LYME SCI: The ticks you don’t see are the most dangerous

Summer is here! It’s time for picnics, hiking and camping. As the weather warms, ticks will go into hiding. But just because you don’t see ticks doesn’t mean they aren’t there. In fact, the ticks you don’t see are the most dangerous.

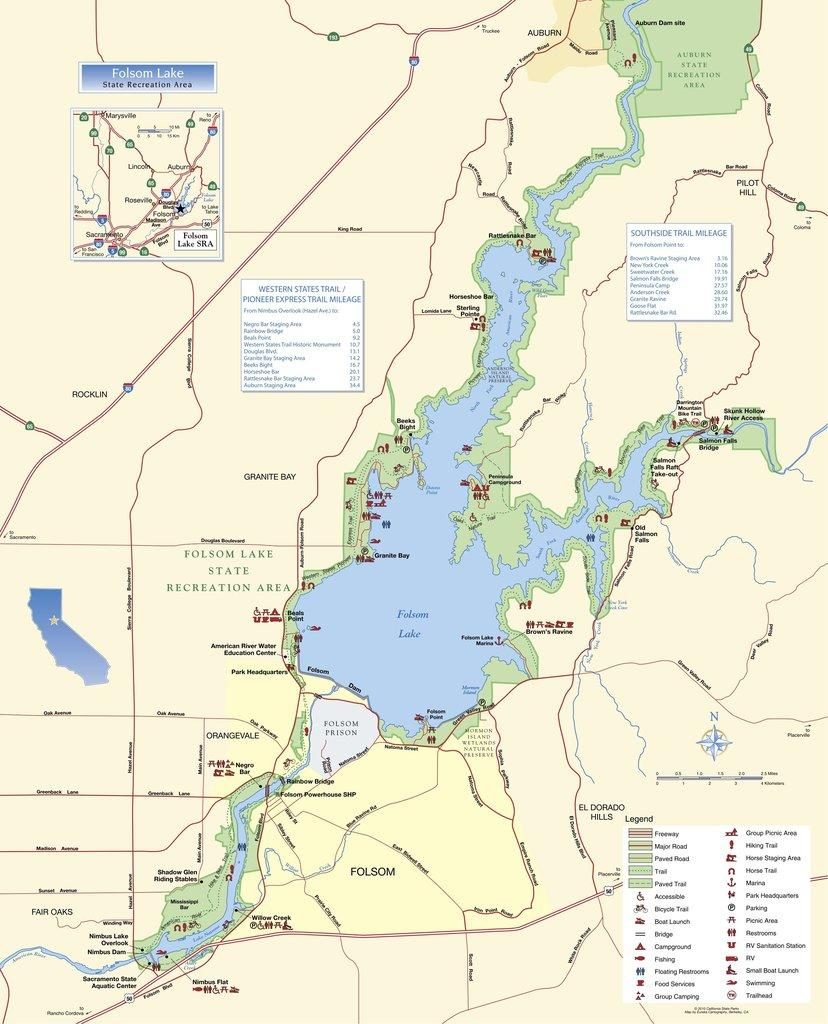

A new tick study looks at environmental and behavior patterns of nymphal ticks in the Sierra foothills of California. (Hacker, 2021)

Over a three-year period, researchers collected more than 2,000 ticks from Folsom Lake State Recreation Area. It’s a popular spot for outdoor enthusiasts, about 20 miles northeast of Sacramento.

Rocks, logs and tree trunks

The study team didn’t limit their investigation to leaf litter, where researchers typically look for nymphal ticks. They also searched for ticks on rocks, logs, and tree trunks, in an effort to better understand seasonal and environmental factors affecting ticks.

They collected more nymphal ticks than they had expected. And believe it or not, they found the highest percentage of Lyme-infected ticks on rocks!

Overall, they found the prevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi (the bacteria that causes Lyme disease) in Ixodes pacificus (western blacklegged tick) nymphs was 6.2%. However, this varied greatly by season and year. Seasonally, nymphal tick activity peaked from March through June.

During one year, the average infection rate of nymphal ticks exceeded 11%. Then it dropped to 2% the following year. The highest rate of infected ticks occurred after the rainy season and in areas shaded by trees.

The lowest rate of infected ticks occurred after periods of prolonged drought, higher temperatures (above 21-23º C, 70-73º F.), and lower humidity (below 83–85%.)

Blacklegged ticks (Ixodes scapularis, Ixodes pacificus) transmit Borrelia burgdorferi, the bacteria that causes Lyme disease. They have four lifecycle stages—egg, larva, nymph and adult—the last three being able to bite and transmit disease to humans.

As it turns out, the standard dragging techniques are not necessarily the best method for finding nymphs outside of the northeastern US. (Tietjen, 2020). As a result, nymphal ticks have gone largely undetected in many regions of the country. This includes many parts of California that have rarely, if ever, been sampled.

