LYME SCI: Working Group’s report documents spread of infected ticks

The latest Tick-Borne Disease Working Group has submitted its 2020 Report to Congress. It represents thousands of hours of work over a two-year period.

It is divided into 11 Chapters plus a summary, conclusion and appendices totaling 177 pages and is available for download.

Chapters 3-8 highlight the combined work of the eight subcommittees appointed according to the priority areas identified by the Working Group.

These chapters are as follows:

Chapter 3: Tick Biology, Ecology, and Control

Chapter 4: Clinical Manifestations, Diagnosis, and Diagnostics

Chapter 5: Causes, Pathogenesis, and Pathophysiology

Chapter 6: Treatment

Chapter 7: Clinician and Public Education, Patient Access to Care

Chapter 8: Epidemiology and Surveillance

I’d like to draw attention to a few things from the subcommittee I served on—Tick Biology, Ecology and Control. Our final report to the Working Group was over 100 pages and needed to be condensed.

It was our job to pull from our subcommittee report the top three priorities which we felt needed to be included in the final Report to Congress. You can read our full report here: Tick Biology, Ecology, and Control Subcommittee Report to the Tick-Borne Disease Working Group

Note: Each of the eight subcommittee reports contain comprehensive information on tick-borne diseases. I highly recommend bookmarking this page and using these reports whenever you need up-to-date references.

Vector-borne disease

First, a little background on tick-borne diseases. Ticks fall into a broad category of living organisms that can transmit diseases between humans, or from animals to humans. Such organisms are known as vectors.

Most vector-borne diseases in humans are caused by parasites, viruses and bacteria transmitted by bloodsucking vectors like mosquitoes and ticks. Aquatic snails, blackflies, sandflies, fleas, bedbugs, and lice are other vectors of disease.

In the continental U.S., where mosquitoes are better controlled, ticks are now responsible for over 75% of all vector-borne diseases reported to the CDC annually. While Lyme disease accounts for over 80% of all tick-borne cases, spotted fever rickettsiosis, babesiosis, anaplasmosis and ehrlichiosis have also seen an increase over the past four decades.

Over the past five years, there have been only 30,000 to 42,000 annual cases that meet the CDC’s strict surveillance criteria for Lyme disease. However, based upon insurance data, the CDC now estimates the actual number of Lyme disease cases is 476,000 per year. (See: How much does the CDC undercount Lyme disease? It depends upon where you live.)

