Yesterday, I was honored to speak at the US Department of Health and Human Services’ Lyme Innovation Roundtable, about the need to build the research capacity of Lyme patients to create sustainable change and accelerate Lyme disease research.

To do this, we must embrace big data, precision medicine, and patient-centered research. You can watch a video of my presentation below.

Good morning. I'm delighted to be able to present to you today. Lymedisease.org has been collecting patient-generated information in big data surveys for over 10 years, and our patient registry, MyLymeData, has enrolled over 12,000 patients so far. What I want to talk about today is how given the grindingly slow pace of traditional research in Lyme disease and the inaction of most policy makers, it has become essential that we build the Lyme disease research capacity of patients and develop the levers to create sustainable change, and accelerate research. To do this, we must embrace big data, precision medicine, and patient-centered research.

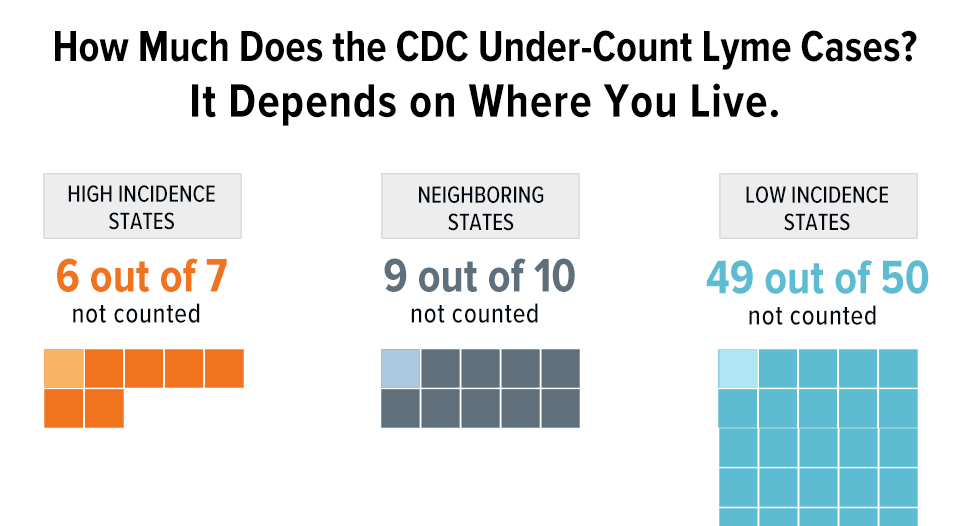

So this chart, which is derived from an article by Goswami, compares the number of clinical trials conducted in different infectious diseases. And what you see is this enormous research gap between Lyme and other infectious diseases. So let me put this in context. The CDC estimates that there are over 300,000 cases of Lyme Disease each year, that's eight times the number of new HIV/AIDS cases each year. But while HIV/AIDS holds the number one slot on the chart with the most research studies, Lyme disease trails behind leprosy. Which, you know, if you google leprosy, one commonly asked question is, "Does it exist in the United States any longer?" And it does, but there are only 200 new cases a year. So really just no comparison, in terms of the magnitude, 300,000 cases of Lyme disease, and the research funding that's being provided.

And the last clinical trials for the treatment of late/chronic Lyme disease was funded over 15 years ago with no new Lyme disease research in the pipeline. We are not even addressing the most basic questions like, how many patients with late or chronic Lyme disease were not diagnosed early when the treatments work the best? Or can we identify a subgroup of patients who are high treatment responders like they do in cancer and tuberculosis and learn from their success? But if you don't fund, you don't find. So we need to make funding clinical research in Lyme disease a priority and to fund it proportionately to its prevalence and incidence.

