“Pain scale” often inflicts extra pain on suffering patients

By Meg Huber

For six and a half years of my life, I was in the exact same situation nearly weekly—sitting in a doctor’s office being asked to rate my pain using a scale from 1-10.

The numbers were abstract while my pain, though ever-changing, was a concrete reality. How could I correlate what I was feeling in my body with a number on a scale?

When I was 10 years old, I started getting debilitating migraines. As time went on, I developed pain in my feet, muscles, joints, memory loss, loss of consciousness, and other debilitating symptoms. I was certain from the beginning that my pain was real and not just a figment of my imagination—like some medical professionals seemed to think.

However, because I did not have a name for my pain, I tried my hardest to keep it secret in case it was not real. Only my family saw glimpses of the pain I felt. There came a point in my life when I was practically bedridden, but I still masked my pain with a smile whenever I went out in public.

The specialists I had been going to no longer knew what to do with me, seeing as they had run all the tests, and nothing seemed out of the ordinary. They referred me to the pain management clinic with a life sentence of suffering and the hope that they would teach me how to live with it.

Delayed diagnosis of Lyme disease

Around this same time, a friend’s mother suggested I try one more doctor before giving up. Finally, this doctor listened, tested, and diagnosed me with Lyme, seven years after the onset of my symptoms. Unfortunately, my story of delayed diagnosis is not unique among those with Lyme.

Exactly half of my life has been marked by pain. Yet, I have been blessed to attempt and accomplish many things while being ill, something I know not all are granted due to their conditions. One of the great feats was attending college. I graduated from high school in May of 2020 and started classes at Southern Virginia University that fall.

Though I have had challenges, I have been able to face them and enjoy my time. My pain and experience with Lyme influences not only the personal decisions I make, but also plays a role in my education.

The pain scale

For a class last semester, I researched the history of the pain scale and its effect on patients.

I studied the scale in light of my own life experiences. Ultimately, I concluded that the pain scale in its present state needs major changes in order to provide useful information to doctors and create less mental anguish for patients. Doctors rely on patients’ ability to express what they are feeling, but the patients are not given the tools to do this effectively. Instead, they are hindered by the confines of a number.

The issues with the pain scale are two sided between medical professionals and patients. Patients have a responsibility to express the pain they are feeling but may not have the tools to do so. As novelist and poet Virginia Woolf says, “The merest schoolgirl, when she falls in love, has Shakespeare or Keats to speak her mind for her; but let a sufferer try to describe a pain in his head to a doctor and language runs dry.”

This inability to adequately describe pain causes tension between doctors, patients, and other support members. Medical professionals need to recognize how hard it is for patients to verbalize pain and help guide them to accurate descriptions.