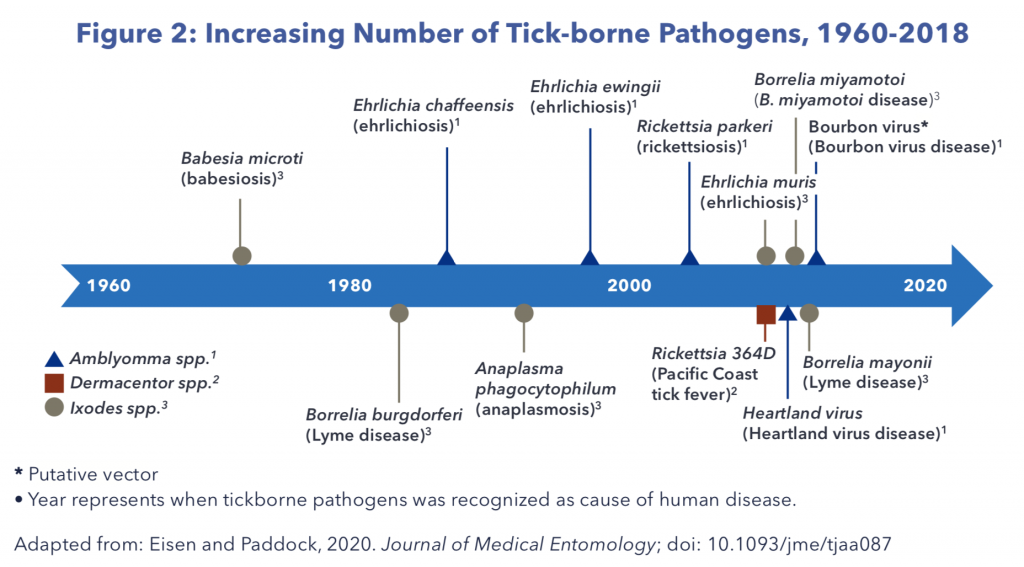

Increase of tick-borne pathogens

Not only are ticks expanding their regions, but the number of pathogens they carry are also increasing. From 1900 to 1960, there were only seven known tick-borne pathogens in the US. Since 1960, there have been 12 new pathogens discovered in the US, most of those in the past 20 years.

Several factors contribute to the increase in ticks and the pathogens they carry. Warming climate is a big one, but bird migration, increasing number of hosts (like deer and mice), deforestation and other factors also play a part.

Unlike mosquitoes, ticks are hard to control. For instance, you can treat your yard for ticks, but if your neighbors do not, that won’t solve the problem. In time, ticks will return to your yard again.

While mosquitoes can be targeted during the larval stage, where they require stagnant waters, tick breeding grounds are more diverse and difficult to pinpoint. Ticks can thrive and reproduce in forests, parks, private yards and even in household carpets and pet bedding.

For these complex reasons, my subcommittee attempted to lay out a plan to help monitor and slow the spread of tick-borne diseases in the U.S.

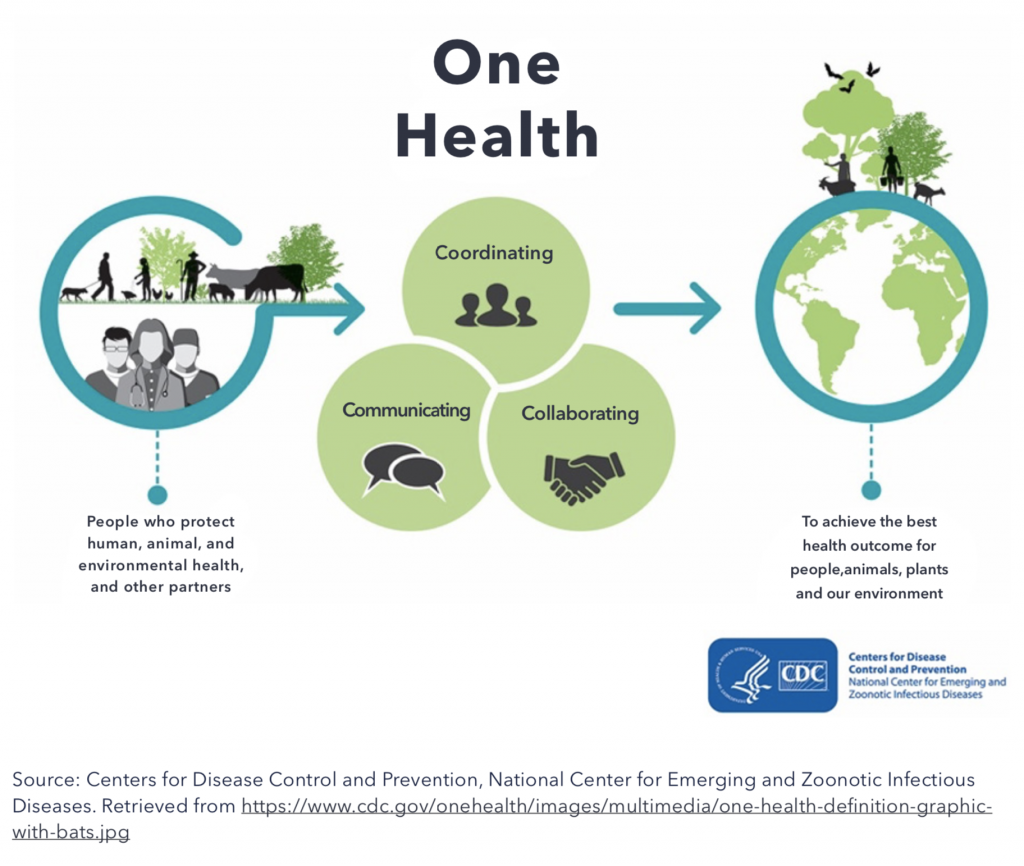

One Health Approach

Our first recommendation was to “Adopt a One Health Approach to Employ Integrated Tick Management and Exploit Ecological Weaknesses of Tick-borne Disease Systems.”