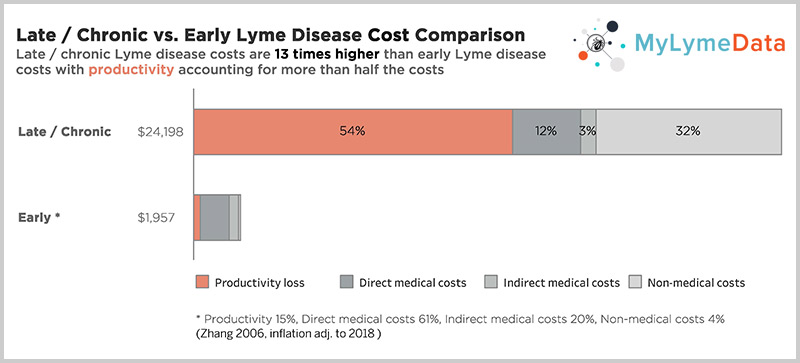

And we need to address the two most urgent research needs in Lyme disease: Preventing people from developing late/chronic Lyme disease and curing those who do. 70% of those in the MyLymeData registry were not diagnosed until at least six months after symptom onset. That means they have late Lyme disease. Treatment approaches developed decades ago leave too many patients ill. 35% in Aucott's study had persisting symptoms after treatment of early Lyme and those diagnosed late have far greater treatment failure rates. These patients remain ill and most in our surveys report being ill for 10 or more years until they are cured or die. And generally, this isn't a disease that kills most patients, it just makes them wish they were dead and robs them of their ability to be productive members of society for a long, long time. And this makes it a costly problem to ignore.

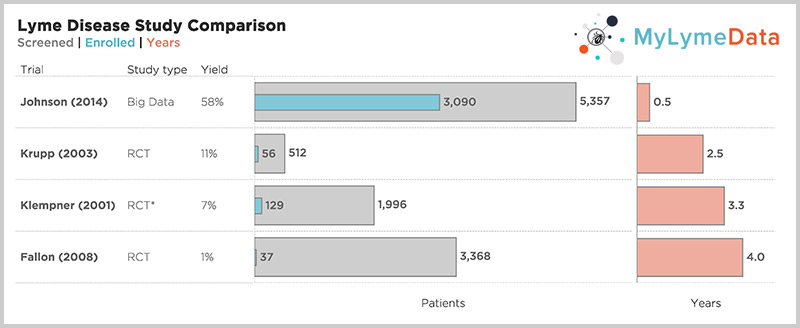

According to a CDC study, the cost of late/chronic Lyme disease is 12 times higher than the cost of treating early disease, about $24,000 per person per year when adjusted for inflation. And the traditional way of doing research, one sequential randomized controlled trial followed by another takes too long, costs too much, and doesn't apply to most people. As Rob Gale at the FDA points out, Janet Woodcock also at the FDA takes it a step further, at a recent industry panel saying, "I believe the clinical trial system is broken. I do not believe it serves the interests of patients." The NIH funded trials took 2.5 to five years to complete recruitment alone. And most patients were screened out. For example, in Klempner, they screened out 97% of those who applied. But look at the top bar, one of our published studies where it took six months to recruit over 3000 patients.

So today with big data, we can and must accelerate the pace of clinical research and include real world patients. But it's important to recognize that research orphaned diseases like Lyme disease require more targeted concerted research efforts. It requires that Lyme community shoulder more of the research burden early on by collaborating with others to build the knowledge base, identify biomarkers, and treatment endpoints. And this approach accelerates the research process so that industry is stepping into the disease later in the process, when many of the challenges have been identified and resolved. This de-risks the investment of time and money that the industry must expend to develop better diagnostics and more effective treatments.

Dr. Stephen Groft, who until his recent retirement a few years ago, headed the Office of Rare Disease Research for the NIH, shows us how to develop a research engine. In his process, patient registries play a vital role by linking with biorepositories, helping develop the disease knowledge base, shaping clinical trial hypotheses, speeding up recruitment times, expediting FDA approval, and reducing the burden of post-approval studies. Patient registries play a pivotal role in Groft's research engine because patients have access to sources of information that other stakeholders do not.

They are the monkeys in the middle who hold the key to unlocking data silos such as electronic health records, insurance records, biorepository sample results, lab results, and of course the information that can only be gleaned from patients, their symptoms, and their response to treatment. So the bottom line is that patients have more complete information about their health than any other stakeholder. And as Eric Topol, Editor-in-Chief at Medscape, points out, given the appropriate tools, patients represent the true blockbuster potential for improving outcomes. So Lyme disease has been connecting big data research using patient-generated data for over 10 years. We published our first study and Access to Care in 2011 and in 2014 we published our Quality of Life study.

In 2015, we launched MyLymeData, our patient registry and research platform, and with over 12,000 patients enrolled, today it is the largest observational study of Lyme disease ever conducted and actually one of the largest patient-driven registries in the nation for any disease. We have patients enrolled from every state in the nation and have collected over 2.5 million data points. We're collaborating with researchers from the University of Washington and from UCLA. The UCLA researchers were awarded a grant from the National Science Foundation to pursue their research in big data analytic techniques using data from the registry.

