LYME SCI: Early diagnosis necessitates Lyme-savvy doctors

The following are my written comments to the ninth meeting of the Tick-borne Disease Working Group (TBDWG) on June 4, 2019.

Dear Members of the Tick-Borne Disease Working Group:

My name is Lonnie Marcum. I am a physical therapist in California. Seven years ago, I had to quit work to take care of my 14-year-old daughter after she came home from school with flu-like symptoms and never got better.

Nearly a year later, she received a positive test for Ehrlichia chaffeensis. That led us to discovery of other vector-borne infections, including Lyme disease and Bartonella. At the time, I knew nothing about tick-borne infections, so when her doctor gave her a 21-day supply of doxycycline, I thought she’d be better in 21 days.

I was wrong.

Years later, after tediously treating each of her infections and repairing her immune system, she gradually began to get her health back. And today I am happy to say she is about 80% better.

Since my daughter’s illness began, I have found a new purpose—to find a cure for Lyme and co-infections. I am now a science writer for LymeDisease.org, one of the most trusted sources of information for patients with Lyme disease. There I devote my time to reading current research, interviewing scientists and sharing what I’ve learned through my blog LYME SCI.

What I’ve learned is that there are a lot of misconceptions about Lyme disease. First, that it is easy to diagnose, and second that it is easy to treat. Nothing could be further from the truth, in my opinion.

Early diagnosis is key

While it may be true that many patients who receive early diagnosis and early treatment do get better, a huge percentage of patients DO NOT receive an early diagnosis. In fact, fewer than 12% of the 12,000 patients in LymeDisease.org’s patient registry, “MyLymeData,” received a diagnosis within the first month after the tick bite. (Johnson 2019)

Delayed diagnosis is critical to understanding why so many patients are left with debilitating symptoms after standard treatment for Lyme. During the months to years that patients are suffering, the untreated infection spreads throughout the body, embedding itself deeply into connective tissues where standard antibiotics have a hard time reaching. (Embers 2012, Cabello 2017, Caskey 2015)

One study demonstrated that a delay in treatment by as little as 9-19 days is predictive of persistent Lyme symptoms. (Bouquet 2016)

Think of these untreated infections like a leaky roof. If you can stop the leak and mop up all the water the first day, the structure will probably be fine. But if you wait a week, a month, a year or more, the damage seeps into the roof, the walls, and the floor, causing mold and rot. If you catch it early enough you may only need to replace the drywall and paint. But if it goes deeper, the structure may need to be replaced.

This is exactly what happens with Lyme patients. Some are lucky to be treated early and recover completely.

Unfortunately, the majority of patients, like my daughter, are initially misdiagnosed with another illness and go months or years before receiving a proper diagnosis. During this time the infection(s) spread to the organs, the brain, the bone marrow, and the heart. (Coughlin 2018, Novak 2019)

Treatment failure is high

Unfortunately, there is no standardized treatment for this patient population. The last NIH-funded treatment trial for patients with persistent Lyme disease was over 10 years ago and it did not reveal a solution. (Fallon 2008, Goswami 2013) The latest study out of Johns Hopkins University found that a triple-drug combination was the only method successful in eradicating the infection in mice. (Feng 2019)

The other issue is that ticks can carry multiple pathogens that can infect people at the same time. (Moutailler 2016) In the MyLymeData survey of patients with chronic symptoms of Lyme disease, over 50% had multiple infections (also known as co-infections).

The most common co-infections are Babesia, Bartonella, Ehrlichia, Mycoplasma, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, Anaplasma and tularemia—all pathogens that can be transmitted by ticks. (Johnson 2014)

The issue with many of these co-infections is they are not all treated with the same prescription medication as Lyme disease. For instance, a patient may receive a diagnosis of Lyme and start taking the appropriate antibiotic, but they may also have an undiagnosed babesia infection which requires an anti-parasitic medication.

As a result, this patient may not get better until all the infections are treated properly. Unfortunately, there are no clinical trials on the most effective method to treat patients with multiple infections.