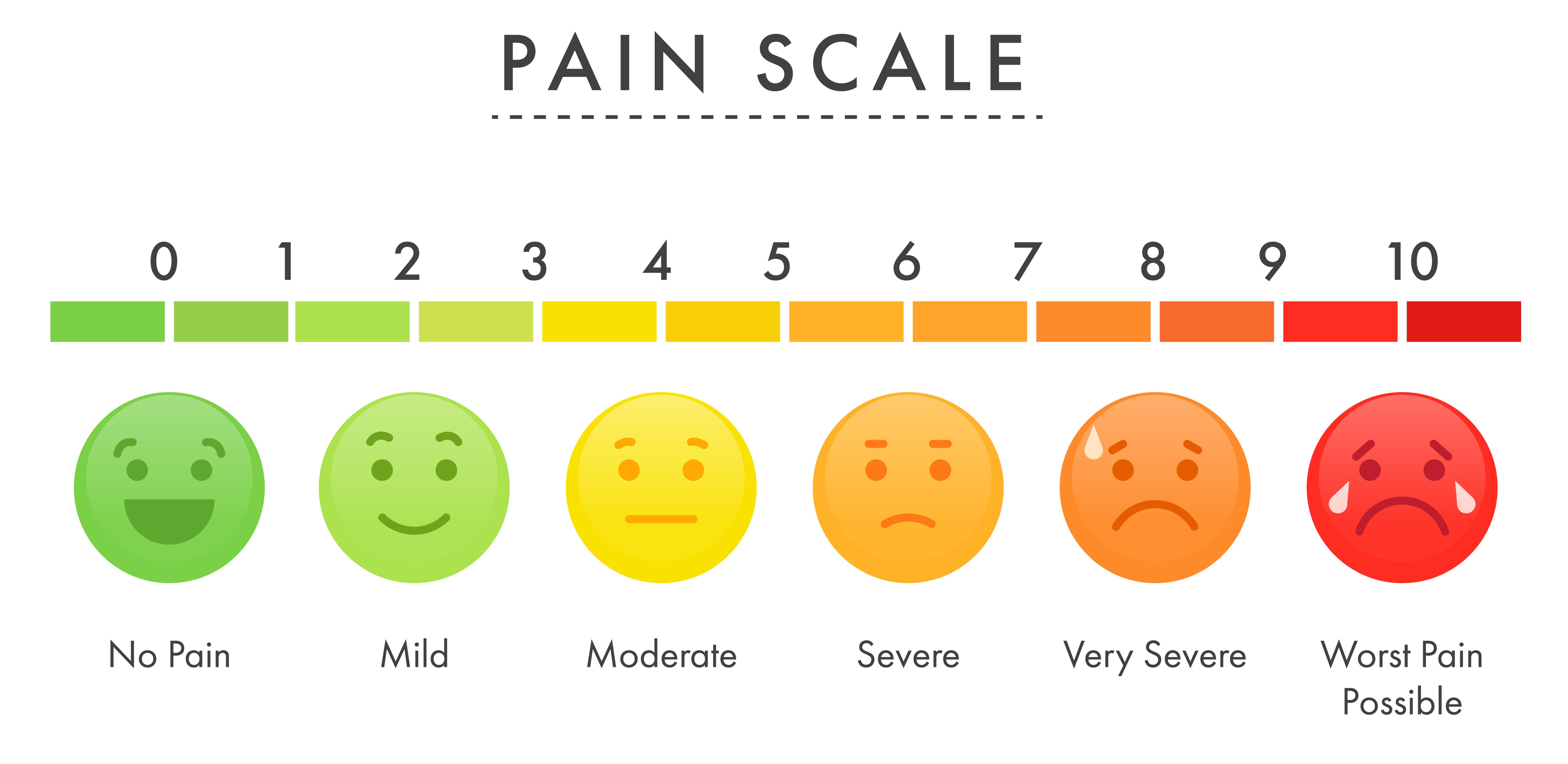

Typically, nurses use the scale during the intake portion of a doctor’s visit. The nurse shows you a chart and asks you to select the number or face that best matches your level of pain. It’s supposed to be a quick way for you to communicate and for the nurse to keep track of your response.

Though the scales offer quick measurements of pain levels, there is room for discrepancy on the recording of answers. Medical professionals have seen a lot of pain, which creates the potential for them to doubt what the patients say. It could be said that, since medical professionals have been around so much pain, they would have a better idea of the pain scale and could rank people’s pain based on symptoms or the way they looked and how they were handling pain.

But this eliminates the patient experience and disregards individual pain tolerance. The issue of pain tolerance is one of the largest factors with pain scales that seems to be overlooked by the medical community. Because people experience pain differently, they will rank pain differently, too. Therefore, pain is subjective and unratable.

Perception of pain

The perception of pain also has influence in associating numbers. When a child is first learning to walk, they often fall and hop back up. However, if parents make a big deal about the fall, the child may start to cry. The perception of being in pain, either by yourself or outsiders, may influence the level of pain you say you are in. This creates a disconnection from the actual pain you are feeling and the pain you think you should be feeling.

Furthermore, the perception of chronic and acute pain is different. Acute pain is quick and painful, and the immediacy of it can make the pain seem worse. The moment you fall off a bike and scrape your hands, you get instant pain that could be described as stinging or throbbing. The instantaneous nature of acute pain feels overwhelming and may lead to higher perception of pain and higher reported pain levels.

On the flip side, since chronic pain has been felt for so long, it muddies the ability to rank pain. Those in chronic pain expect to be in pain and see it as normal. They may feel that the healthcare professionals recognize that they are in pain, so the need to number it is arbitrary. Chronic pain patients have the added complexity of already feeling as if no one understands their pain and having to put a universal number on it perpetuates that idea.

Eliminate the pain scale?

Though I do not have a solution to this problem, I think we should eliminate the pain scale unless major education and changes are made to it.

Pain is not one-dimensional. It’s a mistake to believe that a number or expression can articulate what we are feeling. Asking multiple ways to describe pain is much more effective, though it still lacks in encapsulating the full pain.

The time taken to understand patient’s pain through creating a personal pain scale to use a ranking system and having them use words and pictures could create a greater sense of what they are feeling.

A scale also must be used for every part of pain they are in. With my specific condition, it’s not just my leg that hurts, it is my entire body. However, they all hurt in different ways and levels.

A scale needs to be created individually and with acute and chronic pain in mind. Experiences of pain are individual and vary on circumstances and the type of pain. Being asked what level of pain I am in creates more pain to me as a patient. This harm should be addressed and mitigated.

We invite you to comment on our Facebook page.

Visit LymeDisease.org Facebook Page