West coast Lyme puzzle

In California, nymphal ticks have a higher Lyme-infection rate than adult ticks. This is the opposite of the East coast, where the greatest risk of infection comes from mature ticks.

Ticks are not born with the bacteria that causes Lyme disease—they acquire it by feeding on an infected animal, known as a host. In the eastern US, the primary reservoir host for Lyme disease is the white-footed mouse.

In the western US, the primary reservoir host for Lyme disease is the Western gray squirrel. Immature ticks typically acquire the pathogen when they feed on an infected squirrel. When the infected tick matures and then feeds again, it can pass the bacteria on to the next animal or human.

There is another unique feature to the Lyme disease puzzle on the West coast, the Western fence lizard.

In 1998, a groundbreaking study by UC Berkeley entomologist Robert Lane brought this issue to light. He found that if an infected Western blacklegged tick feeds on a Western fence lizard, a protein in the blood of the lizard neutralizes the Borrelia bacteria in the gut of the tick. (Lane, 1998)

This results in a unique phenomenon where nymphal ticks have a higher infection rate than adult ticks. This is important, as up to 90% of the juvenile Western blacklegged ticks will feed on the Western fence lizard.

As previous studies have shown, northern California has the highest rate of Lyme disease in the state. In Mendocino and Humboldt counties, for instance, the nymphal tick infection rate can be as high as 40%. (Tälleklint-Eisen,1999)

Meanwhile, a more recent study found tick infection rates of up to 31% in some parts of the San Francisco Bay Area. (Salkeld, 2021)

“Average” is misleading

This study highlights the great diversity of tick abundance in California. When you average tick infection rates across the whole state, you get an average infection rate of 1%. But that gives a misleading picture.

It’s important to recognize that the risk for tick-borne disease is not uniform throughout the state (or even within a county), and that nearly invisible nymphal ticks are the primary culprit for Lyme disease.

These tiny nymphal ticks are as small as poppy seeds. Imagine going for a hike and trying to spot a poppy seed before sitting on a rock or log.

So this summer, as you plan your outdoor activities, be sure to include tick protection in your to-go bag. Oh, and watch where you sit!

LymeSci is written by Lonnie Marcum, a Licensed Physical Therapist and mother of a daughter with Lyme. In 2019-2020, she served on a subcommittee of the federal Tick-Borne Disease Working Group. Follow her on Twitter: @LonnieRhea Email her at: lmarcum@lymedisease.org.

References

Hacker G.M., Jackson B.T., Niemela M., Andrews E.S., Danforth M.E., Pakingan M.J., Novak M.G. (2021) A Comparison of Questing Substrates and Environmental Factors That Influence Nymphal Ixodes pacificus (Acari: Ixodidae) Abundance and Seasonality in the Sierra Nevada Foothills of California. J Med Entomol. Apr 16:tjab037. doi: 10.1093/jme/tjab037. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 33860326.

Lane, R., & Quistad, G. (1998). Borreliacidal Factor in the Blood of the Western Fence Lizard (Sceloporus occidentalis). The Journal of Parasitology, 84(1), 29-34. doi:10.2307/3284524

Lane, R. S., J. Mun, M. A. Peribáñez, and H. A. Stubbs. (2007) Host-seeking behavior of Ixodes pacificus (Acari: Ixodidae) nymphs in relation to environmental parameters in dense-woodland and woodland-grass habitats. J. Vector Ecol. 32: 342–357.

Rose, I., Yoshimizu, M. H., Bonilla, D. L., Fedorova, N., Lane, R. S., & Padgett, K. A. (2019). Phylogeography of Borrelia spirochetes in Ixodes pacificus and Ixodes spinipalpis ticks highlights differential acarological risk of tick-borne disease transmission in northern versus southern California. PloS one, 14(4), e0214726. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0214726

Salkeld D.J., Lagana D.M., Wachara J., Porter W.T., Nieto N.C. (2021) Examining prevalence and diversity of tick-borne pathogens in questing Ixodes pacificus ticks in California. Appl Environ Microbiol. Apr23:00319-21. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00319-21.

Tälleklint-Eisen L, Lane RS. (1999) Variation in the density of questing Ixodes pacificus (Acari:Ixodidae) nymphs infected with Borrelia burgdorferi at different spatial scales in California. J Parasitol. Oct:85(5):824-31. PMID: 10577716.

Tietjen, M., Esteve-Gasent, M. D., Li, A. Y., & Medina, R. F. (2020). A comparative evaluation of northern and southern Ixodes scapularis questing height and hiding behaviour in the USA. Parasitology, 147(13), 1569–1576. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003118202000147X

We invite you to comment on our Facebook page.

Visit LymeDisease.org Facebook Page