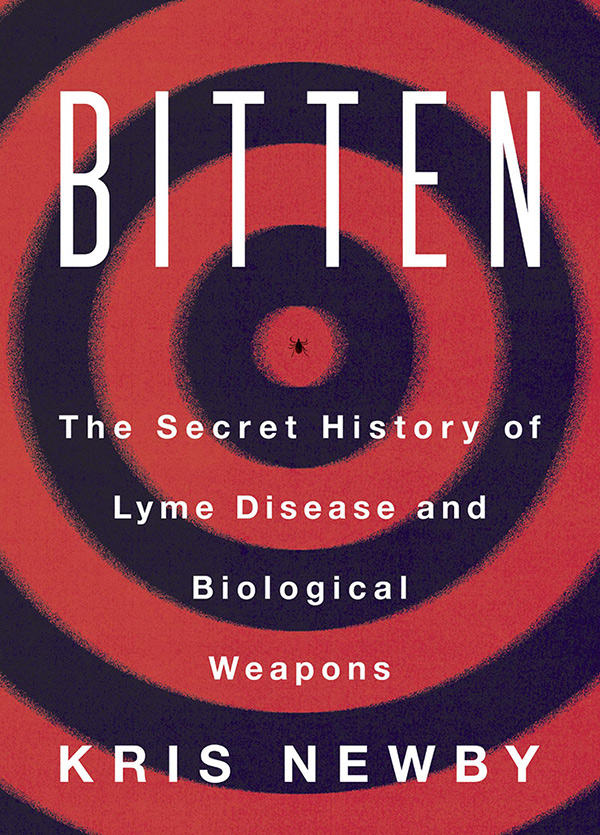

Is Lyme Disease a Bioweapons Experiment Gone Bad? Kris Newby’s book, Bitten: The Secret History of Lyme Disease and Biological Weapons, is a wakeup call.

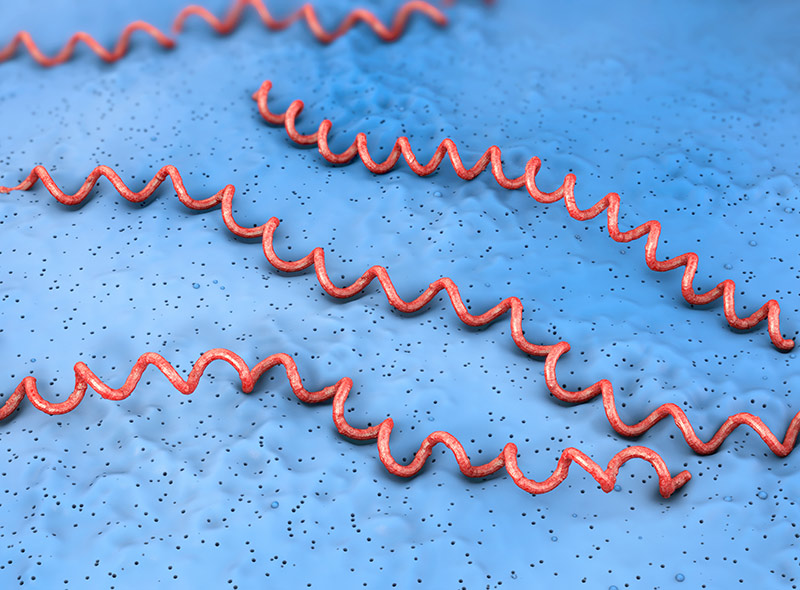

T he mainstream “origin story” of Lyme disease in the United States goes like this: In the 1970s, a mysterious ailment afflicted a group of people in and around Lyme, Connecticut. Eventually, scientists determined it was caused by a spirochete transmitted by the bite of an Ixodes tick. A short course of antibiotics would resolve the issue. Mystery solved. Problem fixed.

Since then, that’s basically the script followed by health officials, researchers who receive government funding to study Lyme disease, and the medical establishment.