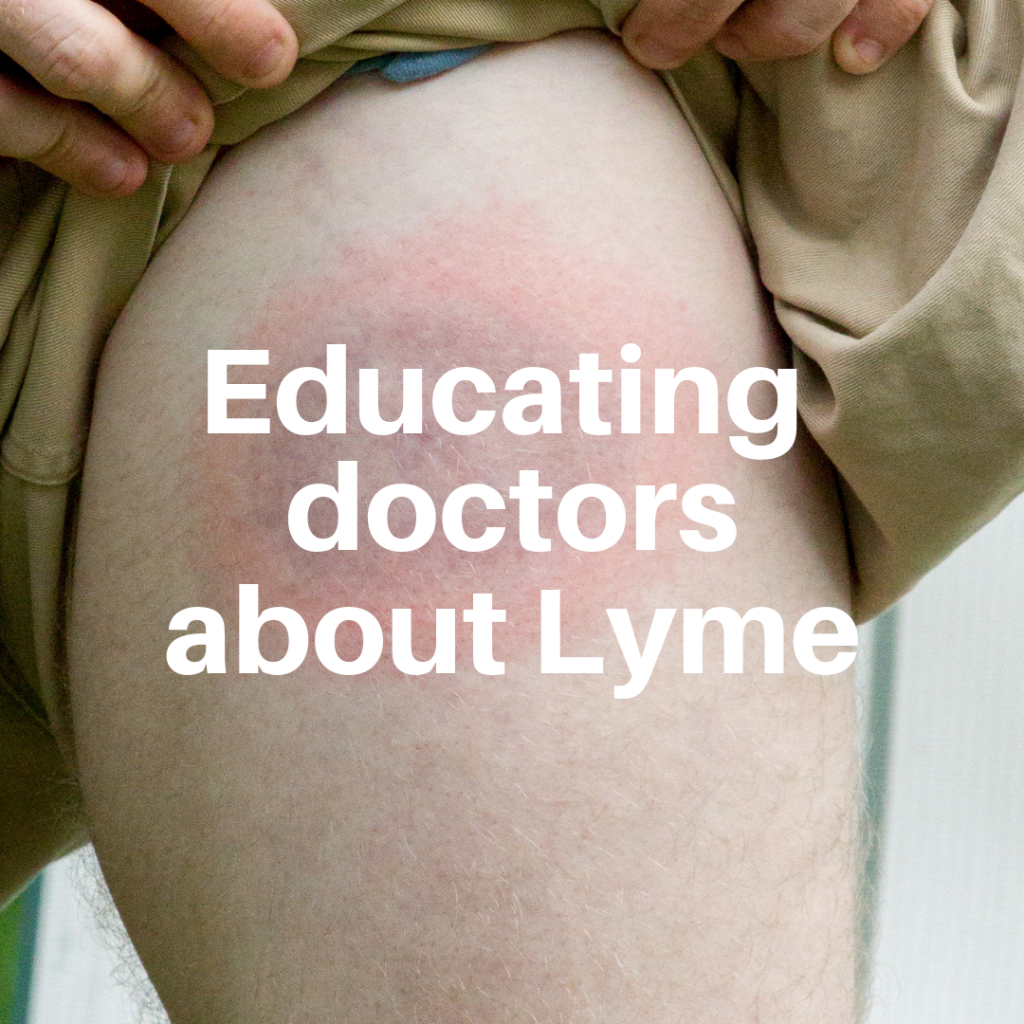

Need for physician awareness and education

This brings me to my final point—delayed diagnosis of tick-borne diseases. In my opinion, there are two things contributing to the large number of missed diagnoses of Lyme and other tick-borne diseases. 1) lack of physician awareness and education, and 2) lack of accurate diagnostic tools. (Cook 2016)

For example, I know a patient who just last week went to her doctor with a distinctive bull’s-eye shaped rash. Her doctor refused to give antibiotics because her test for Lyme was negative.

Even though the CDC clearly states, “Lyme disease is diagnosed based on: signs and symptoms, and a history of possible exposure to infected blacklegged ticks,” this physician refused to treat this woman during the critical early phase of infection. This is clearly an example of a lack of physician awareness and education.

The second issue here is that the standard test for Lyme is designed to detect antibodies that may take 4-6 weeks for the patient’s immune system to produce. (Borchers 2015) So, while I fault the physician for not knowing about the inaccuracy of the test in the early phase, I also fault the CDC for allowing a faulty test to remain on the market.

To summarize my recommendations:

- Improve physician education and awareness of Lyme and tick-borne diseases at all state and local levels. You might do this by requiring doctors to participate in at least one tick-borne disease continuing medical education (CME) course in order to renew their license.

- Reduce the number of missed diagnosis and misdiagnoses for Lyme and other tick-borne diseases by developing a precise test capable of detecting all pathogens in a single test.

- Improve treatment success rates for patients with late-stage Lyme disease. You may do this by designing clinical trials that use combination antibiotics proven successful in animal models.(Feng 2019)

Thank you for the opportunity to submit comments to the Tick-Borne Disease Working Group (TBDWG). I was an avid viewer of the first eight meetings of the TBDWG and am very happy with the final versions of the sub-committee reports and the Report to Congress. I find them to be some of the most comprehensive accumulations of information regarding tick-borne disease on record.

I look forward to following the second session of the TBDWG and hope that you are able to help implement some of the recommendations as proposed in the first TBDWG Report to Congress.

LYME SCI is written by Lonnie Marcum, a physical therapist and mother of a daughter with Lyme. Follow her on Twitter: @LonnieRhea Email her at: lmarcum@lymedisease.org .