We have also collaborated with the National Disease Research Interchange, the leading source of research tissues in the nation, and with one of the sponsors of this conference, the Bay Area Lyme Foundation, on a tissue biorepository. And this type of collaboration is essential to build out a big data research engine and accelerate research in Lyme disease. This year we published our first study using registry data.

And as you can see, these efforts align with Groft's research engine components. The Lyme community now has a patient registry that is working with researchers and collaborating with the NDRI and BALF on a tissue biorepository toward a goal of identifying biomarkers for the disease. And I mentioned that we just published our first study based on data from the registry. The focus is on another component of the engine, the development of clinical treatment endpoints. So the outcome measure to determine success in past treatment trials for late/chronic Lyme disease has been average treatment response, but average treatment response is inherently flawed as an outcome measure because it ignores individual treatment response variation.

Think of it this way: If one person gets better and another gets worse, the responses cancel each other out on average. And other diseases like cancer and tuberculosis identify and learn from high treatment responders. They're called super-responders. But to do this, you need large samples and you need to be able to really hone in on individual treatment response variation at a highly granular level to identify different subgroups of patients and how they respond. So we used the widely validated outcome measure called the Global Rating of Change scale.

You simply ask a patient: "Would you say that since you started treatment, you are better, worse, or unchanged?" And those who said that they were better or worse are asked, "How much better or worse on a scale ranging from hardly better at all to a very great deal better?" And on average, there was not much treatment response for the group as a whole, but individual treatment response varied widely and because the sample was so large, close to 4000 and because the question was so granular, essentially a 15-point Likert scale, we could really look at treatment variation within subgroups. And this allowed us to identify a group of high treatment responders, about 34%, who reported improving moderately to a very great deal better.

Identifying high treatment responders is important so that we can learn from their success and look at the factors that may have contributed to their success, for example, time to diagnosis or type of treatment. And it is also the first step in moving Lyme disease towards personalized medicine and individualized care. So one key value of this Global Rating of Change scale outcome measure is that it can be asked by a patient registry, by a healthcare provider, or by a researcher in a controlled trial. This means that it can bridge different types of research and create interoperability of data which helps fuel the research engine we are trying to build to accelerate research in Lyme disease.

Let me conclude by saying that if you are a patient who is not enrolled in MyLymeData, please enroll today. Visit us at MyLymeData.org. If you are a researcher who wants to collaborate with us, please contact me directly. I want to thank the organizers for inviting me to present at this round table.

Unacceptably high treatment failure rates in Lyme disease

Unacceptably high treatment failure rates in Lyme disease and in early Lyme disease – roughly 35% in a 2013 study by Dr. Aucott-and even higher rates for those diagnosed late—mean that many patients remain ill. (Aucott 2013) In our published studies, patients with chronic Lyme disease report being ill for more than 10 years. (Johnson 2011)

In addition to the human toll this exacts, this also makes it a costly problem to ignore. According to a CDC study by Dr. X. Zhang the cost of late or chronic Lyme disease is 12 times higher than the cost of treating early disease —about $24,000 per person/per year when adjusted for inflation. (Zhang 2006)

And we can’t make the progress we need with the traditional way of doing research—one sequential randomized controlled trial followed by another. It simply takes too long, costs too much, and doesn’t apply to most people, as Dr. Rob Califf at the FDA often points out.

For example, the NIH funded Lyme trials took 2.5 to 5 years to complete recruitment alone and most patients were screened out. Hence, the Klempner study, screened out 97% of those who applied. But look at the top bar—one of our published studies—where it took 6 months to recruit over 3,000 patients. (Krupp, 2003; Klempner 2001; Fallon 2008; Johnson 2014)

Big Data and Lyme Disease Research

But it is important to recognize that research orphaned diseases—like Lyme disease—require more targeted concerted research efforts. It requires that disease communities shoulder more of the research burden early on by collaborating with others to build a knowledge base, and identify biomarkers and treatment endpoints. This approach accelerates the research process so that industry is stepping into the disease later in the process when many of the challenges have been identified and resolved. It also de-risks the investment of time and money that industry must expend to develop better diagnostics and more effective treatments.

