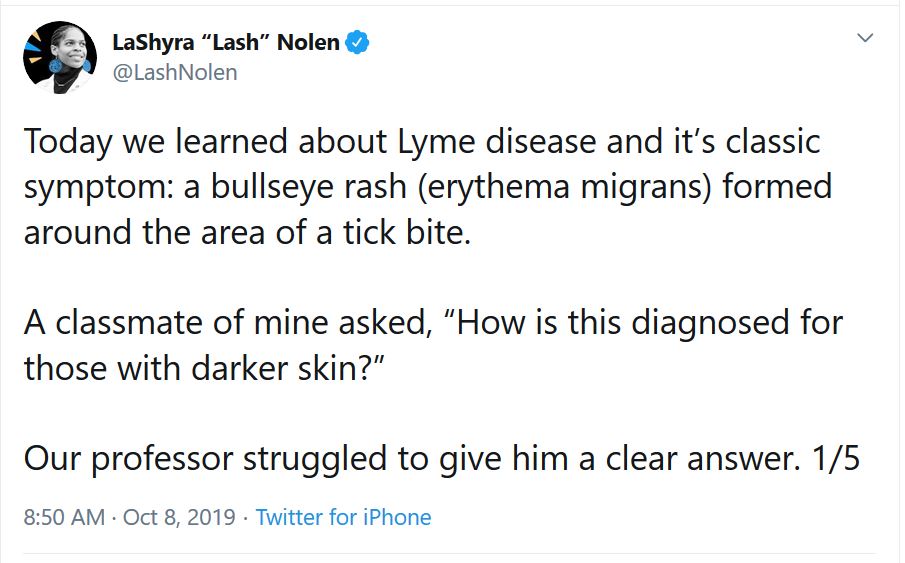

It’s written by a Black medical student from Harvard named LaShyra Nolen. It grew out of something she posted on Twitter in October 2019. Here’s the original tweet:

That remark garnered a lot of traction in cyberspace, with more than 7300 retweets and comments and more than 17,000 likes.

Her initial posting sparked a substantive dialog on Twitter (click here to read the thread) and its effect didn’t stop there.

Digging Deeper

Spurred by the interest her Twitter post had ignited, Ms. Nolen started digging deeper. Ultimately, she wrote the article published this week in NEJM, considered one of the top medical journals in the nation.

In it, she describes how her teachers and textbooks tend to focus on white men’s bodies—paying little heed to how disease affects female and minority populations.

She writes:

My mind started racing with questions: “Is the diagnosis of Lyme disease in black and brown patients delayed? Do these patients therefore present with more advanced symptoms, such as neurologic disorders and arthritis, than white patients?”

More research revealed that my hypotheses were correct. One study of patients with Lyme disease found that there was a higher proportion of diagnoses of arthritis (late-stage Lyme disease) and a lower proportion of diagnoses of erythema migrans (stage 1 Lyme disease) among Black patients than among white patients.

From the images in textbooks used in medical school to the photos displayed at medical conferences, she writes, “patients of color are grossly underrepresented in medical educational material. If medical students and trainees are taught to recognize symptoms of disease in only white patients and learn to perform lifesaving maneuvers on only male-bodied mannequins, medical educators may be unwittingly contributing to health disparities instead of mitigating them.”

The inadequate training of medical students regarding Lyme and other tick-borne diseases is a long-standing problem on many levels. Ms. Nolen’s article shines new light on that concern. I urge you to read the entire article and study the side-by-side photos of Lyme rashes on black vs. white skin.

(It must also be noted that not everybody with Lyme gets a rash, and even among those who do, it’s not always shaped like a bull’s-eye. Doesn’t sound like that possibility was even presented in the class last October.)

“Misdiagnosis by skin color” is a topic LymeDisease.org would like to explore further. If you are a person of color who has had trouble getting properly diagnosed for Lyme disease and are willing to share your story, please send me an email at dleland@lymedisease.org.

TOUCHED BY LYME is written by Dorothy Kupcha Leland, LymeDisease.org’s Vice-president and Director of Communications. She is co-author of When Your Child Has Lyme Disease: A Parent’s Survival Guide. Contact her at dleland@lymedisease.org.

We invite you to comment on our Facebook page.

Visit LymeDisease.org Facebook Page