Unfortunately, says science journalist Kris Newby, “the chasm between what researchers say about Lyme disease and what the chronically ill patients say they are experiencing has remained an open wound for decades.”

And Newby knows what she’s talking about.

In 2002, while vacationing on Martha’s Vineyard in Massachusetts, she and her husband Paul were bitten by unseen ticks.

“These tick bites would rob us of our good health,” Newby writes, “and send me on an investigation into an almost unimaginable possibility: that we were collateral damage in a biological weapons race that had started during the Cold War.”

Upon their return to California, Newby and her husband got horribly sick. A succession of medical experts couldn’t pinpoint the problem and eventually dismissed them as patients. This happened despite the fact that Newby had a positive Lyme test, which her doctors rejected as a false positive.

For readers not familiar with the issue, here it is in a nutshell: Hundreds of thousands of people get sick every year in the U.S. with Lyme and other tick-borne illnesses. But for complex reasons, patients have a devil of a time getting properly diagnosed and treated.

Newby’s case was typical. She saw 10 doctors before stepping out of the medical mainstream and paying out of pocket for a physician who could recognize what she had and knew how to treat it. A point of contention in the controversy is whether the illness can persist after the patient receives a short course of antibiotics.

Government/medical establishment folks say no. But patient experience says yes.

In time, Newby found her way to a physician who was familiar with tick-borne illnesses. This doctor diagnosed her with Lyme disease and babesiosis, both prevalent in ticks on Martha’s Vineyard. Then, she began years of treatment that slowly brought her back to health.

Under Our Skin

During her recovery, Newby started working with film director Andy Abrahams Wilson, of Open Eye Pictures. They jointly researched what became the award-winning Lyme documentary Under Our Skin, which delves into the history of the Lyme disease controversy.

During her recovery, Newby started working with film director Andy Abrahams Wilson, of Open Eye Pictures. They jointly researched what became the award-winning Lyme documentary Under Our Skin, which delves into the history of the Lyme disease controversy.

In the course of filming Under Our Skin, Newby and Wilson struggled to find a government expert on Lyme disease willing to be interviewed on camera. The CDC, the NIH, and others declined.

“The politics of the disease were too charged,” she writes, “and the government researchers seemed to want to steer clear of the controversy.”

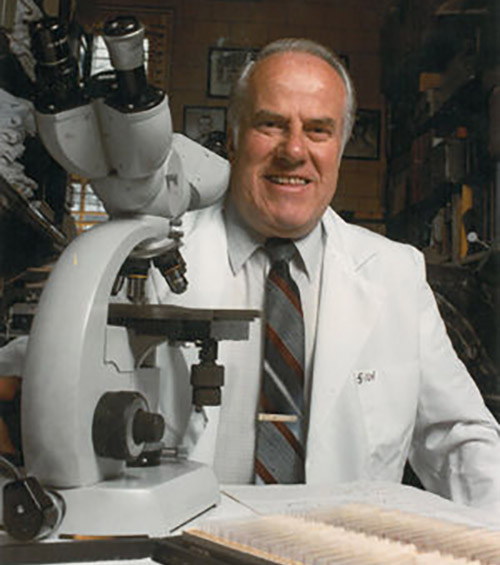

Then they met retired NIH researcher Willy Burgdorfer, the discoverer of the Lyme spirochete—Borrelia burgdorferi—for whom it is named. In contrast to others they had sought out, Burgdorfer seemed eager to talk.

“Willy told us that the U.S. government knows that Lyme disease can become chronic and that patients can relapse years after an initial infection,” Newby writes, “and that the disease is particularly damaging to the neurological systems of children.”

Lyme Disease Research – A Shameful Affair

Furthermore, Burgdorfer criticized the dozen or so researchers who have received most of the government funding for Lyme disease.

“The controversy in Lyme disease research is a shameful affair,” he said on camera.

He stated that the work should instead be done by scientists “who don’t know beforehand the results of their research.”

