A Parent’s Survival Guide for When your Child has Lyme Disease A look at the many complex personal and family issues that arise with diagnosis.

I n 2005, out of the blue, my then-13-year-old daughter Rachel became so disabled from a mysterious pain condition that she needed to use a wheelchair. At that time, I didn’t even know what Lyme disease was.

I also didn’t know that our family had fallen into a huge medical controversy, what many have dubbed “The Lyme Wars.” And I did not anticipate the many complex personal and family issues that would arise. We felt alone. But, in fact, we were part of a growing yet invisible group—families grappling with a disease that is largely ignored by the medical establishment.

It was a long, hard, expensive slog but, eventually, our family got through it. We were guided by Internet research and online patient support groups. In time, we found our way to medical practitioners and treatments that put our daughter’s health back on track and allowed her to leave that wheelchair behind for good. At that point, I entered the world of Lyme disease activism, trying to help change a system that drastically harms so many families.

Since then, I’ve regularly encountered parents who face the same issues my family did. Many of them are in even more daunting circumstances.

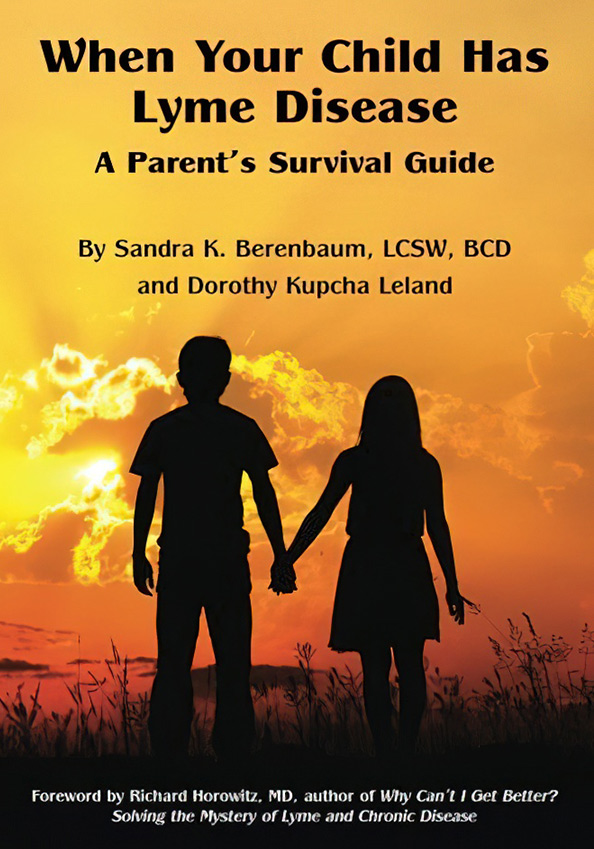

Author: Dorothy K. Leland and Sandra K. Berenbaum

Wanting to shorten the learning curve for parents and family members of children with Lyme disease, I co-authored a book with Lyme-literate family therapist Sandra Berenbaum, When Your Child has Lyme Disease: A Parent’s Survival Guide.

In the following excerpt, I discuss the frustrating process of trying to figure out what was causing

my daughter’s troubling symptoms.

As we continued on our merry-go-round of medical appointments, I noticed a disturbing pattern. Each time we saw a new practitioner, the conversation went something like this:

Nurse: “Please rate your pain on a scale of one to ten. One is hardly any pain at all and ten is the worst pain you can imagine.”

Rachel, with no hesitation: “Ten.”

Nurse (smiling and shaking her head): “Oh, no, dear. You don’t understand. It’s not a ten. You’re not in that much pain. Ten is the worst pain you can possibly imagine.”

Rachel, with no hesitation: “Ten.”

Nurse, sighing: “I’ll put down an eight.”

Then she leaves the room.

It soon became obvious that this was a pervasive mindset. The practitioners had a mental image of what ten-out-of-ten pain looked like, and Rachel didn’t match it. To them, she just looked like a normal girl sitting in a wheelchair. Because at that moment she wasn’t howling in anguish, she couldn’t possibly have excruciating pain. (One nurse said, “No dear, number ten pain would be at least equal to childbirth.” As if my 13-year-old daughter had a frame of reference for that.)

Part of the problem was how they phrased it. They always said, “Ten is the worst you can imagine.” I once pointed out that maybe this was the worst Rachel could imagine. The nurse glared at me and said, “Let her answer for herself.”