“One Health” is a concept that promotes collaboration among scientists from many different specialties to achieve the best health for people, animals, and the environment. For this reason, One Health teams include physicians, veterinarians, ecologists, and many others acting on regional, national and global levels to achieve optimum health.

Adopting a One Health approach will help facilitate the discovery of new tick control measures as well as integrating tick management across federal, state and local agencies. It will also encourage universities to get involved in surveillance and private companies to invest in research and development of tick-control products like Nootkatone.

Integrated Tick Management Strategies

Our second recommendation was to “Identify and Validate Integrated Tick Management Strategies.”

The integrated pest management (IPM) model is a sustainable, science-based, decision-making process that combines biological, cultural, physical and chemical tools to identify, manage and reduce risk from pests. For example, IPM is the method used in the U.S. to eradicate mosquito-borne diseases like malaria. To date, this broad scale integrated management strategy has never been applied against ticks.

New strategies may include targeting ticks at every life stage, treating deer with tick-oriented pesticides, anti-tick vaccines for deer or mice, mouse bait boxes, tick tubes and more. If adopted, these broad strategies would shift the burden of controlling ticks from individual homeowners to federal, state and local pest control agencies.

Another complicating factor: each species of tick has a different life cycle. For instance, Ixodes scapularis, the vector for Lyme disease on the East coast, has a two-year life cycle.

While the Western blacklegged tick (Ixodes pacificus,) the vector for Lyme on the West coast, has a three-year life cycle.

National Tick Surveillance

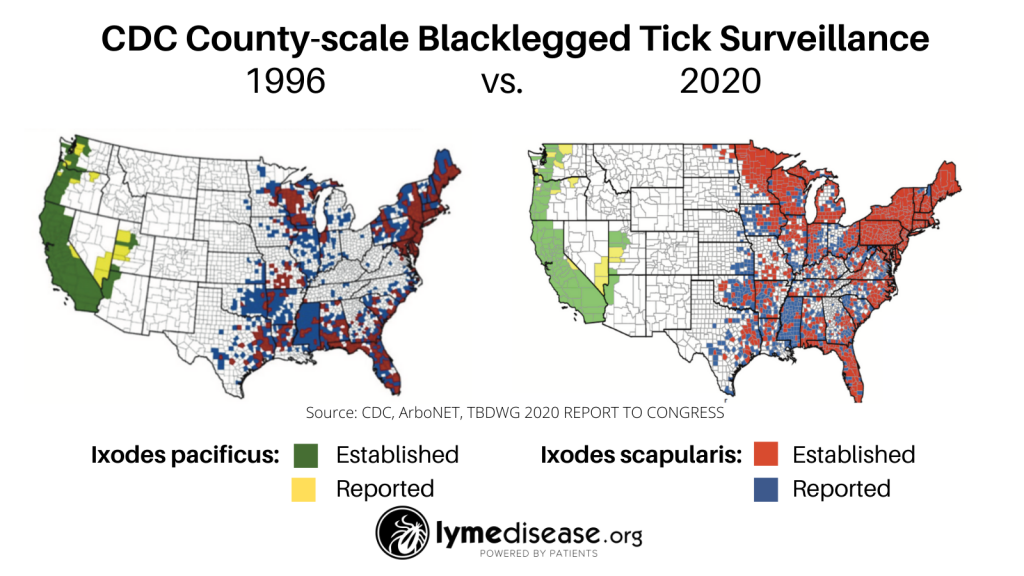

Our third priority was to “Build on the CDC National Tick Surveillance Framework.”