Then, Newby writes, “as soon as we turned off the camera and began packing up our gear, Willy told us with a smile, ‘I didn’t tell you everything.’ But try as we might, we couldn’t get him to say more.”

Under Our Skin was released in 2008. Now, fast-forward to the present day. Newby’s new book, Bitten: The Secret History of Lyme Disease and Biological Weapons, describes her years-long effort to understand who Burgdorfer was and to get to the bottom of what he hinted at that day.

Turning Ticks Into Lethal Weapons

Burgdorfer grew up in Basel, Switzerland, and became fascinated with ticks while a PhD student at the Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute. At the end of his training, in 1951, he took a position at the U.S. government’s Rocky Mountain Laboratories in Montana. It held the most extensive collection of ticks in the country.

At first, it appeared that the job involved figuring out how to protect people and animals from tick-borne diseases. However, Burgdorfer was apparently soon disabused of that notion. During that Cold War era, the U.S. government was heavily involved in bioweapons research. Scientists sought ways to turn infectious microbes—such as anthrax, the plague, brucella, and tularemia—into potent military tools that could disable a huge population. (Perhaps the Russians?)

Newby writes about a particular meeting Burgdorfer attended in Canada: “After hearing from a roomful of entomological warfare experts … he now most certainly knew that he was no longer protecting humans from tiny eight-legged beasts. He was instead turning those beasts into lethal weapons.”

The author does a stellar job of sifting through a huge collection of clues. But some answers remain tantalizingly out of reach. “If the outbreak was caused by a U.S. accident, we need it exposed,” she writes. “If it was a hostile act by a foreign actor, then it shows how woefully unprepared we are for future attacks.”

Burgdorfer spent time at Fort Detrick, Maryland, where one of the buildings was nicknamed the “Anthrax Hotel.” Another structure housed the “Eight Ball,” a massive cloud chamber used for testing airborne bioweapons on animals and human volunteers.

He brainstormed with entomologist James Oliver, who was working on a program to drop weaponized ticks out of airplanes. He traveled to England and Czechoslovakia to meet with scientists doing similar work.

Burgdorfer also experimented with ways to infect ticks with more than one pathogen at a time.

Documentation Of Tick-borne Bioweapons Research

Newby meticulously documents all of this with massive archival research, discussions with many people knowledgeable about bioweapons research in the U.S., and another interview with Burgdorfer himself in 2013.

By then, advanced Parkinson’s disease was stealing Burgdorfer’s ability to speak clearly, and his health was failing. (In fact, he would die the following year.)

At this point in the book, the reader is itching to know: Will he give specifics? Was the outbreak of sickness in and around Lyme, Connecticut, in the 1970s connected to bioweapons research? Was there an accidental release of pathogens? Or a deliberate one?

Newby writes, “It was frustrating that he still wouldn’t disclose key details on the who, what, and where of the alleged bioweapons accident. He offered me more pieces of the puzzle, but for unknown reasons, he was holding back on the whole story.”

In this final interview, Burgdorfer confirmed that he had been working on tick-borne bioweapons research—and insinuated there had been an accidental release of some sort.

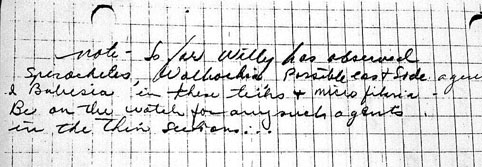

Even more puzzle pieces would emerge in the months before his death. It turns out Burgdorfer had a trove of Lyme-related research notes that he had never relinquished to government archivists. He instead wanted them preserved for posterity in a university library. (They are now available online at Utah Valley University.) More complexities would surface after Burgdorfer’s death, when his widow provided additional materials for the academic archive.

The Swiss Agent

Newby went through these records with a fine-tooth comb. Most intriguing were Burgdorfer’s references to something he dubbed the Swiss agent. Was this another pathogen? Could it be what makes Lyme disease so virulent? Why was it never mentioned in any of Burgdorfer’s journal articles? Why wouldn’t he talk about it?

