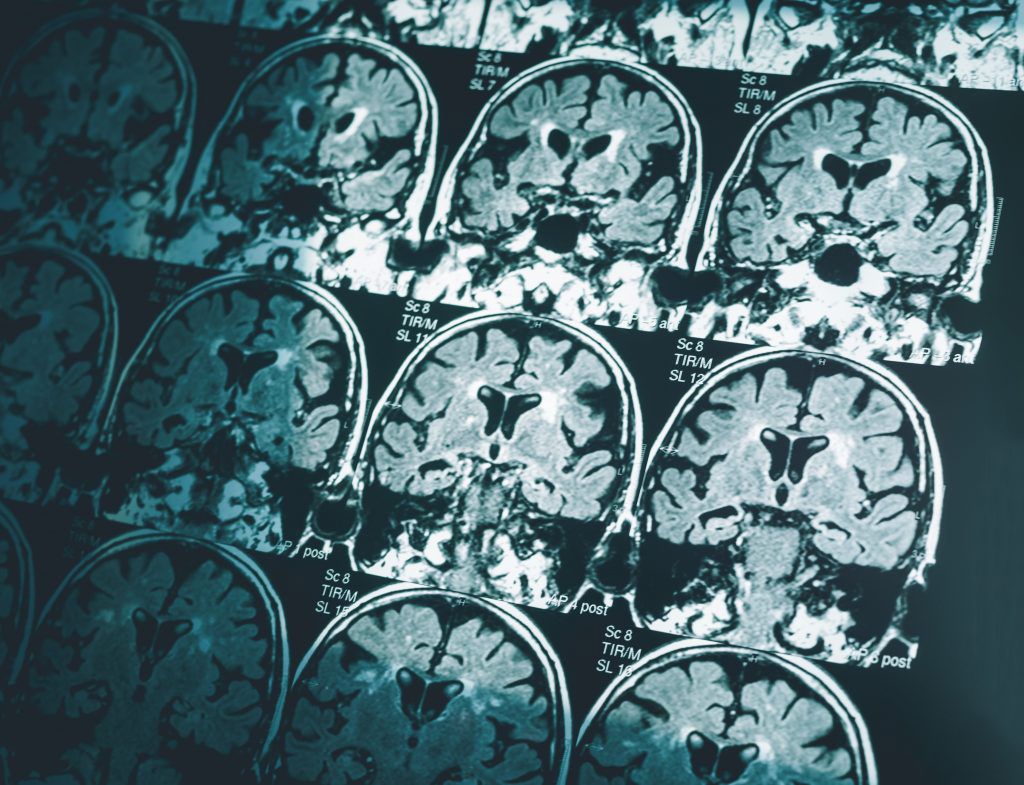

U nlike diseases that impair the body in myriad physical ways, dementia can rob patients of mental faculties and identity, as they struggle to remember memories from previous days.

As the disease progresses, patients may also forget friends or relatives and the functional skills to perform a daily routine.

The most common form of dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, is a disorder in which brain cells shrink and die. There is no cure, although some medicines, support groups, and other programs may help patients manage the disease.

The most common form of dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, is a disorder in which brain cells shrink and die. There is no cure, although some medicines, support groups, and other programs may help patients manage the disease.

Considering this void, the search for better treatments presses on. More than $3 billion in National Institutes of Health funding is dedicated to Alzheimer’s research, although progress seems painfully slow for the roughly 5.8 million Americans currently living with the disease.

Some existing drugs are controversial, such as Aduhelm, which was recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration for patients with mild cognitive impairment or early onset Alzheimer’s. Among the many questions about the drug is whether it is worth its $56,000 a year cost and side effects risk.

Revisiting an Old Drug

The glaring limitations of available therapeutics led one professor at the Drexel University College of Medicine to consider whether the solution is not an expensive drug, but one that has been around since World War II.

This is the question posited by Herbert B. Allen, MD, a professor and chair emeritus in the College of Medicine. He offers a bold challenge to colleagues: consider whether penicillin could help prevent Alzheimer’s, and when combined with a disperser, whether penicillin may slow progression of the disease — or maybe even stop it altogether.

Allen’s hypothesis paper, recently published in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, explains penicillin’s current role in treatment of infections, like syphilis and gonorrhea, and introduces the possibility that there could be similar effectiveness when applied to Alzheimer’s…….Join or login below to continue reading.