I n 2002, my husband and I became seriously ill after a vacation to Martha’s Vineyard. It took ten doctors and a year to discover the root cause: We’d been bitten by unseen ticks harboring the parasites that cause Lyme disease and babesiosis, a malaria-like disease.

Our road to recovery was grueling, requiring five years of intermittent antimicrobial treatments. Later, I discover that my situation wasn’t all that uncommon. About one in five Lyme patients continue to suffer from ongoing symptoms after being treated with the recommended course of antibiotics. After that experience, it was abundantly clear that we need better treatments.

Our road to recovery was grueling, requiring five years of intermittent antimicrobial treatments. Later, I discover that my situation wasn’t all that uncommon. About one in five Lyme patients continue to suffer from ongoing symptoms after being treated with the recommended course of antibiotics. After that experience, it was abundantly clear that we need better treatments.

That’s why I was excited to hear about a study from Stanford Medicine researchers and their collaborators that provides evidence that the drug azlocillin eliminates the bacteria that cause Lyme disease at the onset of infection in lab mice and cultures.

Lyme disease, the most common vector-borne disease in the United States, affects more than 300,000 people a year. It is caused by the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi, which is transmitted to humans through the bite of infected blacklegged ticks. If the disease isn’t treated promptly, it can lead to life-threatening heart issues and chronic neurological problems. Common persistent Lyme symptoms include fatigue, joint pain, muscle pain, numbness, tingling, burning pains, and changes in mood, memory or mental clarity.

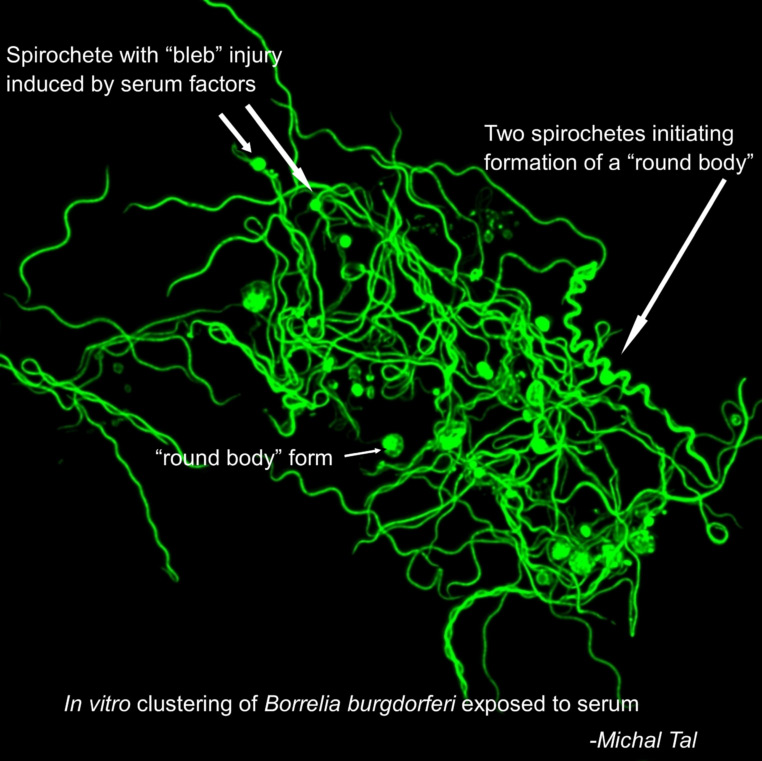

Drug-tolerant bacteria causing symptoms

Standard treatment of Lyme disease is oral antibiotics, typically doxycycline, in the early stages of the disease; but for reasons that are unclear, the antibiotics don’t work for up to 20% of people with the tick-borne illness. One possibility is that drug-tolerant bacteria cause the lingering symptoms.

This drug study, published online in Scientific Reports, was conducted by a team led by Jayakumar Rajadas, PhD, assistant professor of medicine and director of Stanford’s Biomaterials and Advanced Drug Delivery Laboratory, and research associate Venkata Raveendra Pothineni, PhD.

Azlocillin appears to kill drug-tolerant persisters very effectively. These protective persisters form when the bacteria are threatened with defensive immune system biochemicals or antibiotics.

Azlocillin is a Promising drug candidate for Lyme disease

The team zeroed in on azlocillin as a promising drug candidate through the use of high throughput drug screening. This process entails acquiring “libraries” of thousands of known chemical compounds and drugs, then mixing Lyme bacteria with each in tiny wells to see which ones are best at killing the organisms. The best drug candidates were retested in larger culture dishes, then the safest of these were tested in vivo in seven mice.

Early results of this team’s screening process, first published in 2016, led to the discovery of another promising Lyme drug candidate, disulfiram, which is approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of alcohol abuse disorder. This drug is currently being evaluated in a clinical trial with previously-treated Lyme patients. The trial coordinators are still looking for volunteers.

According to the recent study, azlocillin shows promise because it appears to be able to kill the two morphological forms of the Lyme bacteria — the actively replicating spiral forms and the semi-dormant round-body forms.

Azlocillin appears to kill drug-tolerant persisters

Azlocillin also appears to kill drug-tolerant persisters very effectively. These protective persisters form when the bacteria are threatened with defensive immune system biochemicals or antibiotics. After the threat has passed, the bacteria can reemerge to cause active disease. Many researchers believe that doxycyline’s inability to clear the persisters may account for the ongoing symptoms of some Lyme sufferers.

Although azlocillin is an FDA-approved drug, more research needs to be done before it is used to treat Lyme patients. Rajadas and Pothineni have patented the compound for the treatment of Lyme disease and are working with a company to develop an oral form of the drug. Researchers plan to conduct a clinical trial.

As Pothineni said in the Stanford Medicine news release:

“We have been screening potential drugs for six years … We’ve screened almost 8,000 chemical compounds. We have tested 50 molecules in the dish. The most effective and safest molecules were tested in animal models. Along the way, I’ve met many people suffering with this horrible, lingering disease. Our main goal is to find the best compound for treating patients and stop this disease.”

A former science writer with Stanford Medicine, Kris Newby is the author of Bitten: The Secret History of Lyme Disease and Biological Weapons. She is now working on a documentary based on the book.

Photo by Gabor Tinz/Shutterstock. Image courtesy of Michal Tal, PhD, instructor at Stanford’s Institute for Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine. Article reprinted with permission from Stanford’s Institute for Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine: https://scopeblog.stanford.edu/2020/03/30/lyme-disease-bacteria-eradicated-by-new-drug-in-early-tests/

Editor’s note: Any medical information included is based on a personal experience. For questions or concerns regarding health, please consult a doctor or medical professional.