Dr. Stephen Groft, who until his retirement a few years ago headed the Office of Rare Diseases Research for the NIH, tells us how to do this. In his process—patient registries play a vital role by linking with biorepositories, helping develop the disease knowledge base, shaping clinical trial hypothesis, speeding up recruitment times, expediting FDA approval and reducing the burden of post approval studies. (Groft 2014)

Patient Registries Play A Pivotal Role

Patient registries play a pivotal role in Groft’s research engine because patients have access to sources of information that other stakeholders do not. They are the monkeys in the middle who hold the key to unlocking data silos—such as:

- electronic health records,

- insurance records,

- biorepository sample results,

- lab results and

- of course, the information that can only be gleaned from patients—their symptoms and their response to treatment.

The bottom line is that patients have more complete information about their health than any other stakeholder, and as Eric Topol, Editor in Chief at Medscape points out “given the appropriate tools, [patients] represent [the] true “blockbuster” potential for improving their outcomes.”(Topol 2017)

MyLymeData – Largest Lyme Disease Study

LymeDisease.org has been conducting big data research using patient generated data for over 10 years.

We published our first study on Access to Care in 2011 and in 2014 we published our Quality of Life study. (Johnson 2011; Johnson 2014) In 2015, we launched MyLymeData, our patient registry and research platform. With over 12,000 patients enrolled, today, it is the largest observational study of Lyme disease ever conducted—and actually one of the largest patient driven registries in the nation—for any disease. We have patients enrolled from every state in the nation and have collected over 2.5 million data points.

We are collaborating with researchers from the University of Washington and from UCLA—the UCLA researchers were awarded a grant from the National Science Foundation to pursue their research using the data from the registry.

We have also collaborated with the National Disease Research Interchange–the leading source for research tissues in the nation–and with one of the sponsors of the HHS Lyme Innovation conference –the Bay Area Lyme Foundation on a tissue specimen biorepository. This is the type of collaboration that is essential to build out a big data research engine and accelerate research in Lyme disease. All of these efforts align with Groft’s research engine components.

First Lyme Disease Study Published Using Registry Data

This year we published our first study using registry data. This study focuses on another component of the engine—the development of clinical treatment endpoints

The outcome measure to determine success in past treatment trials for late/chronic Lyme disease has been the average treatment response. But average treatment response is inherently flawed as an outcome measure because it ignores individual treatment response variation. Think of it this way– if one person gets better and another gets worse, their responses cancel each other out– on average.

Other diseases—like cancer and tuberculosis—identify and learn from high treatment responders. They are called super-responders. But to do this you need large samples and you need to be able to really hone in on individual treatment response variation at a highly granular level to identify how different subgroups of patients respond.

We used a widely recognized validated outcome measure called the Global Rating of Change scale. You simply ask a patient: “would you say that since you started treatment you are better, worse, or unchanged?” Those who said they were better or worse, are asked how much better or worse on a scale ranging from hardly better at all to a very great deal better. “On average” there was not much treatment response for the group as a whole, but individual treatment response varied widely.

Because this sample was so large—close to 4,000 and because the question was so granular—essentially a 15 point scale—we could really look at treatment variation within subgroups. This allowed us to identify a group of high treatment responders—about 34%–who reported improving moderately to a very great deal.

Identifying high treatment responders is important in Lyme disease so that we can learn from their success and look at the factors that may have contributed to that success—for example, time to diagnosis or type of treatment.

It is also the first step in moving Lyme disease toward personalized medicine and individualized care.

Another key value of this global rating of change scale outcome measure is that it can be asked by a patient registry, by a healthcare provider, or by a researcher in a controlled trial. This means it can bridge different types of research and create interoperability of data—which helps fuel that research engine we are trying to build to accelerate research.

The promise of big data and patient-centered Lyme disease research

We are excited with the progress we have made with MyLymeData and the promise of big data and patient-centered research to accelerate the pace of research. We believe that Lyme communities need to build the components of an effective research engine by using MyLymeData, developing biorepositories, identifying biomarkers for the disease, compiling a knowledge base for the disease, and identifying clinical endpoints for trials that are relevant to patients. It is only by doing this that we can create the future that patients need in Lyme disease.

If you are a patient who is not enrolled in MyLymeData, please enroll today. If you are a researcher who wants to collaborate with us, please contact me directly.

The MyLymeData Viz Blog is written by Lorraine Johnson, JD, MBA, who is the Chief Executive Officer of LymeDisease.org. You can contact her at lbjohnson@lymedisease.org. On Twitter, follow her @lymepolicywonk.