References

Aucott JN, Rebman, AW. Crowder, L.A.; Kortte, K.B. (2013) Post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome symptomatology and the impact on life functioning: Is there something here? Qual. Life Res. 2013, 22, 75–84. doi: 10.1007/s11136-012-0126-6

Bouquet J, et al (2016) Longitudinal Transcriptome Analysis Reveals a Sustained Differential Gene Expression Signature in Patients Treated for Acute Lyme Disease. Am Society Micro. DOI: 10.1128/mBio.00100-16

Borchers A, et al. (2015) Lyme disease: A rigorous review of diagnostic criteria and treatment. J Autoimmun. 2015 Feb;57:82-115. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2014.09.004

Cabello FC, Godfrey HP, Bugrysheva JV, Newman SA. (2017) Sleeper cells: the stringent response and persistence in the Borreliella (Borrelia) burgdorferi enzootic cycle. Environ Microbiol 19(10):3846-3862, 2017. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13897

Caskey JR, Embers ME. (2015) Persister Development by Borrelia burgdorferi populations in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59(10):6288-6295, 2015. DOI: 10.1128/AAC.00883-15

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013) Press Release: CDC provides estimate of Americans diagnosed with Lyme disease each year. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2013/p0819-lyme-disease.html

Cook MJ, Puri BK (2016) Commercial test kits for detection of Lyme borreliosis: a meta-analysis of test accuracy. Int’l Journal of General Medicine. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJGM.S122313

Coughlin J, et al. (2018) Imaging glial activation in patients with post-treatment Lyme disease symptoms: a pilot study using [11C]DPA-713 PET. Journal of Neuroinflammation. 201815:346 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-018-1381-4

Embers ME, Barthold SW, Borda JT, Bowers L, Doyle L, Hodzic E, Jacobs MB, Hasenkampf NR, Martin DS, Narasimhan S, Phillippi-Falkenstein KM, Purcell JE, Ratterree MS, Philipp MT. (2012) Persistence of Borrelia burgdorferi in rhesus macaques following antibiotic treatment of disseminated infection. PLoS One 7(1):e29914, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0029914

Fallon BA,et al. (2008) A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of repeated iv antibiotic therapy for Lyme encephalopathy. Neurology 2008, 70, 992–1003. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1212/01.WNL.0000284604.61160.2d

Feng J, Auwaerter PG, Zhang Y. (2015) Drug combinations against Borrelia burgdorferi persisters in vitro: eradication achieved by using daptomycin, cefoperazone and doxycycline. PLoS One 10(3):e0117207, 2015a. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117207

Feng, J, Li T, Yee R, Yuan Y, Bai C, Cai M, Shi W, Embers M, Brayton C, Saeki H, Gabrielson K, Zhang Y. (2019) Stationary Phase Persister/Biofilm Microcolony of Borrelia burgdorferi Causes More Severe Disease in a Mouse Model of Lyme Arthritis: Implications for Understanding Persistence, Post-Treatment Lyme Disease Syndrome (PTLDS), and Treatment Failure. Discov Med 27(148):125-138. http://www.discoverymedicine.com/Jie-Feng/2019/03/persister-biofilm-microcolony-borrelia-burgdorferi-causes-severe-lyme-arthritis-in-mouse-model/

Goswami ND, et al. (2013) The state of infectious diseases clinical trials: A systematic review of clinicaltrials.Gov. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e77086. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077086

Johnson L, et al (2014) Severity of chronic Lyme disease compared to other chronic conditions: a quality of life survey. PeerJ, 2014. 2, e322 DOI: 10.7717/peerj.322.

Johnson, Lorraine (2019): 2019 Chart Book — MyLymeData Registry. (Phase 1 April 27, 2017. Sample 3,903). figshare. Preprint. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.7849244

Moutailler S, et al, (2016) Co-infection of Ticks: The Rule Rather Than the Exception.

PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016 Mar; 10(3): e0004539. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004539

Novak P, Felsenstein D, Mao C, Octavien NR, Zubcevik N (2019) Association of small fiber neuropathy and post treatment Lyme disease syndrome. PLoS ONE 14(2): e0212222. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212222

Rosenberg R, Lindsey NP, et al. (2018) CDC: MMWR. Vital Signs: Trends in Reported Vectorborne Disease Cases — United States and Territories, 2004–2016. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/67/wr/mm6717e1.htm?s

Schwartz A., Hinckley A., Mead P. et al., (2017) Surveillance for Lyme disease, United States, 2008 – 2015. MMWR Surveill Summ. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6622a1

Tick-Borne Disease Working Group 2018 Report to Congress. Available online: https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/tbdwg-report-to-congress-2018.pdf

Tick-Borne Disease Working Group 2018 Sub-Committee Reports. Available online: https://www.hhs.gov/ash/advisory-committees/tickbornedisease/reports/index.html

We invite you to comment on our Facebook page.

Visit LymeDisease.org Facebook Page