The author does a stellar job of sifting through a huge collection of clues. But some answers remain tantalizingly out of reach. “If the outbreak was caused by a U.S. accident, we need it exposed,” she writes. “If it was a hostile act by a foreign actor, then it shows how woefully unprepared we are for future attacks.”

The Lyme community cares passionately about the true origin story of this burgeoning epidemic. Indeed, the microbe has been around for eons. Lyme spirochetes have been found in ticks that were encased in amber 15 million years ago. Lyme DNA is in the bones of “The Iceman,” who lay frozen in the Alps for over 5000 years. But did something happen in the last half of the 20th century to ramp up this pathogen’s virulence? And/or that makes it spread more easily? Newby’s book certainly suggests that.

Burgdorfer died in 2014, leaving behind significant “dots” without connecting them all. The aforementioned James Oliver died in 2018, two years after giving a magazine interview about his bioweapons research at Fort Detrick. (He said one of his goals had been to figure out ways to distribute ticks to targeted geographic areas.) But like Burgdorfer, he stopped short of providing specifics.

Were these two men seeking to clear their consciences for the roles they played in bioweapons research? Their generation of scientists is dying off. Is anyone left who might offer clarity? Are there any still-classified documents that hold the secrets?

Repairing the Open Wound

Newby’s book raises important questions that deserve answers. Chief among them: precisely what was done to weaponize Lyme disease—and why won’t the government come clean about it?

Lyme and other tick-borne pathogens are spreading throughout the world. In the U.S. alone, the number of people suffering from Lyme disease is projected to hit 2 million in 2020.

Yet, for the last 40+ years, our government’s effort to solve the Lyme disease crisis has been lethargic at best. While the medical establishment minimizes their plight, patients have largely been left on their own to figure out (and pay for) Lyme-related medical care. Meanwhile, few research dollars have been devoted to finding more effective treatments.

Author: Kris Newby

Bitten: The Secret History of Lyme Disease and Biological Weapons is a wake-up call. It’s time to stop business as usual and prioritize the Lyme disease epidemic. Helping those who currently suffer and protecting coming generations both depend on it.

What also depends on it: the ability to heal the “open wound” of how Lyme disease has been treated, untreated, and mistreated, for far too long.

The following is an excerpt from Kris Newby’s book:

Bitten: The Secret History of Lyme disease and Biological Weapons.

Diving straight back into his work at the lab, he began by analyzing the hundreds of Ixodes ricinus tick samples he’d brought home from Switzerland, searching for what was making the goatherds sick. He and the Swiss team found three microbes never before seen in this species of tick: an unidentified spotted fever rickettsia; a whip-tailed cattle protozoan similar to babesia, called Trypanosoma theileri; and the infectious larval stage of a parasitic deer worm, Dipetalonema rugosicauda.5

Willy sat at his microscope late into the night, snipping off tick legs and letting drops of their hemolymph fall onto a glass slide; mixing the drops with a stain that would make the rickettsias glow under a dark field microscope; and dissecting tick parts to see where the rickettsias hid inside the tick. Most established rickettsias evolve over time to find species-specific, competition-free niches within a tick.

But these rickettsias were everywhere, shimmering stars in Willy’s microscopic galaxy. They floated in the tick’s main body cavity, in the cell cytoplasm and nuclei, in the ovaries, and in all stages of tick sperm. It was worrisome. If the new organism could be transmitted from tick eggs to the thousands of newly hatched larvae, it would spread more rapidly into the ecosystem than most tick-borne diseases.

Under a higher magnification, Willy saw that the rickettsias existed in two form factors: a two-cells-fused-together (diplococcus) form and a sausage-like (rod) form. Both looked exactly like the newly discovered rickettsias he’d found on Long Island.