I wanted to cry out to every medical person we saw: She feels like she’s being stung by bees! We have to push her on a rolling office chair to get to the bathroom. Sometimes her foot feels like it’s on fire. But they just seemed to want a data point for their chart.

Children with Lyme disease may experience many different kinds of pain. It can be difficult to figure out what’s causing it. Many of them hurt for years, with little help or understanding from the medical system. And because children may not be adept at describing their pain, it is often underestimated.

Here’s what one mother said about a daughter whose symptoms began at age 5:

I was told that the eye pain was because she was in kindergarten and starting to read, the joint pain was growing pains, and the fatigue was just her talking and getting attention or being lazy, and she needed more exercise.

Three years later, the girl’s symptoms and pain intensified.

They mentioned psychiatric stuff and took her in a separate room to ask if this was attention-getting because maybe she had been molested (their theory). They said to wear supportive shoes. They gave her no good pain meds. They offered ibuprofen…. She was supposed to go to a special study for children with inexplicable pain (since she absolutely positively could not possibly have Lyme, because it “doesn’t exist” in California) but somehow that never happened.

When a child is suffering and the doctors aren’t helping, it’s common for a parent to doubt herself.

A New York mother recounts that her child, whom I will call Becky, began to experience leg pain when she was 2 or 3 years old.

By age 6, Becky suffered from lots of muscle and joint pain, headaches, stomach aches…She was often unable to walk due to the pain in her legs and the extreme weakness that would hit. I got her crutches, which helped some when she needed them. At times she would be walking along the room and then just melt into the floor and scoot on her bottom to get to where she was going.

As the pain continued for years, her mother reports, Becky hated being asked to rate it on the one to ten scale. “She never really knew a life without pain. So it was difficult to rate something as none-to-horrible when all you knew was moderate-to-horrible.” Finally, at age 14, Becky was diagnosed and treated for Lyme disease and her pain reduced significantly.

Lyme disease is named after Lyme, Connecticut, where it was first recognized in the 1970s. The area continues to be a hotbed for the infection. So, it shouldn’t be a stretch for a doctor in that state to suspect Lyme disease in a sick child, especially when there’s a known tick bite. Yet, that is not the experience of many families.

A Connecticut mother tells of her 3-year-old boy, who had been bitten by a tick. Soon, he experienced knee pain, rashes, and fevers that would come and go. “Because we had gotten the tick out right away and it wasn’t engorged, we were told it couldn’t possibly be Lyme disease.”

The knee pain worsened. He no longer wanted to run and play, but rather sat listlessly all day. The mother pushed to have him evaluated for Lyme disease, but the doctors dismissed her concerns. When their son was still in pain nine months after the tick bite, the family finally took him to a physician more familiar with Lyme disease. This doctor found that the child indeed had Lyme. Antibiotic therapy has relieved many of the symptoms, though at this writing, treatment is on-going.

Lyme-related catastrophic illness is like a house on fire. Families need help battling the flames and rescuing their children.

At this stage of the game, when a child is suffering and the doctors aren’t helping, it’s common for a parent to doubt herself. Am I doing everything I can to help my child? Is there something I’ve overlooked? God forbid, is this somehow my fault? Unfortunately, the medical establishment often creates or feeds these doubts.

The mother is usually the one who is most engaged with the afflicted child. She shares those sleepless nights, witnesses firsthand the child’s anguish, and shuffles the youngster to medical appointments. Yet, her ideas about what might be going on are often dismissed by the so-called experts. They may say she is “overly engaged” with her child’s health problems. Or, like in my case, that I somehow “wanted” my daughter in a wheelchair.

At one point, before we knew what was wrong with Rachel, I made an appointment to see a counselor myself. The stress of her deteriorating condition was taking a toll on me, too, and I needed help holding things together. The therapist told me flat out that I spent too much time thinking about my daughter’s health. She said I needed to develop other interests. At the time, I was too flummoxed to reply.

But here’s my response: “What if my child was trapped inside a house that was on fire, and I was trying to get her out? Would you say I was ‘overly engaged’ with her welfare? Would you say I should stop trying to save her and find myself a hobby?” Lyme-related catastrophic illness is like a house on fire. Families need help battling the flames and rescuing their children.

Editor’s note: Any medical information included is based on a personal experience. For questions or concerns regarding health, please consult a doctor or medical professional.