In its 2018 Report to Congress, the previous Working Group emphasized the need for national tick surveillance. One year later, the CDC took steps to initiate a national tick surveillance program. And in 2020, the CDC launched a new “National Public Health Framework for the Prevention and Control of Vector-Borne Diseases in Humans.”

Specifically, the CDC:

- Released surveillance guidance for two significant vectors of tick-borne diseases (blacklegged ticks and western blacklegged ticks),

- Increased financial investments to fund tick surveillance programs in 25 jurisdictions,

- Began pathogen testing of blacklegged and western blacklegged ticks submitted by state, local, and territorial health departments, and

- Established a system (ArboNET) that allows states to report findings directly to CDC for inclusion in the annual tick surveillance reports.

By comparing the 1996 ArboNET distribution map to the 2020 distribution map, you can easily see the spread of the blacklegged tick.

In addition to tracking the spread of the blacklegged ticks (Ixodes scapularis and Ixodes pacificus), our subcommittee recognized the importance of tracking other tick species and the pathogens they carry.

Another tick that has seen a marked increase in expansion is the lone star tick (Amblyomma americanum), the vector for several bacterial and viral diseases. The lone star tick is also associated with the newly recognized alpha-gal syndrome, which is also featured in the 2020 report to Congress.

Looking forward

My fellow subcommittee members were professional and easy to work with. However, they tended to focus on the east coast. I felt like I had to fight to have west coast ticks and the pathogens they carry represented in our report. Another thing that was somewhat disappointing was the strict criteria used for surveillance of ticks.

The new national surveillance criteria use a dragging and pathogen-testing technique that is strictly defined. It was explained to me that this strict definition reduces the chances of falsely inflating numbers.

Unfortunately, the ArboNET tick surveillance reporting method eliminates most university-led research and all citizen science, including the 16,000+ tick study conducted by Northern Arizona University in partnership with Bay Area Lyme Foundation.

The 2020 Report to Congress is the second of what will be three reports generated over a six-year period by three different Working Groups.

Nominations for the next panel were submitted in December. We’re waiting to see what happens next.

LymeSci is written by Lonnie Marcum, a Licensed Physical Therapist and mother of a daughter with Lyme. In 2019-2020, she served on a subcommittee of the federal Tick-Borne Disease Working Group. Follow her on Twitter: @LonnieRhea Email her at: lmarcum@lymedisease.org .

References

U.S. Department of Health & human Services: Tick-Borne Disease Working Group 2020 Report to Congress. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/tbdwg-2020-report_to-ongress-final.pdf

Rosenberg R, Lindsey NP, Fischer M, et al. (2018) Vital Signs: Trends in Reported Vectorborne Disease Cases — United States and Territories, 2004–2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6717e1

Amy C Fleshman, Christine B Graham, Sarah E Maes, Erik Foster, Rebecca J Eisen. (2021) Reported County-Level Distribution of Lyme Disease Spirochetes, Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto and Borrelia mayonii (Spirochaetales: Spirochaetaceae), in Host-Seeking Ixodes scapularis and Ixodes pacificus Ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) in the Contiguous United States, Journal of Medical Entomology, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/jme/tjaa283

Schwarz, A.; Kugeler, K.; Nelson, C.; Marx, G.; Hinckley, A. (2021) Use of commercial claims data for evaluating trends in Lyme disease diagnoses, United States, 2010–2018. Emerg Infect Dis. DOI: doi:https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2702.202728

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) | Tick surveillance https://www.cdc.gov/ticks/surveillance/index.html

CDC: Division of Vector-Borne Diseases | A National Public Health Framework for the Prevention and Control of Vector-Borne Diseases in Humans. https://www.cdc.gov/ncezid/dvbd/framework.html

We invite you to comment on our Facebook page.

Visit LymeDisease.org Facebook Page