Willy began infecting lab animals with the Swiss rickettsias, and none of them got sick, but when he infected wild-type male meadow voles, a short-tailed species in the mouse family, they all came down with an infection of their testicular membrane sacks. On December 3, 1978, Willy nicknamed the new rickettsia from Switzerland “the Swiss Agent,” and wrote to Aeschlimann: “The organism is a bona fide rickettsia of the spotted fever group but quite different from Rickettsia rickettsii, R. sibirica, R. slovaca, and R. conorii,” he added, referring to the most virulent rickettsias.

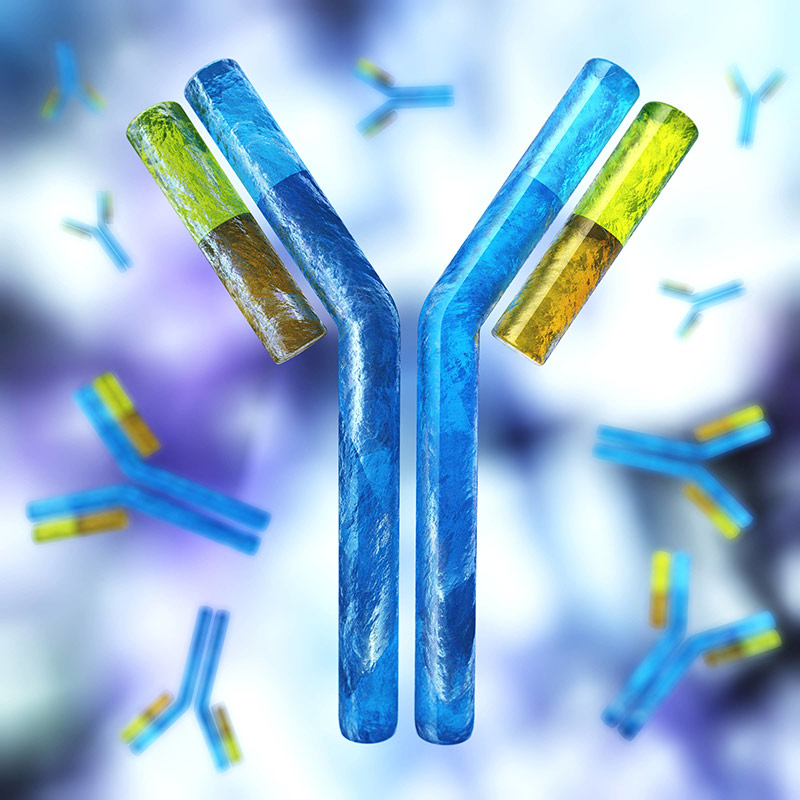

Next, he developed a fluorescent antibody test so that he could rapidly detect infected ticks, lab animals, or humans. First, he isolated a unique, identifying molecule from the surface of the microbe, labeled it as antigen C9P9, and mass-produced it in a flask filled with a growth medium. (Antigens are the “bad guys” to an immune system, and antibodies are essentially the beat cops on the lookout for them.

When antibodies bump into an invading germ’s surface antigen, they bind to it, essentially placing a “Most Wanted” poster on it. They also send out a biochemical all-points bulletin to other parts of the body, with instructions to destroy the germ.) Next, he smeared the C9P9 antigen on a microscopic slide and added a drop of an animal’s bodily fluids that had been mixed with a fluorescent dye. If the animal had recently been exposed to the germ, there would be antibodies that recognized C9P9 as an invader, and the dyed antibodies attached to the C9P9 antigens would glow like little neon lights under the ultraviolet illumination. That’s how Willy would know that the animal had been infected.

When antibodies bump into an invading germ’s surface antigen, they bind to it, essentially placing a “Most Wanted” poster on it. They also send out a biochemical all-points bulletin to other parts of the body, with instructions to destroy the germ.) Next, he smeared the C9P9 antigen on a microscopic slide and added a drop of an animal’s bodily fluids that had been mixed with a fluorescent dye. If the animal had recently been exposed to the germ, there would be antibodies that recognized C9P9 as an invader, and the dyed antibodies attached to the C9P9 antigens would glow like little neon lights under the ultraviolet illumination. That’s how Willy would know that the animal had been infected.

On April 12, 1979, he quietly began testing Lyme patients’ blood samples against the European Swiss Agent antigen and known disease-causing rickettsias. The blood samples reacted strongly only to the Swiss Agent antigen. This meant that the rickettsias from Switzerland and Long Island might be one and the same species or perhaps closely related.

With the discovery of the Lyme spirochete still two years away, Willy kept pursuing a hypothesis that the Lyme outbreak was caused by the same organism that was making the Swiss goatherds sick. By August 1980 he was confident enough with his experiments to share the test results with the East Coast investigators working on the disease outbreaks: John Anderson and Lou Magnarelli, from the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station; Jorge Benach, from the New York State Department of Health; and Allen Steere, from Yale University.

With the discovery of the Lyme spirochete still two years away, Willy kept pursuing a hypothesis that the Lyme outbreak was caused by the same organism that was making the Swiss goatherds sick. By August 1980 he was confident enough with his experiments to share the test results with the East Coast investigators working on the disease outbreaks: John Anderson and Lou Magnarelli, from the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station; Jorge Benach, from the New York State Department of Health; and Allen Steere, from Yale University.

In his lab notes he referred to “Swiss Agent USA” as an “R. montana–like rickettsia organism” or the “East side agent.” More blood and ticks were tested during the fall to make absolutely sure that this was the microbial culprit.

“I am excited to pursue further the possibility of a rickettsia etiology of Lyme disease,” Allen Steere wrote to Rocky Mountain Lab’s director, Robert N. Philip, on November 8, 1979. During the first quarter of 1980, the thrill of discovering a new disease started creeping into their correspondence. If it was true that the American Swiss Agent caused the Lyme outbreak, they’d go into the medical history books. Their finding would probably lead to tenure-track positions at a major university and a steady flow of research grants. They might even have a shot at a Nobel Prize.

On January 3, Willy wrote to Aeschlimann about testing he’d done on the Lyme arthritis patients: “I have done some preliminary serology with sera from patients and have found very strong reactions against the ‘Swiss Agent.’”6 In February, his phone log read, “Steere patient sera tested again: Still very positive for Swiss Agent.” In March, he wrote to Anderson and Steere again: “Most specimens, with a few exceptions, reacted only against antigens prepared from the Swiss Agent.”7 In short, the disease clusters in Connecticut and Long Island seemed to have been caused by Swiss Agent USA.

Then, in April, the Swiss Agent USA rickettsia vanished. It was never again mentioned in talks, letters, interviews, or journal articles. The only clue to its demise was a cryptic note from Steere to Willy that read, “As mentioned in our telephone conversation, enclosed are the decoded results of serological tests against various rickettsia . . . I appreciated the chance to talk with you yesterday about the future directions for this work . . . I agree that any plans for manuscript writing are currently premature. I would not want anything in print that you would not find convincing.”

Reading between the lines, it appears that Willy told Steere and Magnarelli that the Swiss Agent testing was unreliable. Benach recalls that Willy told him that he thought the new rickettsia was a harmless symbiont that didn’t cause disease.

And about two years later, Willy announced that a spirochete was the causative agent of Lyme disease. Case closed.

There is, without a doubt, something suspicious about the sudden disappearance of the Swiss Agent USA from all correspondence.

None of the living researchers involved in the Swiss Agent discovery seem to recall or know why exactly it fell off the radar. Its absence from the scientific literature is equivalent to the missing eighteen and a half minutes from Nixon’s White House tapes. And it leaves us with the important question: Why?

Editor’s note: Any medical information included is based on a personal experience. For questions or concerns regarding health, please consult a doctor or medical professional.